This article draws heavily on materials collected by Clare Spicer. With thanks also to Jillian Tretheway and Mike Searle.

Thomas Hutchings was a stone mason, builder, architect and surveyor. He had a major impact on the built heritage of Bridgwater, repairing, building or designing some of the town’s notable landmarks.

Thomas Hutchings was born about 1781. The 1851 census described his birthplace as ‘Kyenton’, although this was in fact Kingston St Mary, near Taunton. Thomas’s baptism is recorded in Kingstone, on 20th May 1781, the only parent given in the ledger being his mother – Mary Hutchings. No comment was made on Mary’s status, although it appears she was an unmarried mother. She was the daughter of John and Thomazin Hutchings, who had been was baptised in Kingstone in 1762. When Thomas was baptised in 1781, there were three baptisms in Kingstone with only the mother’s name given, and no indication as to any of the mothers’ marital status.

On 20 February 1792 an indenture was drawn up by the churchwardens and overseers of the poor of the Parish of Kingston where they placed Thomas Hutchings, aged nine years, ‘a poor child’ of the parish, in apprenticeship to George Bryant the younger, where Thomas would remain until he was twenty one. A memorandum on the back of the document ‘examined the register for Thomas Hutching and now find him to be eleven years of age in May 1792 (Somerset Heritage Centre, D/P/kstone/13/6/10). The inference from this would be that Thomas, being the child of a single mother, was supported by the parish, and they were apprenticing him to Bryant. This would give Bryant a young helper to train up, but also remove Thomas from being a burden on the parish revenues. Unfortunately the document makes no mention of Bryant’s occupation. More information on Bryant’s has yet been found, but given Thomas’ later career, we might assume he was a stone mason.

Thomas would have learnt the basics of construction, essentially stone and bricklaying, but also more intricate work in cutting and shaping stone. There would have also been some element of planning, in laying out foundations and rooms.

By the time he was twenty years old, Thomas was living in Taunton (presumably where Bryant was based), as he married Mary Firze at St James’ Church on 1 February 1801. Banns had been read on 4, 11 and 19 January. Thomas was a resident of the parish of St Mary Magdalen Taunton, while Mary was a resident of St James’. Thomas was able to write his name, although Mary could only make her mark with an ‘x’. Their witnesses were William Shaddick and Joseph Holland.

Thomas and Mary had a daughter that year, Charlotte, who was baptised in 28 June, St Mary Taunton, indicating that Mary had been pregnant at the time of their marriage. This perhaps explains why Thomas was able to marry before the end of his apprenticeship.

Thomas later recalled moving to Bridgwater in 1802. This would have been the year his apprenticeship with Bryant was completed. By 1806 he either established or – more likely – took over a marble mason’s business in North Street. This business would have involved sourcing marble, then either carving it directly to shape, or working up part-finished pieces. Some of the work, for example, would have been carving inscriptions onto already made memorial tablets. Thomas may have been responsible for a number of marble memorial tablets erected on the walls inside St Mary’s Church. He would also have worked better quality stones, such as the prestigious Bath Stone, or traditional yellow Ham Stone. He would also have bought in or made fine marble chimney pieces. We learn from Thomas’ will that the yard was located next to his home, later known as ‘College House’.

After Thomas and Mary’s move to Bridgwater, they had a second daughter, Eliza. She was born about 1804 and was baptised in St Mary’s Church on 23 February 1806.

It is in 1815 that we first learn of Thomas taking on projects as the principle builder. Parker’s Ancient History of Bridgwater (1877, p.37) records:

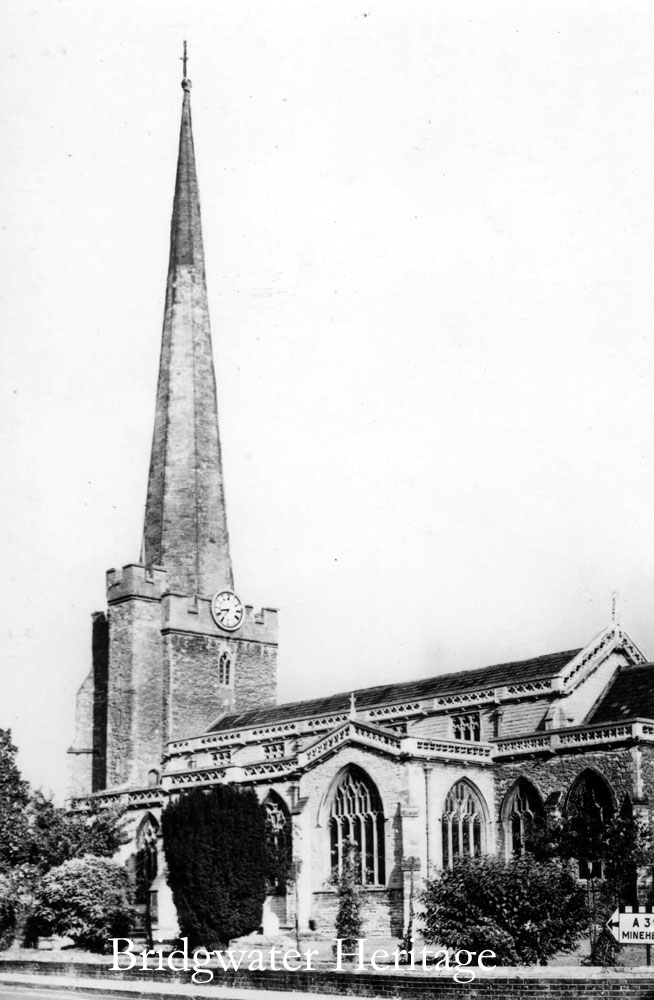

There was an awful thunderstorm in the year 1814, when the church spire was split by lightning. It was so terrific that everyone rushed out of doors expecting to hear of some accident. In the following year it was determined to take down a certain portion of the spire and rebuild it. Of course it was a difficult undertaking. By the advice of a nautical man an ingenious method was at length agreed on. Poles were hoisted to the top of the tower, and two of them lashed with strong ropes round the base of the steeple. Iron rings were riveted large enough to admit the ends of other poles, which where also lashed. Rope ladders were then fastened from pole to pole, as you would mount the rigging of a vessel, so the work was continued until the top of the steeple was attained. Of course a concourse of people gathered to watch a celebrated pilot, named Gover, who fearlessly mounted and brought down the weathercock. The repair of the steeple was undertaken, and well executed, by Mr. Thomas Hutchings, stonemason, and, fortunately, no accident of a serious nature occurred. I remember putting on a sailor’s jacket and mounting one fine afternoon, when the work was three parts finished. A workman took my hand, and I went on a stage which stood inside ; the beautiful view of the surrounding neighbourhood repaid the hazard of the undertaking.’

Thomas was presumably responsible for organising the whole project, including the nautical expert and Gover the fearless clamberer.

The experience at St Mary’s landed Thomas another spire repair, that of St Nicolas in Bristol. He had clearly learned a few tricks from Gover, as the Taunton Courier and Wester Advertiser of 24 October 1816 recalled:

EXTRAORDINARY FEAT.—Saturday se’nnight a young man ascended the lofty steeple of St. Nicholas church, Bristol, for the purpose of taking down the weathercock, to repair its defects. The simplicity of the scaffolding which he made use of, excited universal admiration. It consisted of two poles, carried out from two of the apertures about midway up the steeple, across which two planks were laid, and from thence he ascended bps ladder confined to the steeple by spiral ropes. The most perilous part of the performance was a leap which he was actually obliged to make, from the step of the ladder, to catch hold of the iron cross. Had he failed! – but the idea is too horrid for contemplation. He succeeded, however: and then seated himself astride, took off the cock, which he waved over his head in triumph two or three times, and then descended with his prize. We hear that his charge for this arduous undertaking will not amount to one third of the sum required by eminent master builders previously consulted. He is the same young man who performed much useful and important work on the steeple at Bridgwater.—The new weathercock was put up on Wednesday last, in the presence of immense crowds of spectators. It weighs 33lbs. The name of the young man employed upon this occasion is Hutchings, marble mason, of Bridgwater, He has offered to ascend the steeple again, without either scaffolding at ladder!

The next major project we know Hutchings was engaged in (although there we no doubt countless more in between) was the building of the dome of the Cornhill in 1826 to 1827. The architect was Richard Carver, who was a prolific Somerset architect, who also designed Holy Trinity in Bridgwater (1839, which Thomas would later work on), the Courthouse in Queen Street (1859), the Gaol in Fore Street (1832) and others. Carver favoured working in Bath Stone, and it is likely Hutchings was favoured for some of these contracts due to his apparent specialism in stone. However, the Cornhill project, despite being Bridgwater’s premier landmark was not necessarily a happy project. The Bath Stone selected was apparently of poor quality, resulting in the need for regular resurfacing work (Lawrence, History of Bridgwater, 150). Whether this was Carver or Hutching’s fault is unclear. Regardless of the technical problems, the Cornhill itself is a fine building, and something Thomas should be better remembered for.

In April 1828 we get our first indication that Thomas was a non-conformist when it came to religion. He is mentioned (occupation given as mason) in the deeds for the Pedwell Methodist Chapel, along with others, including John Snook of Bridgwater, druggist (who appears below – Somerset Heritage Centre D/N/bmc/2/1/10).

Hutchings work on the Cornhill no doubt gave him some good contact with Bridgwater’s Town Council. In February 1829 the council resolved to rebuild the quayside on the south east side of the town bridge, which until recently had been occupied by a cluster of houses and yards. Thomas was awarded the contract to take down the existing brick quayside and build a new lias stone slipway and quay wall. He was to level up the ground behind, provide an ornamental water pump (for the use of the ships and nearby houses), along with iron railings. The Council Minute notes of May 1829 record Hutchings having executed his contract (with thanks to Mike Searle for passing on these details).

In 1831 Thomas and Mary saw the marriage of their second daughter Eliza to Richard Auger, an excise officer of Bridgwater, indicating the growing prosperity of the family.

With the apparent success of his building business, Thomas now seems to have given up the marble retail side of his work. His recent projects had utilised his expertise in stone carving, but with much more emphasis on building rather than decorative marble. As such, in the Sherborne Mercury of 6 June 1831:

TO STATUARY AND MARBLE MASONS. TO BE DISPOSED OF, And entered upon immediately, THAT long-established Yard, Work-Shops, and newly-erected Show-Room, situate in North Steet Bridgwater, Somerset, where a considerable business has been carried on for the last twenty-five years, by Mr. Thomas Hutchings, who is now about to decline. The Stock consists of statuary, vein, and a variety of other Marble, together with Portland, Bath, and other Stone; also several modern and elegantly designed marble Chimney Pieces. For further particulars apply, if by letter, post paid to Mr T. Hutchings, Bridgwater.

In Robson’s 1839 directory Thomas was listed as a ‘Builder’ in North Street, and under a separate heading was S. Herford/Hurford a marble and stone mason, also of North Street. At that time there were no other builders or masons listed in North Street, so it looks as though Samuel Herford bought the business from Thomas. Another look at the 1841 and 1851 census reveals S. Herford living right next door to Thomas Hutchings, so we can perhaps be confident that Herford took on the business. The business was presumably later passed to Charles Green, memorial mason of North Street, who lived across the road from the yard, in number 15 North Street.

Electoral roll evidence indicates that in 1832, 1834 and 1846 Thomas had houses in Penel Orlieu and Ropers Lane (Albert Street), which were occupied by tenants. These were ‘courts’, essentially rows or clusters of small terraces built behind the main street around a narrow ‘drang’ or courtyard. These houses would not have their own garden or toilet. Much of the West Street, Albert Street and Northgate area, which in the eighteenth century were primarily cottage garden plots, was redeveloped in this way.

On the 1889 25” OS map a row of eight cottages adjoining the Wesleyan burial ground are called ‘Hutching’s Row’. Unlike the courts of this area, these cottages seem to have their own garden spaces, albeit small ones. However, these gardens were accessed communally, and there seems to be a shared privy. The burial ground had been laid out in about 1830, although the land wasn’t purchased by the congregation until 1835. The ground on which Hutchings Row was built had been owned by Henry Harvey (descendant of the Harveys of Bridgwater Castle) who sold the land to Snook between May 1828 and March 1833. The property at the time was a single dwelling house, with garden adjoining. On 25 August 1833 Snook sold the land to Hutchings, although Hutchings could not afford the sum of £270 up front, so the land would be rented for £13 20s annually until Hutchings paid the full amount (which he never did). Snook promptly sold this rent to John Webber Jones of North Petherton for £230. Interestingly, in the document where Snook sold to Hutchings there is already a mention of ‘eight messuages or dwelling houses adjoining to the aforesaid messuage or dwelling house and already erected and built by the said Thomas Hutchings on the aforesaid Garden Ground’. At this time Thomas was described as a stone mason. (Somerset Heritage Centre DD/LO/13/2).

In 1834 Thomas pitched for the contract to build the town’s new Union Workhouse at Northgate. He was competing against Pollard & Son, and J.W. Wainwright of Taunton; the latter would win the competition. It was probably around this time that Thomas’ wife Mary died. It’s unclear the circumstances around her death, we only know when Thomas remarried at the end of 1835 he was described as widower. Mary does not appear in the burial registers of St Mary’s church. We know that Thomas was probably a Wesleyan by this time, and he would be buried in their burial ground in Albert Street. However, Mary does not appear in the burial grounds of that ground, although there is a gap in the records for 1834-1840 in which she might have been missed. Otherwise she may have been returned to a family plot in Taunton.

On 23 December 1835 Thomas married by licence Betsy Boulting in St Mary’s Church, Bridgwater. Both were described ‘of this parish’. Both could sign their names. Witnesses were James Whitworth and Mary Ann Boulting. We have a snapshot of their family home in the 1841 census for North Street Bridgwater. We find Thomas, builder, Betsy, then living with them is 38-year-old Eliza Auger, ‘assistant’ and 8-year-old Richard Auger. Their home is almost certainly ‘College House’ (as it would later be called), which Thomas had built. Eliza Auger was Thomas’ second daughter from his marriage to Mary. Richard was Eliza’s son. Eliza’s husband, Richard Auger, had died in 1832. Eliza remarried in September that year to a William Sherrin. They moved to Milverton by 1851, then back to Bridgwater by 1861. She died in 1893.

In the 1835 Borough property report, we a couple of mentions of Thomas.

He owned land on the east side of North Street, ‘Hutching’s Land’ which abutted on its south side a piece of council land, which was leased by John Jeffrey in 1800, but occupied in 1835 by Thomas Hutchings. Although Thomas was in occupation of both, there was a covenant on the council land that he could not remove the boundary wall between them. We might read this as being the land for College House in the north, and the land for the marble yard to the south.

He owned a garden in King Square which adjoined a small property he leased from the Council fronting Northgate. He had taken the lease in 1830 (which appears in the Council Minutes – with thanks to Mike Searle for the reference), and by 1835 Thomas had built a school house there, which also ran into the adjoining plot on the east. The significance of this schoolhouse is unknown. It may have been associated with the Wesleyans. The portion on Thomas’ plot is possibly the modest building still standing there, albeit heavily altered.

The garden plot in King Square Thomas would develop in 1850, building a grand town house in the style of the houses in the square already built. He presumably built the adjoining house to the west, which matches. On the side of his own he left a line of alternating protruding bricks, anticipating the building of more next door. However the building of the Masonic Chapel several decades later prevented this happening. It is interesting to note that Thomas did not own this building when he died, or even continued the project. Presumably building high-end dwellings did not prove a profitable venture, hence we find Thomas concentrating more on working-class housing.

In 1839 we get another glimpse into Thomas’ housing developments. That year was the shocking murder in one of the groups of houses called ‘Hutchings Buildings’ in North Street. William Hayward, an 18/19 year old and son of a local gardener, insulted and hit the daughter of John MacCarthy, an Irish-born portrait painter who lived in Hutchings Buildings. MacCarthy, with his son and son-in-law went into the courtyard and confronted Hayward, who threatened the three of them, passed through the court’s ‘drangway’ into North Street, three off his coat and got into a fight with MacCarthy’s son, before John could hold his son back. Hayward proceeded to strike young MacCarthy to death with a pointed stone (Leamington Spa Courier, 26 January 1839). Hayward was sentenced to transportation for life, presumably to Australia (Exeter and Plymouth Gazette 13 April 1839) We see two such ‘Hutchings Buildings’ on the 1887 OS 25” Town Plan, one stretching between Penel Orlieu and Mount Street, the other behind College House in North Street. The murder presumably occurred in the latter, although that row of cottages was accessed via Mount Street in 1887. The 1854 Town Plan shows eight cottages (combined down to five in 1887) and no sign of access at the back, so it could be they were accessed via North Street at this time and this was later sealed off. It is interesting to note an artisan like MacCarthy living in these court cottages, perhaps indicating that in the early years these sorts of cottages were a little more prestigious than they were later known for.

In Robson’s Directory for 1839 Thomas described himself as ‘Architect and surveyor, builder and undertaker.’ It seems odd for Thomas to mention undertaking here. It may be that the trade in building brick vaults in burial grounds and memorial structures in cemeteries had provided the opportunity for commercial diversification, or it may be that ‘undertaker’ has a more broad meaning here, as someone who undertakes to do a job and subcontracts, perhaps in the sense of a modern site manager.

Pictures of the long terraces built nearby the two Hutchings Buildings, especially that seen in an interwar aerial photograph, show a fairly uniform style to most of the terraces. Although we can only be confident that Thomas built five such court terraces (see below – two in Penel Orlieu, two in North Street and one in Albert Street), it is tempting to wonder whether Thomas was responsible for building others as work for other people. There is a suggestive correlation between court building and Thomas’ lifespan, after which emphasis turned to more conventional new streets, such as those around St John Street. However, we will probably never know how many Thomas was responsible for building; court architecture was such they would by nature look uniform, and any competent bricklayer might have been able to throw some of these buildings up. Thomas would have had more capital and expertise to plan and execute than some of the simpler courts found around the town. More work on this area needs to be done.

In terms of more prestigious work, in 1839 Thomas built Holy Trinity Church on Taunton Road. This was to a design by Richard Carver. We know this as inn 1939 Thomas Hutchings was remembered by a husband of one of his granddaughters as builder of Holy Trinity Church (Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser 29 July 1939).

On 5 April 1839, Thomas’ eldest daughter Charlotte was married to widower Richard Preece, a cheese dealer of Bridgwater. They set up home in Friarn Street, although Richard would die in 1845. They had three children – two daughters- Almah 1841 and Sarah 1842, and a boy, Richard Hutchings Preece, who only lived a short time – 1843-1844. She then moved to Clare Street with her daughter Sarah by 1851, then by 1861 she was living with her other daughter’s (Alina’s) family in St Mary Street, Sarah having married William Cooper a woollen draper. She died in 1872.

At a Vestry Meeting of February 1848 Thomas was listed as part of a committee engaged with looking in to the state of St Mary’s Churchyard and a scheme to start a new cemetery (which would ultimately result in the Wembdon Road). Thomas was presumably helping with surveying and costing such a project. He also carried out some other work on or within St Mary’s church, possibly reordering the pews, or some other alteration, as a Vestry Meeting that August discussed his bill: he had claimed over £50 to supervise work costing about £180, and was accused of ‘sharp practice’. Despite this, in August 1853 Thomas was again hired to make repairs to the church, although he does not seem to have been involved with the major restoration undertaken by Brakespear.

In the 1851 census Thomas, aged 70, described himself as an ‘Architect and Builder’. Betsy, now 65, was ‘architect’s wife’. Living with them was Mary Ann Boulting, aged 55 Annuitant (presumably Betsy’s sister), grandson Richard A Auger, aged 19 at school and Ann Bishop, 24-year-old servant. Thomas probably had no architectural qualification, but he presumably described himself as such due to his confidence at surveying and planning certainly building types, not least housing. He was probably competent at drawing up detailed ground plans, but whether he went as far as designing elevations is unclear, and possibly unlikely.

That year would see a horrific incident in the Hutchings household. Wells Journal 27 December 1851:

SUICIDE. On Thursday morning, the wife of Mr. Thomas Hutchings, North-street, committed suicide by cuttings her throat in a most shocking manner. It appeals that for some time past, the deceased has been suffering under slight mental derangement. On Thursday morning at half-past nine o clock she had not risen from her bed. The family were at prayers after breakfast in the parlours, when on a sudden they were startled by hearing something fall heavily on the floor upstairs, and after the prayers were concluded, some one hastened to discover what it was. On entering Mrs. Hutchings’s bedroom, the unfortunate woman was found on her knees leaning on the night commode, with her throat so lacerated as almost to sever the head from the body. Life was quite extinct. A razor, was found near, with which she had committed the fearful act. During the course of the same morning a coroner’s inquest was held on the body before Evered Poole, Esq., the borough coroner, when a verdict was returned of ” Temporary Insanity.”

Betsy Hutchings buried in the Wesleyan burial ground on 24 December 1851. It is notable that Thomas would be buried with her when he later died, even though he had remarried by that point.

Thomas would marry for a third time in the third quarter 1852. This was to an Anna Batten, a widow of a master baker in Taunton called Henry Batten, who had died the year before. Her maiden name was Lock or Locke, and she put her birthplace as Hillfarrance in Somerset, in 1811. There is a legal civil registration of their marriage in Taunton (Quarter Jul-Sep, Vol 5c, Page 605). It is possible they got married in the Registry Office there.

In 1856 Thomas was awarded the contract to build the Dissenter Chapel in the Wembdon Road cemetery, which had been designed by Mr Robert Down of Bridgwater. It was a relatively simple gothic box, but had a series of burial vaults below the floor.

In 1857 Thomas was on a committee of the Wesleyan chapel in relation to drawing up new rules for the burial ground in Albert Street. One of the rules brought in was that only members of the congregation should be buried there. Thomas was a committed member of that congregation, and in 1860 designed and surveyed modifications to the building, including raising the roof, adding a new portico along with a manse for the minister in Dampiet Street. He was credited as architect and surveyor, while Mr Kitch was the builder. Thomas had done this work for free, and had donated towards the building work. At the ceremony on the laying of the foundation stone he said the following:

Mr Hutchings stated that it was 58 years since he came into Bridgwater, and he thought he might safely say that the prosperity of the various sections of the Christian Church had been such that where there was then one worshipper there were now one hundred. Since he had been in the town he had seen women as well as men standing up to their knees in mud, fighting, and tearing each other’s hair. He did not see such things now. He remembered the commencement of the Wesleyan Chapel, and had attended the openings of most of the chapels in the town and neighbourhood. Great Christian progress had been made through the mercy of God, and though he was now eighty years of age he hoped to see the good work prosper yet more abundantly. One member of his family was 108 years of age (laughter and applause). He was deeply gratified at being enabled to witness and take part in, the ceremony that day’. (Bridgwater Mercury, 5 July 1860).

In 1859 Thomas drew up plans for the rebuilding of the Market House Inn, a medieval building once known as the Valiant Soldier. The Turnpike Trustees wanted to widen the road here. It is unclear if Thomas also carried out the building work, or just devised the scheme. He designed an elegant curved building, which incorporated some of the old building behind (including a substantial fireplace), and kept as a centre piece an old doorway with datestone of 1561 (Bridgwater Mercury 9 February and 9 March 1859).

In the 1861 census we find in North Street Anna Hutchings, aged 50 ‘surveyor’s wife’, indicating that Thomas was away at the time. Living there was a 16 year old Betsy H. Sherrin, Thomas’ granddaughter, who worked as a milliner, and Mary A Bale, 19 year old servant. Betsy Sherrin was a daughter of Thomas’ daughter from his first wife.

In 1863, aged about 82, Thomas was still undertaking building projects. He drew up his will this year, and in it he mentions lands on the west of North Street on which he was in the process of building six cottages. The only set of buildings that fits this description would be ‘North Street Terrace’, which is a row of five cottages with another detached on the same plot. Another possibility might be Southbourne Terrace, although that extended to ten cottages, and a later amendment to the will does not mention that the number of cottages might have changed.

The first executor was named as William Lock of Taunton, baker and confectioner, and Thomas’ nephew. The second man named as trustee in the will was Robert Bate, ‘gentleman’. From census records, he was born in Cornwall but lived in Bridgwater for a long time. In 1841 and 1851 he seemed to describe himself as a ‘conveyancer’, nowadays the term refers to someone involved in property transactions, and that would be a good business fit for Thomas’s building work. By 1861 he was described as a magistrate of Bridgwater, but he died on 25 September 1867 so before Thomas Hutchings.

In December 1863 there were fears the gallery in Holy Trinity Church was in danger of collapsing. Thomas surveyed the building and discovered that the side walls were no longer on the perpendicular. He recommended iron bars be run through the church to pull it back into shape. Although his recommendations were questioned, this report seems to confirm that Thomas was the original builder (Bridgwater Mercury 1 December 1863).

Thomas Hutchings died on 23 September 1868. He was buried two days later in the old Wesleyan Burial Ground in Albert Street, in the same grave as his second wife Betsy. In the 1870s he was remembered as a ‘surveyor of Bridgwater’ (Cardiff Times 05 December 1874).

In his will, drawn up on 1 February 1863, Thomas left the following properties:

- Six dwellings in Great Alfred Street, Weston super Mare (now just Alfred Street). It is unclear where these are, but almost certainly among the older southern end of the street.

- A dwelling known as the ‘Weston super Mare Terminus Tavern’ and a dwelling adjoining

- His dwelling house in North Street, Bridgwater, with 8 adjoining cottages and a further stone mason’s yard also adjoining. These would presumably have been completed by the time of his death.

- Sixteen dwellings in Pig market (Penel Orlieu) and Pricket’s Lane (Market Street). We can maybe assume these straddle the join of Penel Orlieu and Market Street and is probably Somerset Place.

- Nine cottages in Pig Cross / Penel Orlieu. This is most likely Hutching’s Buildings.

- Eight Cottages in Albert Street. These will be Hutching’s Row.

- Three Dwellings in High Street ‘lately purchased of Jane Williams’

POSTSCRIPT

Anna continued to live in Bridgwater, and by 1881 had moved to 2 Alexandra Villas. She lived on income from the properties Thomas had left her. Anna seemed to have leaned more to the Anglican Church than Thomas, but she may have changed in that direction after he had died. She died in 1890 at Weston super Mare, and was buried in the Wembdon Road Cemetery, Church of England side, in the plot of her son from her first marriage, Henry William Batten. When she died she still retained some of Thomas’ property with some additions of her own:

- A dwelling house and shop on the Cornhill (lately occupied by her son Henry William Batten, now occupied by Mr Oliver)

- Eight Houses and gardens on the Mount (most likely Hutchings Buildings already mentioned)

- Six dwellings in Alfred Street, Weston Super Mare

- A house in Railway Parade, Weston Super Mare

- A House in Orchard Street, Weston Super Mare

OTHER BUILDINGS

Thomas also built the National Provincial Bank on the Cornhill. This building was later re-built in a renaissance style and would become NatWest.

Miles Kerr-Peterson 1 June 2023