The King James Grammar School is one of Bridgwater’s lost institutions. It had promising beginnings, but ultimately failed in the late nineteenth century.

Foundation

Bridgwater probably had a school from its foundation in 1200, and certainly had one by 1298, which was associated the Hospital of St John in Eastover. The hospital supported the free education of 13 boys, and more would have been privately funded by the wealthy townsmen. In the 1530s the Hospital was suppressed by Henry VIII, although part of its endowment was set aside for continue educating 13 boys. However, the removing of the monastic underpinning of the town’s school led the Corporation (Town Council) in 1548 petitioning the Crown for a grammar school. This would provide a legal framework for the institution and an endowment of land to support the schoolmaster. Thirteen years later the Corporation was granted its wish by the new government of Queen Elizabeth. The 1561 foundation provided for six nominated boys to be educated for free by the school. The schoolmaster could then take on as many fee-paying pupils as he liked.

A full list of masters has not yet been compiled, although most of the 19th century ones are traced below.

Henry Attwood was one of the early masters of the Grammar School, and taught Robert Blake in the 1610s.

In 1612 King James confirmed Elizabeth’s previous grant, and thereafter the school became known as the King James Grammar School, or King James’ School.[1] This was a Church of England boys’ grammar school, separate from the later and better-known Dr Morgan’s School. The Grammar School was intended for the sons of well-to-do farmers and merchants, and focused on a classical education: English grammar, Latin, Greek, mathematics, and Bible studies with a view to preparing boys for Oxford and Cambridge. The master of the school would almost always be a clergyman. The master of King James Grammar reported to the Borough of Bridgwater and to the Bishop of Bath and Wells.

By 1650, the school was held in the upper floor of the building now known as the Mansion House, then often referred to as just ‘the school house’.[2]

Samuel Darby, was master of the Grammar School for a time, mentioned in 1703.[3]

In 1751 Stephen Whatley’s description of Bridgwater mentions ‘a large free school… and under it are lodgings for the poor of the parish’.[4] The town was repairing ‘the Free School’ in 1772. However by 1801 the building was described as ‘formerly called the School House and now for many years past called The Mansion House’. This indicates that the school had moved on by then.

Rev. Richard J. R. Jenkins (1737-1809) served as master 1790-1809

[text adapted from Jillian Trethewey and Clare Spicer’s article on Dr Morgan’s, and their research forms the basis of many of the following notes]

Born in Tenby, Wales, Jenkins was son of an excise officer. He studied at Oxford University and was ordained as a deacon in 1786. He married Catherine Crandon at St Mary’s parish church in 1788, so he had some connection with Bridgwater prior to being appointed master of Dr Morgan’s in 1789. Richard focused on teaching reading, writing, arithmetic and religious education. By law, all schoolmasters had to conform to the Church of England faith and the grammar schools preferred schoolmasters to be clergymen with a degree. In the space of three exciting weeks in September and October 1790, Richard was ordained a priest and the Bishop licenced him to be a preacher and reader in Bridgwater. At the same time the new Rev. Jenkins was also appointed master of the King James Grammar School. As the two schools now had the same sole teacher, both may have used the schoolroom in the Church House, at different times. Richard was awarded a B. & D.D. from Oxford in 1808 and resigned from both schools in 1809 to become a curate in Kent. The Borough sold the Mansion House in 1801, as noted above.

Rev. Caleb Rockett, M.A. (1766–1837), served as master 1810–1819

Caleb Rockett was born in 1766 and was the son of Caleb Rockett of Honiton in Devon. He matriculated from Balliol College Oxford on 9 May 1785 aged 19 and achieved a BA from Exeter College in 1791. At the end of that year he was admitted to the Freemasons Lodge of Unity in Ilminster. He was described as ‘clergyman of Ilminster’.

By 1801 he was teaching, and advertised in that his school in Dartmouth Devon would charge £30 per year.[5] On 20 August 1802 Caleb (described as ‘of Townshall Devon’) married Agnes Bullen of Nether Stowey, by licence. Both Caleb and Agnes were able to sign their names.[6]

While teaching in Townstal he was also keeping up his own education, and was awarded an M.A. from Jesus College Cambridge in 1803. In 1804, the Exeter Flying Post of 2 February mentioned that Caleb was chaplain to the Lord Bishop of Bath and Wells and vicar of Stokenham, and was being instituted to the vicarage of Townstal, Dartmouth.

He was made a prebendary of Wells in 1807, then vicar of Westonzoyland in 1808. This appointment shifted Caleb’s focus from Devon to Somerset. Two years later he was appointed master of the King James Grammar School.

Even though he had moved away from Devon, in 1810 his old parish of St Saviour’s in Dartmouth were keen to honour their old vicar with a handsome piece of plate (silver), value 60 guineas, ‘as a mark of their esteem and approbation of his conduct during a period of 18 years, when he officiated as the minister of the church of in that town’ (Hereford Journal, 20 June 1810)

Now in position in Bridgwater, in August 1810 Rev C. Rockett put 60 acres of meadow land, pasture and arable land in Westonzoyland for rent Land for Rent. These were presumably lands associated with the parish that paid for his stipend. Sad news arrived in October 1811, as Caleb’s brother Joshua, deputy inspector of hospitals for the Western District, killed himself.

We have little record of Caleb’s running of the school in this period, beside occasional mentions of the school’s term times in the local press, such as on 19 December 1816 when the Taunton Courier mentions that the Bridgwater Grammar School, Mr Rockett advertised that the Christmas Vacation will commence on 18 December and will finish 27 January.

Caleb was also made vicar of East Brent from 1819, which he held until his death on 9 June 1837. With this new position he gave up the running of the Grammar School by the end of the year. On 27 May 1819 a meeting of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge held their anniversary meeting at Bridgwater, which followed by a sermon by Caleb Rockett, described as ‘lecturer of Bridgwater and vicar of East Brent and Weston Zoyland’.

Thereafter Caleb’s seems to have led a relatively quiet life as a country vicar. In 1834 he was registered to vote in Bridgwater as he owned a house in King Square, although his place of abode was marked as East Brent. It may be he rented the King Square house to his successors in the Grammar School. Caleb died on 16 June 1837, aged 71 and was buried in the churchyard of East Brent.

Caleb and Agnes had at least two children. Elizabeth, their only daughter, who died 18 December 1847, and Rev. Caleb Rockett the younger, who died 1 December 1849.

Rev. John Dawes M.A., (c.1778-1838), served as master 1819-1826.

On 8 July 1811 Rev. John Dawes married by licence at Stogursey a Mary Coombe. Other marriages performed around that time in the parish tell us that John was a curate there, and the birth of his children Thomas, Elizabeth and Richard indicate they remained in the parish for the next 8 years.

On 1 August 1819, the Taunton Courier reported that the Rev. J. Dawes was about to be nominated by the Bishop of Bath and Wells to the mastership of the Grammar School of Bridgwater, since Rev. C. Rockett had resigned. The school would charge 24 guineas for board for boys under ten, 26 guineas for boys under 14; 6 guineas for classical tuition in writing and arithmetic and 2 more guineas for laundry. Day boys were also taken. Additional masters taught French, Dancing and Drawing specifically. The school was due to reopen on 26 July. A particular perk of the school noted on was that ‘each pupil will have a separate bed’.

As well as being master of the School, over June and July of 1823 Dawes was secretary for the forming Bridgwater district committee of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. Daves moved on by 1826, probably having taken up a position in Taunton: on 29 December 1825 Mary died in Bridgwater, and was buried in Westonzoyland. John was described at the time as master of the grammar school in Taunton in the death notices.[7] John died in Bridgwater on 19 April 1838, described as ‘formerly master of the Grammar School of that town’.[8] He was buried with Mary in Westonzoyland.

Rev. James Henshaw Gregg, B.A., (1802-1834) served as master 1826-c.1832

Rev. James Henshaw Gregg B.A. (1802-1834), from London, was appointed master in March 1826 and was ordained the following year. On 8 August 1831 he applied for a licence to marry Jane Woolen of Edington in the church of Moorlinch. He was vicar of Durleigh until his death on 29 October 1834 and is buried in St Mary’s churchyard, Bridgwater. His death notices refer to him being master of the grammar school, but that seems at odds with the presence of Mr Giles in 1832.

?Mr Giles c.1832

Little is known about this individual.In 1832 the Bridgwater Alfred of 11 June gave a detailed description of the annual examination of the young gentlemen of the Grammar School in King Square. This was conducted by Mr Giles ‘himself’ and assisted by a Mr Griffith. There was an audience of the youngsters friends and parents, along with local clergy and gentry. The examination took the form of a spoken question and answer session on the history, doctrines and philosophies of the New Testament, then on Greek (specifically Contra Thebas of Aeschylus and Anabasis of Xenophon), Latin (Virgil’s Aeneid) and French language (Le Lecteur Francais), then history (based on Robertson’s conquest of South America by the Spanish) and mathematics (mostly Algebra and Calculus). It could be this was just visiting to conduct the exams, although the ‘himself’ might imply he was the master. Of nothing else this confirms the location of the school in King Square, the first confirmed siting of it since the Mansion House.

Rev. Thomas Gilbert Griffith, B.A. (c1797-1855) served as master 1835-1837

Rev. Thomas Gilbert Griffith B.A. (c1797-1855) was from London. He is probably the assistant to Mr Giles mentioned above in 1832. In 1835 he was licenced by the Bishop of Bath and Wells as Master of the school.[9] He moved on my 1837.

Rev. Todd Thomas Jones, M.A. (c1806-1854) served as master 1837–1839

Rev. Todd Thomas Jones M.A. from Exeter was appointed in 1837 but soon left in 1839 following conflict with the Trustees of Bridgwater’s charities. He became vicar of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. The dispute was because Jones had declined to enrol four boys recommended by the Trustees and so had lost the confidence of them. The trustees included a number of Dissenters (non-Church of England), and so Jones did not recognise their authority. Whether Rev. Jones was acting on the instruction of the vicar or even the bishop is not known.

Trustees of Municipal Charities were required to submit written reports to the Lord Chancellor and so in December 1838 they described the King James Grammar School, here called the ‘Classical School’ in the following terms:

The Rev. T. D. Jones has been appointed, by the Bishop of the diocese, master of the Classical School, and, immediately on the trustees being informed of his appointment, they nominated four young gentlemen, namely, F. T. Heard, W. R. Granger, C. Gillard, and G. J. Woodward, as pupils, but Mr. Jones having thought fit to question the authority of the trustees, and having refused to admit the young gentlemen as their nominees, the trustees have not any report to make respecting them.

Julius Miles, B.A. (1811-1894) served as master 1840 to 1845-.

Julius Miles B.A.was from Cambridge. He attended St John’s College Cambridge. He had been ‘assistant in a seminary kept by Mr Barnes of Dorchester’ and then assistant to the school master of Bridgwater.[10] He had married Mary Durden in Dorchester on 10 June 1839. He was appointed as master of Bridgwater by the bishop of Bath and Wells in March 1840.[11] By July he was advertising the following:

THE BRIDGWATER FREE GRAMMAR SCHOOL

(Founded by King James the First.)

Conducted by Mr. JULIUS MILES.In this Establishment young Gentlemen may be conducted through a course of Classic Authors, or Pure Mathematics, for either of the Universities of Cambridge and Oxford, or be forwarded in Navigation, Surveying, and Trigonometry, as well as in a routine of English Education, adapted to the pursuits of life.

TERMS—including the Classics, Mathematics, and Washing: 30 Guineas per Annum.

Not including the above: 25 Guineas per Annum.

Parlour Boarders: 50 Guineas per Annum.Young Gentlemen in preparation for Medical Examination forwarded in Celsus and Gregory.

The Premises, which are pleasantly situated in an open and healthy part of the town of Bridgwater, consist of a spacious House, with a very large Play Ground, a capacious, lofty, and well ventilated School Room, and large and comfortable Sleeping Apartments, with every other accommodation and convenience that can promote the health and comfort of the Pupils.

The School RE-OPENS on the 20th of JULY.[12]

In March 1841 he was advertising that he had ‘secured the assistance of a distinguished continental professor of the modern languages [French and German] and other branches of polite education’.[13] In the 1842 census we find Julius and Mary living in George Lane (now George Street). With them with their two children Julius jnr and Louisa; Albert Block, professor of languages (the continental professor); five pupils and a servant. In 1843 he was advertising for an English Assistant.[14]

In August 1845 Julius as pursued in court by Cornelius Parsons, grocer and baker of Bridgwater for £52 in unpaid bills. Julius lost the case and either this or an accumulation of debts forced him out of the job. Julius had left Bridgwater by November 1845, when he was lodging in College Street in Bristol ‘out of business or any profession’ and now bankrupt.[15] In March the following year he was sentenced to six months in prison for his debts.[16]

By the 1851 census the Miles seem to have settled in Clifton in Bristol. Julius was described as a professor of Classics and Mathematics. On 15 July 1858 the Dorst Chronicle recorded the marriage of Julius Miles, formerly Head Master of the Bridgwater Grammar School, to Georgiana, daughter of the late James Cheshire, at Clifton. He continued teaching for the rest of his life.

Rev. Dr Thomas A. Stantial, M.A., D.C.L., (1825-1906) served as master from c.1848 to 1862

Rev. Dr Thomas A. Stantial, M.A., D.C.L. (1848–1862), noted for both scholarship and authoring a widely used “Test-Book” for university and civil service candidates. He was from Corsham in Wiltshire, and was born in 1825. He was master of the grammar school by July 1849, when he marred Eliza White Akerman in Penzance Cornwall.[17] Thomas had studied at St Mary Magdalane Hall, Oxford.[18]

Samuel Lewis’ Description of Bridgwater of 1849 describes the school:

“The free grammar school was founded in 1561, and endowed by Queen Elizabeth with £6. 13. 4. per annum, charged on the tithes of the parish, to which two donations of £100 each were added: it is under the control of the corporation, who appoint the master, and the inspection of the bishop of the diocese; four boys are instructed gratuitously in English and the classics.”

George’s Knight’s description of 1853 has

“The Endowed Free Grammar school was founded in 1561. The master is appointed by the Bishop of Bath and Wells: four boys are taught gratuitously in the classics, and four in the English language.”

In the 1851 census we find his household in Dampiet Street. Living with him and Eliza was their daughter Catherine, an Elizabeth Akerman ‘visitor, widow, annuitant’, five pupils, a cook and a maid. Through the 1850s Thomas picked up additional work through officiating at funerals in the Wembdon Road Cemetery. In 1852 he was appointed assistant curate of Chilton Trinity.[19] That year Thomas was advertising the school, noting that there was a resident French Master.[20]

Eliza died of tuberculosis in February 1853. She was only 31 years old. She was buried in the Wembdon Road Cemetery. The grave inscription reads: “In Memory of Eliza White the beloved wife of Rev. Thos. Stantial who died February 23rd 1853 aged 31 years. Also of Emma her infant daughter.” Eliza’s burial record notes that Thomas had moved the school to Castle Street by this time, and it would remain there until the end of the school’s existence.

Two years later, on 3 July 1855, “Thomas Stantial (son of Christopher Stantial), widower, clerk in holy orders of Castle Street, married Isabelle Poole, also of Castle Street (Father John Evered Poole, attorney at law)”.

Thomas continued to run advertisements for the school in the local press. On 7 July 1859 the Dorset and Somerset Chronicle reported:

‘a few gentlemen’s sons are received as boarders in the Principal’s Family, and an effort is made to combine home influence and comforts with the advantages of a high educational course – there will be one or two vacancies during the ensuing term commending 1 August’.

That year Thomas published A Test-book for Students: Comprising Sets of Examination Papers Upon Language and Literature[21], which was published by Bell and Daldy.

On 27 June 1860, the Taunton Courier reported:

BRIDGWATER GRAMMAR SCHOOL.

The annual examination of the scholars educated at King James’ Grammar School terminated on Tuesday, June 19th, when the viva voce examination took place. The examiners were the venerable Archdeacon Denison, and the Rev. W. C. Lake, M.A., rector of Huntspill, late Senior Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. The subjects of examination were Divinity, the Latin and Greek Classics, with Mathematics and English. The examiners expressed themselves exceedingly satisfied with the general results of the examination, especially commenting upon the marked improvement made during the past year, and warmly commending some boys who had shown particular proficiency. The prizes were awarded as follows:—

GIVEN BY THE TRUSTEES.—1st prize for Classics and Mathematics: Edward Mockridge; 2nd prize for Classics, W. H. Bull; 2nd prize for Mathematics, Burton West.

GIVEN BY THE VICAR OF BRIDGWATER.—Prize for knowledge of the Greek Testament, John Hunter Leversedge.

GIVEN BY THE HEAD MASTER.—Prize for general advancement in the lower division, Philip Thompson.

The 1861 census shows Stantial’s household in Castle Street. Along with his wife Isabella, two children and three servants were three boarding students.

Thomas was still advertising for new pupils in October 1862.[22] However by the end of the year he seems to have suddenly left, leaving a vacancy to be filled by February 1863.[23]

When Thomas died in April 1906, his obituaries summaried his career;

Death of Thomas Stantial, DCL, vicar of St John’s Bury St Edmunds, died suddenly aged 81 years. He had been vicar there 22 years, and before that he was vicar of St John’s Clapham Rise. Headmaster of the Bridgwater Grammar School from 1848 to 1862, then Ramsgate College until 1875.[24]

Rev. Francis Cotton Marshall (1831-1910) served as master 1863-1864

Rev. Francis Cotton Marshall (1831–1910) was a clergyman and schoolmaster. His full biography can be found on the website of the Friends of the Wembdon Road Cemetery by Jill Tretheway and Clare Spicer.

Born in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, he studied at Norwich and Huntingdon Grammar Schools before earning his B.A. from Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, in 1856. He began his teaching career at King William’s College on the Isle of Man, where he met Harriet Brown, the daughter of a vicar. They married in 1863 and moved to Bridgwater, where Francis became the schoolmaster at King James Grammar School and later a curate at Chilton Trinity. Harriet gave birth to their son, Francis Harriet Cotton Marshall, in July 1864 but tragically died of scarlet fever six days later. Francis, now a widower, left Bridgwater, and his family helped raise his son. He continued his clerical career, serving as curate in Grantchester and Cambridge, later becoming Rector of Alvescot and Little Wilbraham. His son studied at Perse School and Clifton College before attending Cambridge. In retirement, Francis moved to Teignmouth with his sister Anna. He passed away in 1910 and was buried alongside Harriet in Wembdon Road Cemetery. Anna remained in Teignmouth until her death in 1926.

Rev. Ogle Richard Wintle M.A., served as master 1864 to c.1869

Ogle Richard Wintle (1834-1875) was the son of Richard Thomas Wintle of Headinton Oxford shire, a doctor. Ogle Richard matriculated from Lincoln College on 2 June 1853 at the age of 19, served as a chorister of Christ Church College 1844-1849, achieved a BA and MA in 1862. He served as curate of Bridgwater 1864-1872 and was headmaster of King James’s Grammar School from 1864. On 2 May 1867 Hugo Edward the son of Ogle Richard and Virginia Wintle of Castle Street Bridgwater was baptised in St Mary’s Church Bridgwater. Richard was recorded as a clerk in Holy Orders. Richard conducted the baptism.

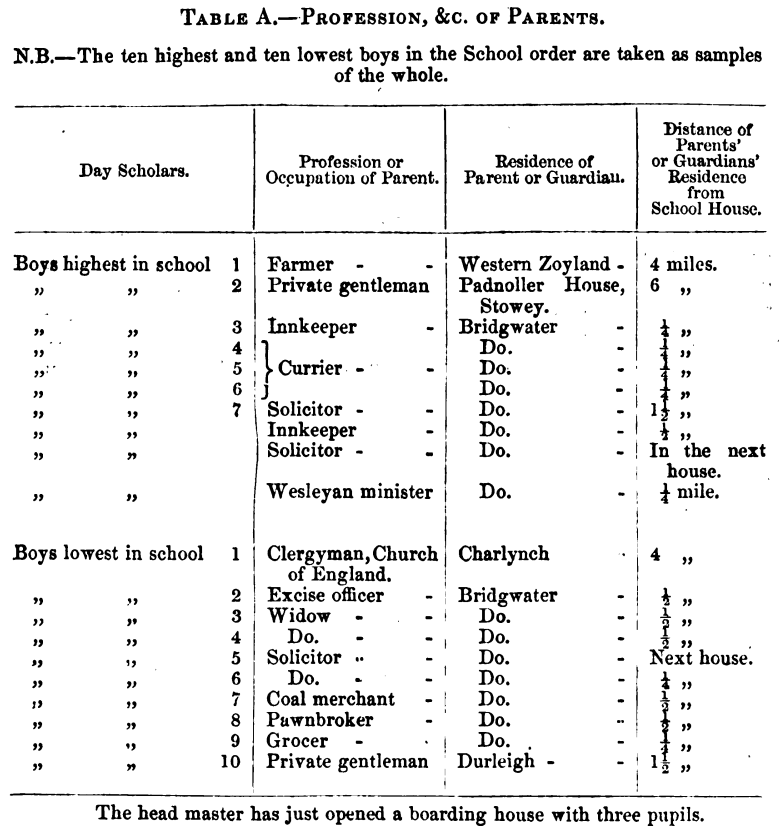

The school was described in the following way in the Schools Inquiry Commission, XIV, 1868:

BRIDGWATER. KING JAMES’ FREE SCHOOL. MR. STANTON’S REPORT.

With a population of 12,000, Bridgwater is but poorly provided with the means of education either for the upper or middle class. The grammar school endowment consists of nothing but £26 a year paid to a master, which is hardly earned by his being compelled in return to educate freely seven scholars, who are elected by competition at the half-yearly examinations out of the school. The original grant of King James of £6. 13s. 4d, representing a much larger sum now, was made to the master, “ad pueros biden et vicinis oppidis adjacentes bonis literis instruendum.”

The school was held in a private house rented by the master, in a street of the town, in a good situation, but necessarily circumscribed for space. There were no boarders at the school on my visit, but there were thirty day boys, sons of small clerks, and upper tradesmen. The master had only lately been appointed, and hoped, as a private enterprise, to raise a good day school, for which assuredly there is both room and material in the town. He intended as soon as he was more settled to take boarders. The £26 is partly derived from a charge on the tithes of the parish of Bridgwater, and partly from interest on some money in consols left by various individuals.

The boys were well taught, and their appearance and manner good. The course of instruction was chiefly classical, and considering that two-thirds of them had not passed more than six months their progress was satisfactory. There is a large and rich farming and mercantile population in this neighbourhood, and a good school for this class is much needed. Mr. Alfred Poole, an inhabitant of the town, who has interested himself in these matters, thinks that a school on the proprietary system, for the upper and supported class, or half events for the latter, would be supported well, both by farmers and tradesmen. With regard to Morgan’s school in this town, useful as that school is at present, I think it might be made yet more available for the growing wants of the neighbourhood.

DIGEST OF INFORMATION. (Ch. Com. Rep. xv. 424, A.D. 1826. )

Foundation and Endowment.By Queen Elizabeth, who, in 1561, granted a lease of the great and small tithes of the parish, subject to a charge of 61. 13s . 4d. per annum for the maintenance of a master. The charge was renewed in a grant by letters patent of James I. in 1613, and ultimately in a conveyance in fee of said tithes in 1706 to the corporation of Bridgwater. School Property. Besides the above-mentioned charge, there are two acres of land and 6281. 2s. 2d. consols, arising from sundry bequests and donations. Present annual income 291. 10s. gross, 28l. net. No school buildings or master’s house.

Objects of Trust.-“Uni pedagogo sive ludi magistro ad pueros et juvenes ibidem et oppidis vicinis adjacentes et ad illam confluentes erudiendum et bonis litteris instruendum.” ( Q. Elizabeth.) For six boys, to be elected from time to time by open competition, to receive gratuitously a good classical and general education. Other free scholars maybe nominated by donors of £100 and upwards (scheme).

Subjects of Instruction prescribed.-“Bonæ literæ.”

Government and Masters. New scheme approved by Master of the Rolls, 1 May 1857. Trustees, appointed by Court of Chancery, of the public charities of Bridgwater, consisting of the vicar and 14 other residents in the town, have the management of the property and power to prescribe general rules and regulations, subject to which the master controls the school, and can suspend, but not expel, a boy. Half-yearly examiners to be appointed, one by the trustees and one by the Bishop of Bath and Wells, who also appoints and may dismiss the head master. No qualification named for head master, and no restriction on other employment.

State of School in Second Half-year of 1867.

General Character. Classical. In age of scholars, first grade.

Masters Head master allowed to take boarders. Income, £28 from endowment, and fees from 28 boys not on the foundation. No house. Has Sunday clerical duty. A second master newly appointed, to be paid by head master. Drilling master to be paid by pupils’ fees.

Day Scholars. Twenty-eight, ages not stated, from distances up to six miles. Also seven free scholars. The rest pay £10 10s per annum, or £12 12s if over 12 years of age. Attend church on Sunday.

Boarders. Three. Four meals a day. Meat once, or twice if requisite. Terms 40 guineas. £2 extra if meat is given twice. Hours 7 a.m., 8½ to 10 p.m.

Instruction, Discipline, &c . Knowledge of simple rudiments necessary on admission.

School classified by one subject chiefly. School course slightly modified to suit boys. School open to all denominations . Prayers from liturgy morning and evening. Half an hour daily devoted to religious instruction.

Promotion by half year’s work and examination together.

Examination twice a year by two examiners, one appointed by bishop, and one by trustees. Book prizes given.

Punishments: impositions, detention, and caning; the last by head master only, and in school.

Playground of moderate size, close to school, open to all. No supervision out of school. No bounds prescribed.

[One boy at Oxford or Cambridge in May 1867]

School time 40 weeks per annum. Study 26 hours a week, besides about one hour a day for preparation. Play time 25 hours a week.

- LIST OF TRUSTEES, &c. ( 1867.)

- The Vicar of Bridgwater for the time being.

- John Browne, Bridgwater, Merchant.

- Robert Ford, Bridgwater, Retired Merchant.

- George Henning Pain, Bridgwater, Solicitor.

- Carey Bailey Mogg, Bridgwater, Merchant.

- James Haviland, Bridgwater, Surgeon.

- Gabriel Stone Poole Brent, Solicitor.

- John Trevor, Bridgwater, Solicitor.

- John Lovell Sealy, Bridgwater, Banker.

- Richard Smith, Bridgwater, Solicitor.

- George Parker, Bridgwater, Maltster.

- Richard Reynolds Woodland, Bridgwater, Banker.

- Joseph Richard Smith, Bridgwater, Pawnbroker.

- B. Lovibond, Bridgwater, Solicitor,

- Richard Axford, Bridgwater, Surgeon.

- William John Ford, Bridgwater, Bank Manager.

- Rev. John Collins, Incumbent of Saint John’s .

- Head Master : Rev. O. R. Wintle.

This is the last mention of Ogle as headmaster. Rev Ogle Richard Wintle ‘formerly Head of Bridgwater Grammar School’, died 12 November 1875 at Wing Rectory near Uppingham. He left effect under £2,000. He was recorded as late of Borthwick Boscombe near Bournemouth. [25] Virginia survived him and died in 1907.

Vaughan Benjamin Wintle B.A. served as master c.1871 to 1874

Vaughan B. Wintle (1837-1919) is mentioned as headmaster of the Bridgwater Grammar School in 1871, when he was gifted a silver cider flagon and a gold pencil case by the boys of his school as a birthday present. He was the younger brother of Ogle Wintle, and held a B.A. of Trinity College, Cambridge.[26]

Vaughan seems to have left Bridgwater 1874, as the house in Castle Street changed owner. He went onto to teach at Frome.

CASTLE-STREET, BRIDGWATER.

Sale of neat and substantial Household and School-room Furniture, &c.BABBAGE and BOYS will SELL by AUCTION,

on the premises, on TUESDAY, the 14th day of JULY, 1874, the undermentioned neat and substantial household and school-roomFURNITURE

And other effects of Mr. VAUGHAN WINTLE, of Castle-street aforesaid, schoolmaster, taken under an attornment of tenancy, viz.:—

In the Drawing, Dining, and Sitting-rooms.—Mahogany loo, telescope, dining, oak, Pembroke, deal, and other tables; walnut, mahogany, cane, Derby folding easy and other chairs; walnut couch, whatnot, pier glasses, bureau, crimson damask and muslin window curtains, with poles, rings, and fittings; wire and other blinds, carpets and rugs, fenders and fire sets, cocoa fibre matting, skin and fibre mats, chimney ornaments, spring dial, mantel clock, hand bell, stuffed birds, seven-octave cottage pianoforte, in handsome walnut case, nearly new harmonium, &c., &c.

The Bedrooms contain—Birch, half-tester, iron, and other bedsteads, with and without furniture; feather and flock beds, bolsters and pillows, wool, hair, and straw mattresses and palliasses; dressing tables, toilet glasses, washstands and ware, towel rails, chests of drawers, large linen wardrobe, cane and other chairs, hip and slipper baths, foot pan, water cans, carpets, druggets and rugs, stair carpeting, brass rods, floor and stair cloth, hand and other lamps, a quantity of bed and table linen, &c., &c.

Kitchens, Pantries, China Closets, &c.—Deal and other tables, chairs, stools and forms, steps, sets trays, plate rack, brushes, sundry plated articles, mats, knife basket, knives and forks, tea urn, saucepans, boilers, teakettles, fryingpans, breakfast, dinner, and tea services; cut decanters, wines and tumblers, hot-water, glass, and other jugs; glass dishes, metal and other teapots, handsome dessert service, salad bottle, mustards and salts, pickle bottles, jars and pots, glass and other sugar basons, 6 handsome cut-glass soda tumblers, lamps, oil cans, coffee mill, water cans, baking dishes, pudding moulds, bowls, sieves, coal boxes, beam and scales, coffee pot, sundry tin articles, galvanised buckets, and many other culinary requisites.

The School-room and Out-door Effects comprise—Several long and other school desks, forms, stools, chairs, easel, drawing and other boards, maps, pair of globes, long iron umbrella stand, fender and fire set, quantity of slates, stone roller, leaping bar and supports, blinds, sundry garden tools, scythe, flag poles, crosscut saw, &c.

Sale at Twelve o’clock at noon, to the minute.

NO RESERVE!

Dated Bridgwater, 8th July, 1874.[27]

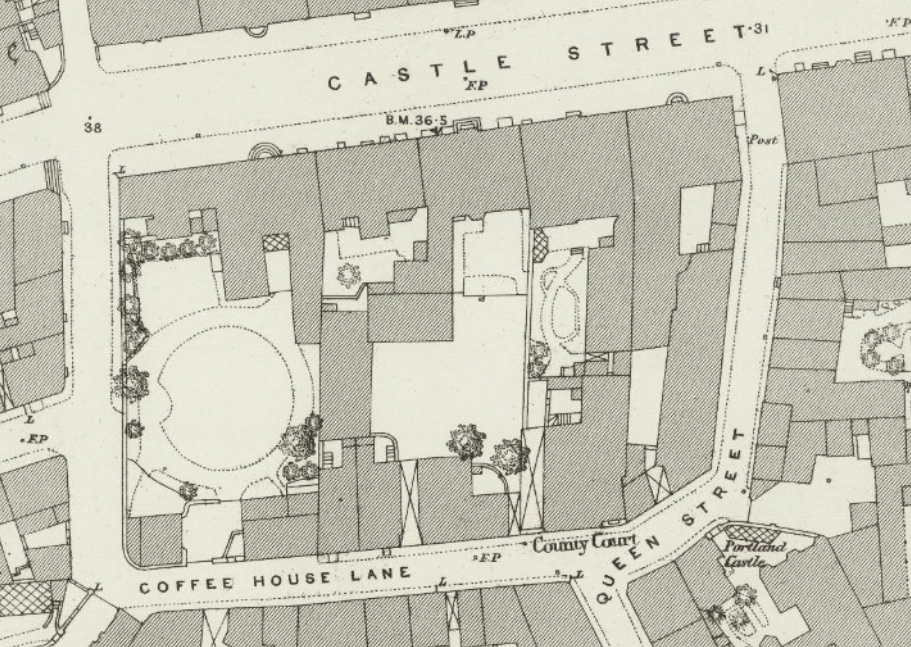

The property was then taken over by Boys Auctioneers, who describes it in Queen Street, rather than Castle Street. What seems likely is that the house in Castle Street backed onto Queen Street, with the building at the back being the schoolhouse, while the master lived in Castle Street. As such we can identify the property as 11 Castle Street (now the Arts Centre) and 10 Queen Street. By the 1887 OS Town Plan the Queen Street property had been hived off.

NOTICE. THOMAS HENRY BOYS, Auctioneer, Appraiser, House, Estate, Insurance, and General Agent, High-street, Bridgwater,

BEGS to inform the public that he has taken extensive premises in QUEEN-STREET (adjoining the County-court), BRIDGWATER, formerly occupied by Mr. Wintle, and known as “King James’s Grammar School,” which he intends forthwith opening as an AUCTION REPOSITORY, For the reception of all kinds of household furniture, implements, and other effects intended for sale, and holding therein periodical sales for disposal thereof by PUBLIC AUCTION.

Parties in town and county will find this an excellent medium for the disposal of property, and Mr. Boys will feel obliged with full particulars of entries intended for sale forthwith.

Mr. Boys tenders his most grateful acknowledgments for the kind patronage he has hitherto experienced, and hopes that by prompt attention to all matters entrusted to him to receive and merit a liberal and continued share of public support.

Offices, High-street, Bridgwater, October 30th, 1876.[28]

End of the Line?

With Vaughan Wintle leaving in 1874, the King James Grammar School de facto ceased to exist. However, de iure, it was still endowed, so there was a possibility that it might be revived.

There was a letter exchange in the Bridgwater Mercury through the later 1870s about the defunct school, which fills in details about some of the difficulties it had faced:

2 FEBRUARY 1876

KING JAMES’ SCHOOL. TO THE EDITOR. DEAR SIR, I was pleased to hear the remarks made at the Town Hall, by the Rev. W. Michell, Diocesan Inspector, and the Rev. J. W. Collins, respecting the necessity of having a high-class school in Bridgwater. Parents requiring a classical education for their children are obliged, at a great inconvenience, to send them from home or have recourse to private tuition. Are any of the trustees of King James’ School still living, or are they all defunct ? I can well remember when there were forty names on the register of the above endowed institution, fourteen of them boarders. Since then both the population and the wealth of the town have increased, and, therefore, a better chance of success. Many parents are very anxious that the Grammar School should be re-opened, and I hope the trustees will take the necessary steps to appoint a qualified master. Yours obediently, ARGUS.[29]

9 February 1876

KING JAMES’ SCHOOL. TO THE EDITOR

SIR, Your correspondent of last week, who seems to anxious to know why the trustees of King James’ School do not at once appoint a qualified master, may find the following facts useful as enabling him to answer his own question:

Some years ago vigorous efforts were made to place the said school upon such a footing as to give it every chance of success. Several people were induced to guarantee a certain salary for a fixed time, and the vicar was instructed to search for a fitting person to recommend to the bishop for appointment to the head mastership. A gentleman was found, duly qualified and possessing considerable experience, and an active canvass was instituted in order to obtain pupils for him. In spite of all this the school proved anything but a success, not from educational, but from social reasons.

In Bridgwater we have gentry and gentry, professional men and professional men, merchants and merchants, tradesmen and tradesmen, and, as is the case in all towns of similar size, everyone knows everything about his neighbour and his neighbour’s affairs, in fact, often more than his neighbour himself, and so there are multitudes of social lines which are impassable. If any man scoff at this, watch him and see if his actions do not belie his words.

It may not be generally known that for the sum of about £30 per annum the head master of King James’ School is bound to find accommodation for, and to educate, six boys in all respects as well as the rest of his pupils. These foundationers are elected by open competition, and may be the sons of anybody. Here, then, we have the secret of boys being sent to Taunton and elsewhere to school. True, they may meet with all sorts there, but they do not bring their associates home, and so no one is shocked. Unseen evils are rarely considered evils at all; if it were not so our pulpit orators would have much less to preach about than they have at present.

I believe it is the rule at Cheltenham that no tradesmen’s son living within thirty miles of the town can gain admission to the school. Something of this sort might be attempted at Bridgwater, but when the line was drawn between white and black sheep would there beenough of the former to supply the market, and, if not, with what chance of success would Bridgwater enter into competition with the more favourably-circumstanced schools of Taunton, Bath and Clifton to secure pupils from beyond the prescribed limits.

Lastly, is it not the rule of political economy that demand creates supply? Consequently, if there really is demand for a higher grade school in Bridgwater, how is it that we find laudable attempts which have from time to time been made by clergymen and others to lay the foundation of such a school, in the shape of classes for the sons of gentlemen and professional men, meet with so little success? That such attempts are constantly being made a recent advertisement in your columns abundantly proves, which stated that an M.A. of one of the universities (I forget which), living in the immediate neighbourhood of Bridgwater, was willing to prepare pupils for the public schools. Yours obediently, VERITAS.[30]

23 February 1876

KING JAMES’ SCHOOL. TO THIS EDITOR. Sir,—Will you permit me, through your columns, to ask “Veritas” if he will kindly state such particulars respecting the school in question as will enable myself and others interested in education to form a more correct opinion as to whether all possible has been done to resuscitate the school named or not?

I glean from the remarks of “Veritas” that there is a sum of about £30 per annum somewhere, realisable somehow, for the purpose of paying a master of the said school to educate six boys. Will ” Veritas” state the nature of the endowment, by whom and when founded, and from what source the sum of £30 is derivable? It is but a small amount- £5 each for six boys; but at the time of its foundation perhaps £30 per annum was a respectable sum, possibly equivalent to £150 or even £200 now, seeing how great a change has taken place in the increased value of property and the decreased value or purchasing power of money.

From “Veritas’s” allusion to the late master being recommended to the Bishop, it appears pretty clear the Church authorities have something to do with the appointment and Control of the funds. But the bishops and clergy of the Church are not always men of business habits; indeed, how can they be when, according to the nature of their studies, “their kingdom is not of this world,” they say. And, seeing how ardently “their affections are set on thine above,” it is no wonder they overlook many important changes taking place here below. It is only surprising that they have accepted so many duties of trust connected with mundane affairs, and managed them so well. It is very easy (for the least acquainted with business matters, on the great changes rapidly taking place in the value of all things) to be able to pay £30, simply because that sum is so named. According to the letter of the deed that may be quite right; but what I am anxious to show is, that in the altered condition of things £30 may not be in accordance with the spirit of the endowment, and does not represent the true value of the original sum, nor is it keeping pace with the times. How great “a change has come over the spirit of our dreams” even in our time! —and how much greater from the time of James to the present ! Hoping “Veritas” will supply the needful information, and, if possible, say what becomes of the funds while the school is closed, and, thanking you, Mr. Editor. for the necessary space to communicate with “Veritas,” I am, yours, &tc., Bridgwater, 14th Feb., 1876. OBSERVER.

1 March 1876

KING JAMES’ SCHOOL. TO THE EDITOR. SIR, “Observer” is welcome to all the information I can give him.

The original foundation of King James’ school is contained in a deed of February 15th, in the tenth year of King James I. (being a bargain and sale of the rectory and tithes of Bridgwater), from which the following is an extract :—” And shall also give and pay yearly to one pedagogue or schoolmaster, to teach and instruct in learning the boys and youths of the town of Bridgwater and resorting to the same, and in the adjoining neighbourhood, one yearly fee, stipend and salary of £6 13s. 4d., for the better in instructing, teaching and educating boys and youths there, and by the said rev. father (the Bishop of Bath and Wells) and his successors, and (the episcopal see being vacant) by the Dean and Chapter of the same see, for the time being, likewise from time to time to be named and appointed.”

In 1857 a scheme, “For the better regulation and administration of the said charities (of Bridgwater) for the application of the income thereof,” was prepared by Mr. Richard Smith, and received the approval of the Master of the Rolls in March, 1857.

In this it says: “The endowment will consist of an annual sum of £6 13s. 4d., charged upon the tithes of the parish of Bridgwater, now vested in the Mayor, aldermen and burgesses of the borough of Bridgwater; of the rent of Dorothy Holworth’s land at Blackland (two acres, now let on hire, and producing the annual rent of £4), and the dividends of the sum of £592 17s. Three per Cent. Consolidated Bank Annuities, on which Robert Balche’s charity of £180, Richard Castleman’s charity of £200, Richard Holworthy’s charity of £52, and another charity of t £100, heretofore given at a time unknown by Messrs. Crane and Parsons, in aid of the said school, are now invested, after payment of any costs which the Court I may direct to be paid thereout.”

The sum of £100, since presented by Mr. Richard Smith, for the purpose of founding an additional scholarship, has also been invested, and the dividend added to the annual income. It may be well to add that the Endowed Schools Commissioners sent one of their body to deal with the educational charities of Bridgwater, and King James’ Foundation was deemed too unimportant to be worth meddling with. I believe the commissioners reported that they had no evidence before them to show that a school of that grade would be generally acceptable to the town and neighbourhood. I am, Sir, yours faithfully, VERITAS.”

The End

In February 1884 the Charity Commission prompted the Town Council about money accumulating that was meant for the Grammar School, but was unspent. The Town Council resolved to dedicate it to a scholastic scheme of some sort.[31] In 1885 Sydney Gardnor Jarman’s Handbook of St Mary’s Church mentions the school’s endowment, but that the school was in abeyance ‘pending instructions from the Charity Commissioners’ (page 39). However, the Charity Commission replied that the money should be used for the intended purpose of supporting the Grammar School, and could not be redirected to another school.[32] It would not be until 1888 that the money for the defunct Grammar School was finally allocated to support Dr Morgan’s.[33]

MKP 8 November 2025

with materials gathered by Peter Randle, Jill Trethewey and Clare Spicer

[1] Dunning, Victoria County History.

[2] Lawrence, History of Bridgwater; Somerset Heritage Centre D/B/bw/CL/30.

[3] SHC D/B/bw/1825.

[4] See https://bridgwaterheritage.com/wp/historical-sources/descriptions-of-the-town/stephen-whatley/

[5] Sherbourne Mercury 30 November 1801.

[6] The Bullers were a well established family in Stowey at this time. There were three main lines:

1. On 28 February 1742 Richard the son of Richard and Betty Buller was christened at Nether Stowey. On 30 June 1742 John the son of Richard and Betty Buller was christened at Nether Stowey. On 4 January 1744 Betty the daughter of Richard and Betty Buller was christened at Nether Stowey

2. On 12 May 1743 Elizabeth daughter of William and Jane Buller was christened at Nether Stowey. On 27 June 1745 William the son of William and Jane Buller was christened at Nether Stowey. On 27 February 1746 Sarah the daughter of William and Jane Buller was christened at Nether Stowey. On 12 January 1750 Christian the daughter of William and Jane Buller was christened at Nether Stowey. On 9 October 1753 Mary the daughter of William and Jane Buller was christened at Nether Stowey.

3. On 22 March 1755 Mary the daughter of Richard and Sarah Buller was baptised at Nether Stowey. On 2 March 1757 Sarah the daughter of Richard and Sarah Buller was christened at Nether Stowey. On 9 January 1759 Robert the son of Richard and Sarah Buller was christened at Nether Stowey. On 30 June 1764 Robert Beadon Buller the son of Richard and Sarah Buller was christened at Nether Stowey.

[7] Exeter Flying Post, 12 January 1826

[8] Sherborne Mercury, 30 April 1838

[9] Sun (London), 9 February 1835

[10] Bristol Times and Mirror, 01 November 1845

[11] Dorset County Chronicle, 05 March 1840

[12] Dorset County Chronicle, 02 July 1840

[13] Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser, 03 March 1841

[14] Bristol Mirror, 21 January 1843

[15][15] Bristol Times and Mirror 01 November 1845

[16] Bristol Mirror, 21 March 1846

[17] Royal Cornwall Gazette, 06 July 1849

[18] Wells Journal, 24 July 1852

[19] Western Courier, West of England Conservative, Plymouth and Devonport Advertiser, 11 August 1852

[20] Wells Journal, 24 July 1852

[21] https://archive.org/details/atestbookforstu00stangoog

[22] Bristol Times and Mirror, 20 September 1862

[23] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 26 February 1863

[24] Belfast News Letter 14 Apr 1906

[25] Leicester Journal, 19 Nov 1875

[26] Oxford Journal, 19 February 1919

[27] West Somerset Free Press, 11 July 1874

[28] West Somerset Free Press, 24 March 1877

[29] Bridgwater Mercury, 2 February 1876

[30] Bridgwater Mercury, 9 February 1876

[31] Western Gazette, 22 February 1884

[32] Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser, 4 February 1885

[33] Dunning, Victoria County History