This is the story of three Bridgwater women, Mary Ann, Emma and Selina, who put aside their own difficulties to help other women in their time of need. The little extra income they earned may have been useful, but helping young mothers who are frightened and in pain isn’t easy, and midwives often have to go out at night and in all weathers, as babies don’t always arrive at convenient times.

Women were not the traditional breadwinners in the 19th century so their work was often overlooked in official records. Recently the Wembdon Road Cemetery Stillbirth Register has been digitised and is now online. The Bridgwater midwives are named, no longer invisible. Of course midwives are best remembered for the many mothers and babies they delivered safely in the days when many women could not afford a doctor.

Most 19th century midwives began as experienced mothers themselves, and started by helping neighbours and relations during pregnancy and giving birth. On occasion when a doctor had to be called, the midwife could observe and assist, and so learn how to help in more unusual cases.

Throughout the 19th century, there was no regulation for midwives in the UK, and this contributed to midwives having a poor reputation in some quarters. However, in a town like Bridgwater, there would have been a local ‘court of public opinion’, whereby a midwife’s reputation for honest hard work, sobriety and success, was well known locally. A midwife’s good reputation was vital in getting work, and in getting paid for that work.

Giving birth was considered a normal function and poor women did not usually get qualified medical assistance. There would have been little or no pain relief for mothers in labour. Childbirth may have been considered a normal function, but it was a highly risky one during the 19th century. At this time there was still little understanding of the causes of infection, and doctors, nurses and midwives could unknowingly carry germs from patient to patient. Maternal deaths were often due to puerperal fever, which was caused by infection.

Wembdon Road Cemetery Register of Stillbirths 1871 – 1922

At the end of a challenging night that had resulted in a stillbirth, the weary midwife had to put aside her own feelings a little longer and help the family attend to the administrative requirements of registering a stillbirth with the registrar, to allow burial. A stillbirth was the term for a baby who was born dead. Births and deaths had to be registered in England and Wales from 1837, but there was no requirement to register stillbirths in England until 1926. However, the Births and Deaths Registration Act of 1874 tightened up on regulations, and the Wembdon Road Cemetery officials began keeping their Stillbirth register ahead of this act coming in to force.

There are many stories around the burial of unbaptised people, and the official position of the Anglican Church at that time was that unbaptised individuals could not be buried in consecrated ground. However, there is considerable anecdotal evidence that various ways around this were found, especially with a sympathetic priest and cemetery staff. The opening of a large cemetery such as Wembdon Road, with unconsecrated land available for use by non-conformist churches, probably also eased the situation.

One of the first midwives recorded in the Wembdon Road Register was Nurse Pole, who practised as a midwife from the 1860s to the 1870s, and so represents the time when there was no formal training, no antiseptics used and little medical intervention.

Mary Ann Pole nee Turner 1793 – 1878

Mary Ann Pole, nee Turner, was one of the first midwives identified as such on the Wembdon Road Cemetery Stillbirth Register. Mary Ann was born and bred in Bridgwater, the daughter of shopkeeper William Turner and his wife Sarah.

Mary Ann married brickyard labourer George Pole on the 9th of October 1814 at St Mary’s Church Bridgwater. George could sign his name, but Mary Ann couldn’t write and just made her mark. They lived in Halswell House Lane for most of their married life, and had at least eight children, so Mary soon became experienced in childbirth. The 1841 census shows George and Mary living together with seven of their children all squeezed together into a small house. Mary’s widowed father William was living nearby in West Street.

Ten years later, the 1851 census showed an even more cramped household. George and Mary were still living in Halswell House Lane, George was 64 and still working as a labourer in a brickyard, which would have been very heavy work for a man of his age. Only two of their younger sons were living with them, but also there was their daughter in law Eliza Pole and eight grandchildren, ranging in age from ten years to three months. Five of these grandchildren were born in Bridgwater, and Mary must have helped at their births, adding considerably to her experience. With eight small children in the house, Mary would have spent her days washing and cooking.

Less than a year later, George Pole died at the age of 65, from asthma. As someone who had worked in a brickyard for much of his life, George would have inhaled a lot of brick dust, and this was probably the cause of his illness. With her children now mostly grown up, Mary Ann was left without a source of income, and she left her home in Halswell House Lane and moved into accommodation in West Street. Her married son Francis, his wife Mary, and three small grandchildren were also living with her. Mary Ann probably began working as a midwife soon after her husband’s death.

In 1861 Mary Ann described her occupation as a nurse, and she is referred to as Nurse Pole in the Wembdon Road register. Mary Ann Pole was illiterate, so she would have had no formal training as a nurse. In the Nineteenth century, new mothers often employed someone as a ‘monthly nurse’. This was someone who was a ‘mother’s help’, who would live in for a few days and help to care for both the new mother and baby. This person might also be a midwife who helped with the birth, although some women only worked as monthly nurses. Mary Ann Pole must also have worked as a midwife, because she was recorded on the Stillbirth register, so must have been present at the birth and reported the death to the registrar in order to get the necessary certification for burial.

By the 1871 census, Mary Ann Pole was, rather alarmingly, still working as a midwife at the age of 78. She was lodging in West Street with James Turner, possibly a relation. Also with Mary Ann were two of her Pole grandchildren.

Mary Ann continued to work for another three years. The Wembdon Road Stillbirth Register shows nine records for her, all between March 1871 and March 1874, although of course, she would have attended many more successful births. Four of these stillbirth records were in 1873, and the total stillbirth burials recorded in the Wembdon Road register for 1873 was 20. St Mary’s church baptism register recorded 90 baptisms in this year.

Mary Ann continued to work for another three years. The Wembdon Road Stillbirth Register shows nine records for her, all between March 1871 and March 1874, although of course, she would have attended many more successful births. Four of these stillbirth records were in 1873, and the total stillbirth burials recorded in the Wembdon Road register for 1873 was 20. St Mary’s church baptism register recorded 90 baptisms in this year.

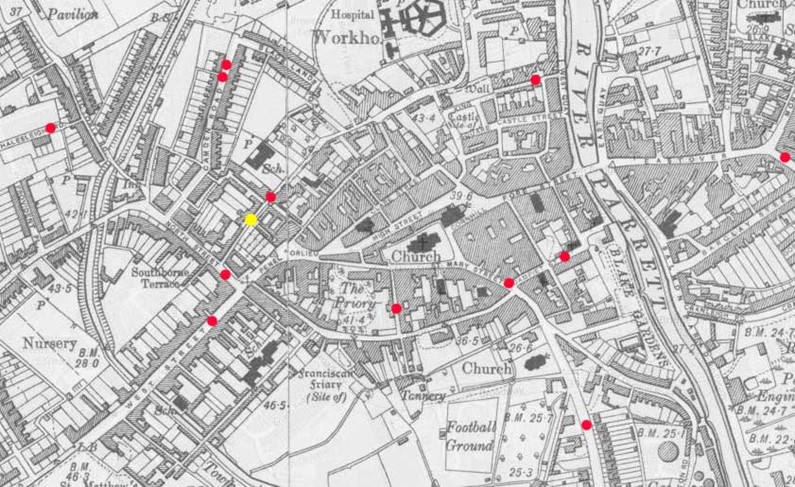

The records show Mary Ann Pole working in North Street, Pricketts Lane, West Street, Pig Market, Mount, Horse Pond Lane and Somerset Place. The red dots on the map below show the streets she visited, the house numbers are not known. The yellow dot marks her home in West Street, although again, her house number is not known. This map shows that Nurse Pole mainly worked within a short walking distance of her home in West Street. The streets she visited were generally associated with poor, cramped housing

Mary Ann Pole enjoyed about three years of retirement after a long life of hard work. She died at the end of May 1878, and was buried on the 3rd of June in Wembdon Road Cemetery, Section 1.

Causes and control of infection

When Nurse Pole was working as a midwife in the 1860s and 1870s, the medical establishment as a whole had little understanding of the causes of infection. In the late 18th century and early 19th century, Scottish physician Alexander Gordon and Hungarian physician Ignaz Semelweis realised that medical staff were inadvertently transmitting infection on their hands and clothes. Semelweis demonstrated that the simple process of washing hands with carbolic soap greatly reduced the transmission of infection, but both Semelweis and Gordon were disbelieved and treated with ridicule by the medical establishment. Instead there was a widespread belief that infection was carried by ‘bad air’, or odours.

Joseph Lister (1827 – 1912) was important in introducing the use of antiseptics such as carbolic acid, but it was not until the 1920s that face masks and rubber gloves began to be used during obstetric procedures in hospitals and home births.

In September and October 1881, there were articles in the West Somerset Free Press describing a sad case in Bristol. Four women in a row had died of puerperal fever caused by infection, all attended by the same midwife, who was then ordered to stop work for a month. This showed that there was then some understanding that infection caused the fever, and there was a clear link to the midwife. The coroner told the distressed midwife that she was not to blame, so there may not have been an understanding of the means to prevent the spread of infection, other than isolation.

There is a gap in the records for the Wembdon Road Stillbirth Register from February 1881 to October 1889. The first record in 1889 is for Emma Pitman, midwife. During Emma’s career as a midwife, she would have become increasingly aware of the risk of infection in her work.

Emma Pitman nee Duddridge 1849 – 1915

Emma was born and brought up in Bridgwater. She lived with her parents William and Sarah Duddridge in Barclay Street, and William was a brick maker.

By 1861, the family had moved to Old Basin, Huntworth, in the parish of North Petherton, where William Duddridge was a foreman in the brickyard. Close neighbours were the family of John Pitman, which is probably how Emma met her future husband. On the 23rd of November 1866, Emma married Frederick Pitman at the parish church in North Petherton. Frederick was a labourer and could sign his name, Emma could not write and made her mark.

Within a year Frederick and Emma had their first child, a daughter Sarah. Another daughter Elizabeth was born in early 1871. The census in 1871 shows Frederick and Emma living in North Petherton, close to Crossway House which was occupied by John Symons, manager of the tile works. This was probably where Frederick Pitman was working.

Frederick and Emma had another four daughters between 1873 and 1888, although sadly two of them died very young. Rather unusually for the time, Emma seems to have started work as a midwife soon after the birth of her last daughter Emma Etheline. By 1888, the family had moved back into Bridgwater town and were living in Mount Street. Emma’s eldest daughter Sarah was old enough to help take care of the baby when she wasn’t working as a dressmaker. This was a time of unrest and strikes in the brickyards, which would have been difficult for Frederick, as a foreman, and his wages may have been affected. The move into Bridgwater also provided Emma with a larger scope for her midwifery work.

On the 1891 census, Emma gave her occupation as ‘monthly nurse’. Emma was clearly a very busy midwife, and sadly her name appears quite frequently on the Stillbirth Register, although there is no record for the large number of successful births she must have attended.

In September 1897, Emma was called as a witness to give evidence at an inquest, in her professional capacity as a midwife. The fact that she was called as a witness indicates that Emma was respected for her work and her reliability. Emma explained that she had attended the mother during the birth of her baby, and for about a week afterwards. She gave her opinion that the baby had been born slightly undernourished and was not healthy. Emma went on to describe how she had seen the mother with the baby on subsequent occasions around the town, and noted that the baby had not grown much and still seemed very under nourished. This shows that although midwives had no official continuing responsibility after the birth, Emma was alert to the developing health of babies that she had delivered. The mother was then charged with manslaughter by neglect, and Emma Pitman had to give her evidence again at the magistrate’s court. This time, Emma added to her evidence that there was no food at all in the mother’s house, when she had been there attending the birth. Evidence given by other witnesses showed that excessive drinking by both parents was a major factor. The case was committed for trial at the next assizes.

Emma was probably well aware that plans were underway for regulation and training of midwives. The Midwives Act of 1901 provided a framework for the formal training and certification of midwives. District Councils were responsible for collecting records locally. Midwives who were currently in practice in 1901 had to register and were subsequently allowed to become certified midwives if local authorities were satisfied that their work was of a good enough standard. This was in lieu of formal training or exams.

The 1901 census shows Frederick and Emma still living in Mount Street, at a house called Mulgrave Villa. Frederick was still working as a brick maker, and Emma’s occupation was ‘midwife’. In 1904, Emma appeared for the first time on the Midwives Roll, her registration number was 5717, so she was now a certified midwife, her qualification being that she was ‘in practice in 1901’. Emma must have been proud of this formal recognition.

1904 was also a busy year, Emma has nine records on the Wembdon Road Stillbirth Register, out of a total of 24 records for that year. There were 100 baptisms in St Mary’s Church for the same year, but the total birth rate for Bridgwater town would have been higher. (See notes at end).

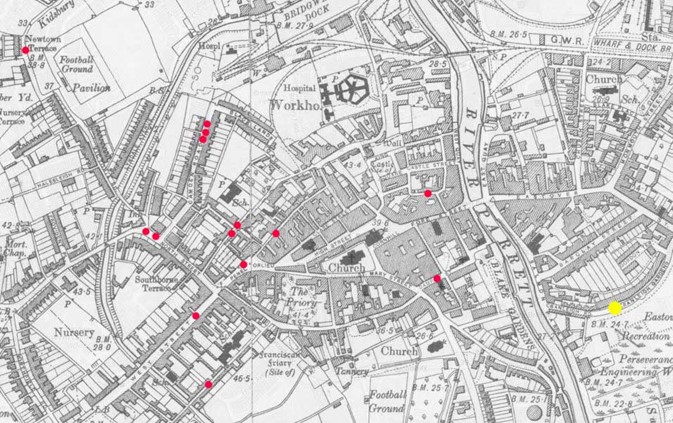

In 1904, the Stillbirth Register shows that Emma Pitman worked in Camden Road, Dampiet Street, Taunton Road, Halesleigh Road, Silver Street, St Mary Street, Chandos Street, St John Street, West Street and Mount Street. Another midwife, Mary Ann Owen was also working at this time, and they seem to have occasionally worked in the same streets, so there doesn’t seem to be a particular area that each midwife kept to. The yellow dot on the map below marks Mount Street, where Emma was living. Her house number is not known.

Emma seems to have worked over a wider area than Nurse Pole, although she was still visiting some of the poorer areas. Bicycles were available during the 1890s, but were an expensive item to buy, and it is more likely that Emma did a lot of walking to visit her patients. Although both Emma Pitman and the next midwife Selina Bater visited some of the poorer streets, there are not as many records as might have been expected in the densely populated roads and courts around West Street and Albert Road. This could be because midwives had to be paid for, so some women might try to manage with only the help of friends and relatives.

In 1911, Frederick and Emma were still living in Mount Street, together with their married daughter Ellen, son in law Joseph Paull and young granddaughter. Frederick was still working as a brickyard labourer aged 67, Emma, 63, described herself as a ‘monthly nurse’, although she was entitled to call herself a certified midwife. The last record for Emma on the Stillbirth Register is in February 1912.

Emma Pitman died aged 66 in early December 1915, and she was buried on the 15th of December in Wembdon Road Cemetery, left margin Plot 2, Section 4. Her husband Frederick died in September 1921, and was buried with her.

Emma Pitman’s midwifery career began in the 1880s, a time when many midwives were still illiterate, and there was little knowledge of the causes of stillbirth, maternal and neonatal death. However, by the end of her career in 1912 there was an understanding of the use of carbolic soap and sprays to reduce infection. After much campaigning, the Midwives Act of 1901 introduced a proper system of training, formal examination and certification for midwives, and Emma was able to be included on the Midwives Roll, because of her long experience and successful work.

One of the last midwives recorded on the Wembdon Road Stillbirth Register was Selina Bater, and her career reflects the development of midwifery into modern, twentieth century medicine.

Selina Bater Lane nee Kitch 1874 – 1945

Although some training and a midwifery qualification had been available from the London Obstetrical Society during the 19th century, the cost of the training and certificate was beyond poorer women. This meant that most midwives in the 19th century still relied on practical experience for their education. However, the 1902 Midwives Act provided a formal framework for the training, examination and certification of all midwives. Selina Bater nee Kitch was a Bridgwater midwife who passed a formal exam to become qualified.

Selina Kitch was born in North Petherton in 1874. Her parents were Thomas and Ann, and her father Thomas was a labourer. By the time Selina was 16 she had moved into Bridgwater and was working as a domestic servant. A couple of years later in 1893 she met and married her first husband, Charles John Bater, a self-employed boot and shoe maker.

Selina and Charles had their first child Annie about a year later. A son Harold followed and by 1901, the Bater family were living in Barclay Street, Bridgwater. A second son, Stanley, arrived in 1902. Selina’s younger sister Julia was working as a certified nurse in Bromley, Kent, by 1907, and this may have encouraged Selina to begin a new career. Selina and her children were still living in Barclay Street in 1911 and Selina was working as a self-employed monthly nurse. Her husband Charles has not yet been found on this census, and he may have either moved away, or died.

Selina qualified under the new regulations set out under the Midwives Act of 1902. She passed the written examination for the Central Midwives Board (CMB), and she must have had a period of at least three months training at an approved centre before this, as well as keeping a register of the required 20 midwifery cases. At this time there were no CMB approved teaching institutions for midwives in Bridgwater. Bristol had the nearest teaching hospitals, but Selina also had her sister Julia and a brother living in Greater London. It is possible she trained at a London hospital, as her second husband was a Londoner.

Selina would have left her children in Bridgwater in the care of relatives while she was away training. Her father was living with her by 1912, so it is likely that her retired parents moved in from North Petherton to live in Selina’s house in Barclay Street, and help her with the children.

The examination Selina had to pass included anatomy, the mechanisms of normal pregnancy and complications, the course and management of normal labour, signs of abnormal labour, treatment of haemorrhage, care of puerperal women, care of infants and signs of early disease, use of antiseptics and principles of hygiene. Selina had to learn how to use equipment such as thermometers, catheters and a pinard horn for listening to a baby’s heartbeat. She also had to learn about commonly used drugs and how to administer them.

Selina passed her CMB exam and was admitted to the Midwives Roll on the 19th of February 1912. Her roll number was 35155 and she was still living at 78 Barclay Street. Selina’s pleasure in this success would have been tempered by the sadness of losing her father less than a year later. He died at Selina’s home in Barclay Street on the 31st of December 1912. Her widowed mother may have continued to live with Selina while Selina went out to work.

By 1913 Selina and her children moved to a nearby road called Cranleigh Gardens. Selina would have been working independently like Mary Ann Pole and Emma Pitman, employed directly by the mothers to be.

Selina Bater appeared as a midwife on the Wembdon Road Stillbirth Register between 1913 and 1916, and after this time she was probably living and working in Westonzoyland. When she was working in Bridgwater, Selina visited Camden Road, Mount Street, West Street, Northgate, Cattle Market, Albert Street, Queen Street, Market Street, Newtown and Dampier Street. Some of the roads were visited more than once. The red dots on the map below mark the roads she visited, although not the actual properties. The yellow dot indicates Cranleigh Gardens where Selina lived while working as a midwife in Bridgwater.

Charles Bater must have died by early 1916, as Selina married again on the 3rd of May 1916, in the Register Office in Bridgwater. She married Londoner Denis Lane, who was a corporal in the 5th Battalion, King’s Own Shropshire Light Infantry, on active service during WWI. 1916 was a time of great change for Selina, she remarried in May, her mother died at the beginning of June, and at the end of June her elder son Harold left home and joined the Royal Navy, aged 16.

Denis was discharged from the army in 1919, with a disability, and the couple lived on a small holding in Westonzoyland. Selina continued working as a midwife, working independently as before. The 1921 census showed Denis and Selina living on their small holding, called Suffolk House. Selina was a self-employed midwife, and her daughter Annie Bater was living with them and assisting her mother as a nurse. By the end of 1922, Selina was joined in Westonzoyland by her daughter in law Elsie Alexandra Bater, the wife of Selina’s son Harold. Harold would have been away at sea a good deal, and his wife Elsie also trained and worked as a midwife. She was entered to the Midwives Roll on the 13th of December 1922, and was living at Laurel Dairy in Westonzoyland.

The Mary Stanley Training Home opened in Castle Street, Bridgwater In 1921. This provided training for District Nurses and Midwives, and also became a maternity home. Future midwives would be able to get their formal training in Bridgwater.

The work of midwives also changed during the 1920s when for the first time they began to be involved not only in birth but also in pregnancy care, as part of a drive to reduce the incidence of pre-eclampsia. This is a relatively rare, but potentially fatal complication of pregnancy, and midwives took on the important role of monitoring pregnant women by routinely testing urine and measuring blood pressure.

The Second World War started in 1939 and Selina’s son Harold was still on active service with the Royal Navy. He was now a supply chief petty officer based on HMS Tamar, which was a hulk moored in the Royal Naval dockyard in Hong Kong. HMS Tamar was used as an executive shore base for the Royal Navy. Harold was captured by the Japanese Imperial Army, probably during the battle for Hong Kong in December 1941. This battle began only hours after the attack on Pearl Harbour, and lasted for 18 days. He was held in a Japanese prisoner of war camp at Osaka, where he died of dysentery on the 25th of October 1942. He was buried in the Yokohama British Commonwealth War Cemetery. Selina would not have been able to travel to visit Harold’s grave, and his wife Elsie was left a war widow with three sons, the youngest only four years old.

When the 1939 census was taken, Selina was still working as a midwife, and living in Suffolk House with her husband Denis Lane. If she continued to work as a midwife, or at least follow medical news, she would have just seen the early introduction of antibiotics into general medical use in the mid 1940s. Antibiotic medicines finally produced a dramatic decline in maternal deaths, which had been at a fairly stable rate during the second half of the 19th century, and only gently declining during the first part of the 20th century.

Selina lived at Suffolk House in Westonzoyland for most of the rest of her life, but she died in Bridgwater on the 17th of June 1945. Her husband Denis lived another two years and died in 1947.

Selina and Denis died shortly before the introduction of the National Health Service in 1948, but Selina saw many important improvements in maternity care during her career.

Postscript: Family memories of Selina Bater Lane and Elsie Bater, told by Steve Bater

When Selina (my great grandmother) and her second husband Bill Lane had the small holding at Suffolk House they had some cows and Bill Lane used to deliver milk on a motorbike and side car. My father (Alexander Bater) remembered helping to deliver milk from churns on the flat side car in the St John Street area, ladling milk from the churns into jugs etc that were brought out by the housewives.

Selina’s daughter-in-law Elsie Bater (my grandmother) also worked as a district nurse at Rode, which is north of Frome, but I remember her mostly from the 1950s onwards. In the fifties she was joint owner and Matron of the Drummuir Nursing Home in Northfields, Bridgwater.

Notes

Wembdon Road Cemetery Still Birth Register

This register recorded the names and addresses of parents, then the name of the midwife, doctor or other person bringing the body for burial, the gender of the baby and the date of interment. The location of the burial is not recorded. The register has records from 04/02/1871 to 22/04/1922.

There is a gap in the record between February 1881 and October 1889. Also some other years have no records, and some years seem to have gaps of several months. It is hard to account for this. Still births can be caused by maternal infection, so an increase in infection in the town might account for sudden increases in numbers. But perhaps some burials were simply not recorded on this register for some reason, or some were taken to another burial place.

Births in Bridgwater

The statistics for births in Bridgwater show that there was a sharp decline in the birth rate between 1891 and 1911. Bridgwater was following the national trend for a rapidly declining birth rate at this time, the causes of which are still a subject of debate.

The table below shows statistics for births and still births, for Bridgwater in 1877, 1891 and 1911, the times when the three midwives were working.

| Description | 1877 | 1891 | 1911 |

| Estimated annual live births in Borough of Bridgwater (approximately half of those in the Bridgwater registration district.) * | 531 | 526 | 396 |

| Estimated annual births notified quarterly to the Borough of Bridgwater.** | 532 | 388 | n/a |

| Annual stillbirths in the Borough of B/W from WRC stillbirth register – selected examples. | 20 in 1873; 8 in 1877 | 1 in 1890; 0 in 1891; 2 in 1892; 13 in 1893 | 24 in 1904; 6 in 1910; 5 in 1911; 2 in 1912; 15 in 1913 |

*Birth certificates issued in the Bridgwater registration district include those in surrounding farms and villages. Birth certificates were only issued for live births.

** The number of live births in the Borough of Bridgwater notified to the Bridgwater Rural Sanitary Authority as part of the quarterly Health report, is reported sporadically in the Bridgwater Mercury prior to 1900. The births notified were approximately half the total for the Bridgwater registration district in 1877.

Friends of Wembdon Road Cemetery biography of Mrs Mary Ann Pole’s grand-daughter Caroline, with more about the Pole family: Caroline Pole 1848-1856 – Friends of the Wembdon Road Cemetery

References

Ancestry.co.uk – Wembdon Road Cemetery Stillbirth Register, Census records, the Midwives Roll and Royal Navy Registers of Seamen’s Services.

British maternal mortality in the Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries – Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

Mary Stanley Nursing Home, Bridgwater – SW Heritage Catalogue

The British Newspaper Archive:-

- The Bridgwater Mercury 09/02/1878 and 15/09/1897

- Wells Journal 22/10/1891

- West Somerset Free Press 21st September and 1st October 1881

British History Online – Victoria County History for Somerset – History of Bridgwater

https://www.somersetheritage.org.uk/

Free index of registered births, marriages and deaths in the UK.

Royal Navy Research Archive – HMS Tamar

Clare Spicer, Hilary Southall and Jill Trethewey, 22/01/2022.