Chapter three of Rev. Arthur Powell’s Ancient Borough of Bridgwater (1907) is dedicated to the supposed lost church of St Bridgit.

The chapter starts by translating one of the hundreds of medieval documents in the Borough Archives, and details how a William of Wembdon donates a meadow in Crowpill to ‘Peter of Bruges, rector of the church of St Bridget’. The rest of the chapter goes on to talk about Crowpill and the saint, then speculates where the church might have been. The whole chapter can be read here. More on St Bridgit of Kildare can be read here. Here is Powell’s translation of the document:

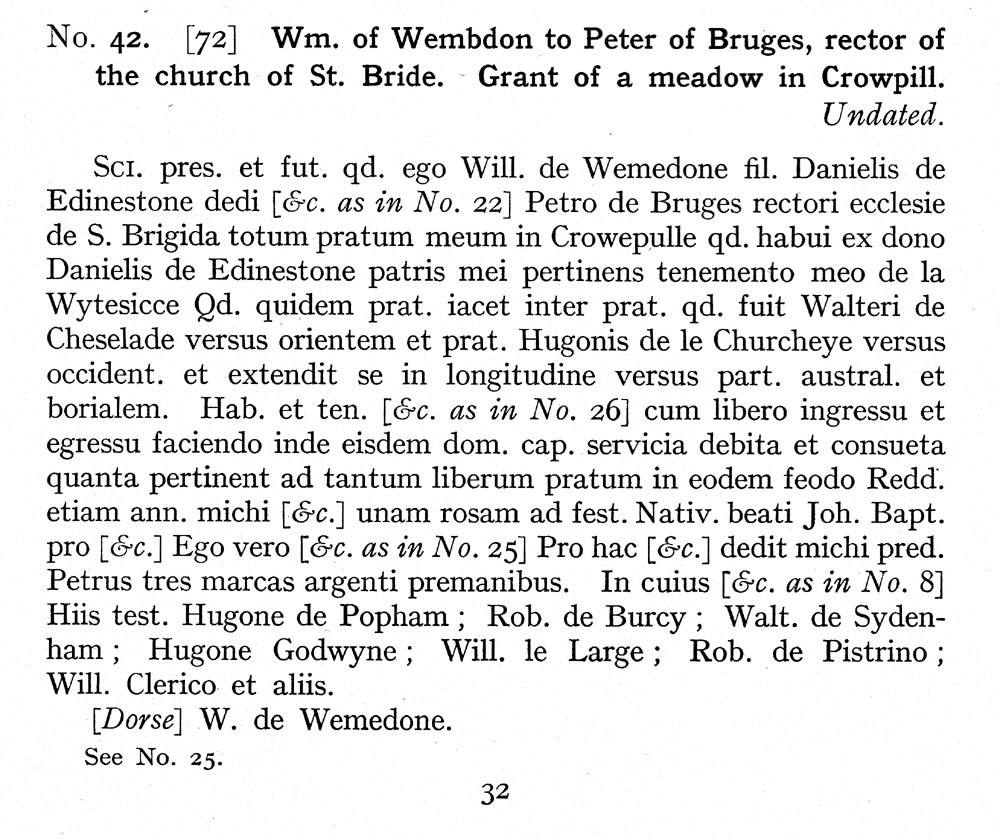

A transcription of the original Latin document was published by Thomas Bruce Dilks in the first volume of his (as yet unfinished) Bridgwater Borough Archives, volume 1, 1933, document number 42, which is dated to an unknown time in the 1290s. Dilks does not discuss this document in his introduction.

There are a few interesting yet infuriating features of this document.

By far the most important thing is this charter gives no indication at all as to where this ecclesie de S. Brigida is. It could be in Wembdon, it could be in Bridgwater, it could be on the moon: the text does not clarify. In favour of it being local is that no further clarification is apparently needed, otherwise we might expect something like ‘in the county of Xshire’, but even then a diligent clerk might be expected to say ‘in this parish’. It is important to note the emphasis here though: the church of St Bridgit is incidental, Peter of Bruges is the important subject , as recipient of the transaction in exchange for the three pieces of silver.

A key word in the text is ecclesie of Saint Bridgit, the church. The word used is not capella, meaning chapel. Through the middle ages, the parish of Bridgwater had many chapels. There were some inside the Church of St Mary’s, in the next century we learn of a chapels of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Saint Katherine and All Saints, with more to follow thereafter. Others were freestanding elsewhere, such as a chapel at Horsey (a ‘chapel of ease’, dependent on St Mary’s), a chapel of St Mark in Bridgwater Castle, or, in later centuries, St Saviour’s outside the South Gate.

Wherever this church of St Bridgit was, we can infer it was of some standing, being far more than a mere chapel, and possessing its own rector, someone with the important office of managing it. Yet Bridgwater already had a ‘church’, St Mary’s. The Hospital of St John and the Franciscan Friary had ‘churches’, but they were for the use of their holy communities and not the wider parish. It is difficult to see how an additional church could fit into the parish of Bridgwater. Chapels yes, churches no.

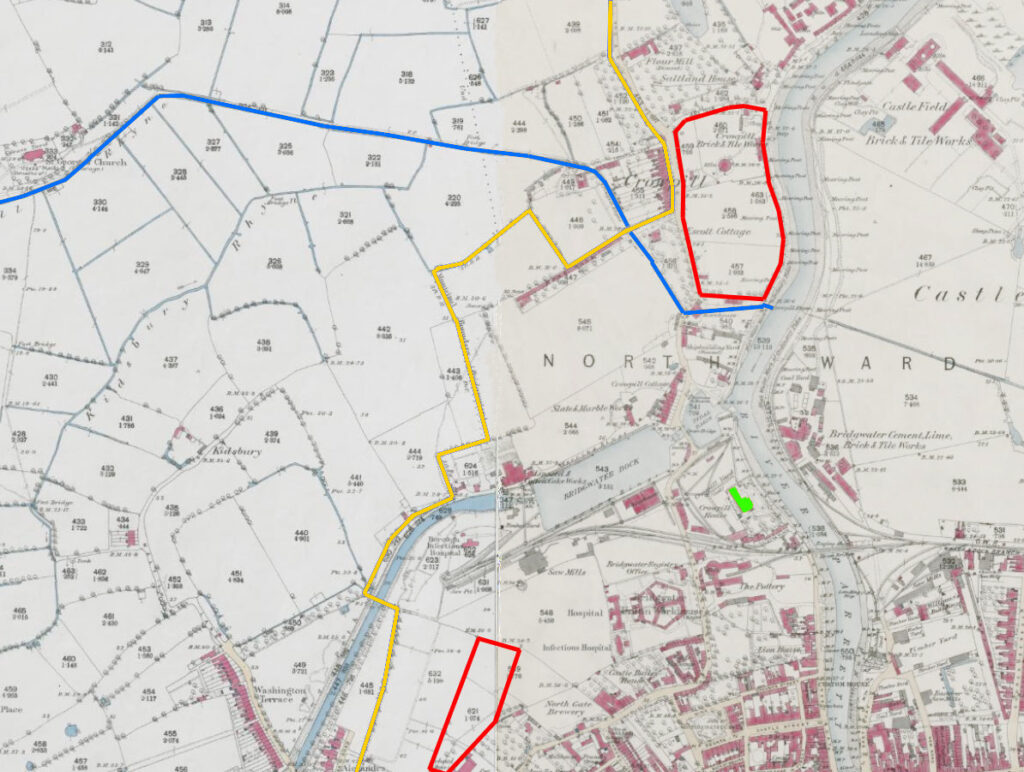

Could this church be a neighbouring parish church perhaps? Wembdon was dedicated to Saint George by 1284, so it is not there. The medieval dedication of Durleigh’s Parish church is unknown (which is very weird), although it is now dedicated to Saint Hugh. Could this be the church of St Bridgit? This is not impossible: tantalisingly, there are some fields in the vicinity of the Crowpill area, one called Little Blacklands, and another adjoining the river, which were part of Durleigh Parish, little detached islands in what is otherwise Bridgwater Parish, near the boundary to Wembdon. Might one of these oddities be explained by this charter of William of Wembdon? The field next to the river might be discounted. The charter mentions fields on the east and west sides: to the east of this one is the river. The Blacklands field is a better candidate, although it seems quite a distance away from the area we might consider Crowpill, even if the area also includes the site of the former Crowpill House. So we don’t have a clear conclusion here.

William of Wembdon’s charter is the only mention of the church of Bridgit in the Bridgwater Borough Archives. The archive is not comprehensive, and the thirteenth century is poorly represented, but if there was an important institution of this sort in the Bridgwater area we might expect at least another mention somewhere. We might expect donations to be mentioned, or at least other property given to it to be mentioned in passing in relation to other properties. As it stands a single meadow is pretty thin, and it is not given to the church, but to the person of the rector, it seems as personal property. It could be all the other property documents do not survive, and by chance none are mentioned in passing elsewhere. Perhaps some fledgling institution failed to take off and was wound up before being mentioned again. After all, although the urban core of Bridgwater of well documented, the periphery has some hopeless gaps: we don’t know the saintly dedication of Durleigh after all. Kidsbury in Wembdon had a field called the ‘Jews Churchyard’, in the medieval period called ‘Euyn Churchyard’, which is hopelessly mysterious.

However, it could be simply that there was never a church of St Bridgit in the Bridgwater area. The church’s rector, Peter has the designation ‘of Bruges’, which could betray this. Bruges was a common rendering of the name of Bridgwater current at the time. A charter of 1245 refers to the town as just ‘Bruges’ (Dilks no.3), another has ‘Bruges Walteri’ in 1260 (Dilks no.8), and we find these two interchangeably used in many documents over the following decades, along with some other delightful forms (eg Bruggewauter in 1295, no.38). ‘X of Y’ surnames emerge in two forms, either someone who owned a place (note Walter of Sydenham in the list of witnesses), or someone who is from a place, now in a different place. Unlike, say Sydenham, for Bridgwater only the latter can apply. If that assumption is taken, then why call someone, who is in Bridgwater, ‘of Bridgwater’? You would not, for obvious reasons.

So we might therefore wonder if this charter can perhaps be explained in the following way: a person, Peter, originally from Bridgwater, has moved elsewhere and become rector in an important church dedicated to Saint Bridgit. Peter has not moved too far away, and still has interest in the Bridgwater area, and so purchases a meadow from William of Wembdon for whatever reason.

Another document in the borough archives, dated to 1322 (Dilks no.94) refers to the church of St Bride’s [i.e. Bridgit] in Netherwent in Monmouthshire. This need not be the same St Bridgit’s mentioned in William of Wembdon’s charter, but it does show that the mental world of the borough archives has further horizons that might be expected.

We will probably never know for certain about this mysterious Church of St Bridgit, but overall:

- it is unlikely there was ever a ‘church’ of St Bridgit in Bridgwater

- there’s a small possibility that it might refer to the parish church of Durleigh

- most likely, in want of more evidence, this refers some church of St Bridgit elsewhere in Britain

Hopefully some further evidence might emerge someday to shed more light on this mystery.

MKP 11 February 2022

Postscript

In July 2024 a copy of Powell’s Ancient Borough was listed on ebay, containing annotations and a paste-in letter by William Greswell (who contributed chapters to the volume). Among these annotations is a note regarding the Church of St Bridgit: ‘later research shows that this church was not at Bridgwater’. We’re yet to find this research mentioned, but it presumably dates to prior to 1920 when the paste-in letter was written (with hearty thanks to Jon White for pointing this out). MKP 8 July 2024.