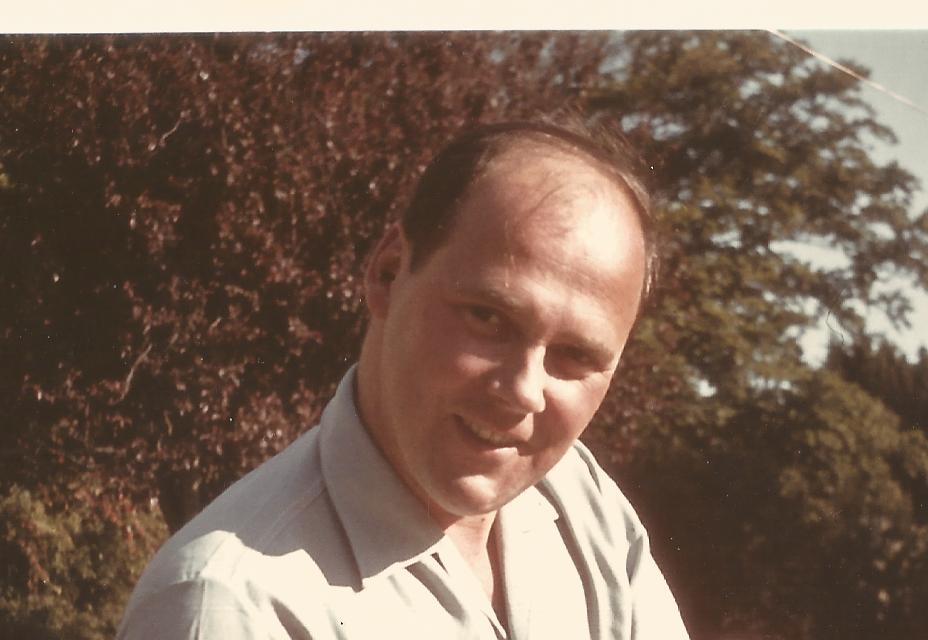

For some 67 years Derek Gibson worked tirelessly for the good of Bridgwater, and his passing on the 1 April 2022 marks the end of career dedicated to good works. A motto he was heard to remark on several occasions was ‘if you want something done ask a busy man’: Derek was both a one-man hive of activity and he got an awful lot done for an awful lot of interests in his 94 years. Derek Gibson has probably done more than any other person to help the interests of the town of Bridgwater, leading the fight for the preservation of the town’s heritage, the enhancement of educational provision and the encouragement of professionals and business leaders to engage positively in the community.

Derek penned a brief account of his professional life in his book A Somerset Architects’ Practice in the 19th and 20th centuries (2007), from which much of this account is drawn.

Full name Henry Atherton Derek Gibson, he was born 24 May 1927 (Empire Day, as he liked to note) in Rumney, Monmouthshire, which at the time was still part of England. Derek’s father Clifford worked as a pharmaceutical salesman, while his mother Dorothy had been a bookkeeper for her family’s mill in Derby until she married. He had two sisters, Beryl and Elaine. Being 94 years ago, this was a different world, being the year the UK was renamed to ‘the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland’, following the independence of the Republic of Ireland; the year of the first non-stop transatlantic flight from New York to Paris, the first traffic lights installed in Britian, the first talking film picture, and, locally, the Bridgwater Pageant.

As with many young boys, Derek had a mischievous streak: he loved pranking his sisters, especially by resting books or containers of water above a slightly open door for them to be hit by, or leaving things in their bed for them to experience as they climbed in. A small child, he was badly affected by hay fever and eczema on his hands, such that he would have his hands bound with cloths trying to stop him scratching. On joining Senior School when other boys left their shorts behind for long trousers, he had to remain in short trousers because he was too small to wear long ones. He did not really grow until he was fourteen, but then shot up. His family were committed Methodists, although he was not especially religious (yet he was always happy to help any church or congregation in need of his expertise, such as helping Bridgwater’s Unitarian Chapel in Dampiet Street).

In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, Derek was conscripted into the Royal Engineers, and served in the Army of the Rhine. On entering the army he had to do his initial fitness twice to allow him to ‘build up’. He was terribly shy as a child and his time in the Army probably changed that: most people will remember a man thoroughly at ease in the company of others. He recounted a couple of stories of serving guard on troop ships returning prisoners of war to Germany: on one occasion the seas were so rough everyone felt ill to the point that another guard was so seasick he had to pass his rifle to a German prisoner in order to vomit over the handrail and then casually took it back afterwards. Derek also commented of extreme cold and ice on a steel ship in the winter of early 1947 that was unbearable for all, including himself, yet (until his later years) he never felt the cold. He also recalled how he and his peers hated wearing the hot, uncomfortable tin helmets and took them off whenever they could. They were building a bridge one day and had just donned the helmets again after a reprimand from an officer, when someone working above Derek dropped a large spanner, which clouted him on the head. He had an almighty headache, but the helmet, now badly dented, undoubtedly saved his life.

Derek Gibson: Architect

Either side of his national service, Derek studied at the Welsh School of Architecture. He qualified in 1951 and attended the Festival of Britain that same year and went to the first concert at the newly completed Festival Hall on the South Bank. He then worked for three years for Sir Percy Thomas & Son in Cardiff, primarily working on large hospital projects. In his younger days he also had a hobby of furniture making, delighting in devising his own designs, rather than working to traditional patterns, to the bafflement of the night-class workshop instructors. He moved to the Bridgwater area in 1954, following his parents who had retired to Goathurst, and worked for a few months for the Borough Architect of Bridgwater. His talents were quickly recognised by the local firm of architects Steer & Shirley-Smith (in 2022 Smith Gamblin), and he started to work for them from 1955, primarily based from Taunton. Derek’s senior at the architectural practice, Robin Shirley-Smith, had a desire that the designs produced by the firm should have some individualist character to them, even within the tight constraints of their clients’ budgets, rather than lifeless blocks. This chimed perfectly with Derek’s zeal for quality, well thought-out design.

He was invited to become partner of the company in 1962, and took over the Bridgwater office in 1967. He served for a time as treasurer and secretary of the South and West Group of the Bristol Society of Architects, then, after it reformed as the Somerset Branch of the Royal Institute of British Architects, he would serve for two years as Branch Chairman. He retired from the architectural practice in 1998. At various times he became very involved with the Royal Institute of British Architects, at times more so than at others.

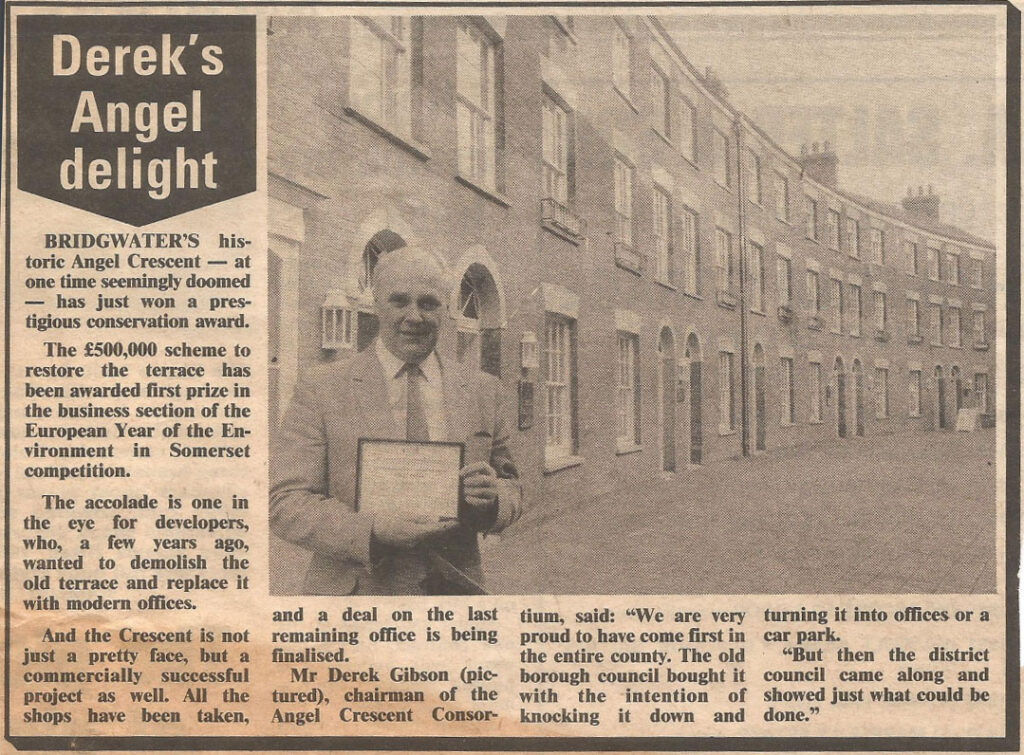

Unfortunately, Derek’s book seldom details which buildings he was specifically responsible for, usually only giving credit to the practice. Only two are credited directly: the first, along with W. John Rigler, Derek was instrumental in the preservation and updating of the curved early nineteenth century terrace in Angel Crescent. Second mention is for his designs for remodelling the library extension at Bridgwater College. Ironically, the college’s ‘Derek Gibson Wing’ was not one of his, but designed by practice partner John Rigler. The wing was named in his honour in thanks for 25 years as a Governor of the college and sometime chairman (more on which below).

Aside from designing private houses, he travelled all over Somerset and did much for the North Devon Health Authority, including Barnstaple, Bideford and Torridge Hospitals. The old Accident Centre in Taunton East Reach was one of his designs – hence demolished – a largely utilitarian concrete construction, the design dictated by the limited funds of the Hospital Trust. He designed a few car showrooms in Taunton, including Autorama in East Reach and Gliddons Peugeot on the other side of town, both now demolished. He did a large number of surveys and recommendations for Churches, primarily for the diocese of Bath and Wells.

Although working for a private architectural practice would have been good work in his early years, as time passed building firms got bigger and had their own in-house Architects. As such, small practices found less work and had to focus on smaller projects and house alterations for wealthier clients, usually individuals. Combined with this, with every recession (there being a total of six in his working career), the building industry went into severe slump, which would have made times difficult. He did not make a lot of money from his work and if he cared passionately about the heritage of a particular project then he probably took the commissions for nothing, or for a hearty discount in the hope of saving it. If he had not been in private practice and not in charge (as a partner) of his own time then he would not have been able to move his work commitments around to pursue his interests. He would often work Saturdays and occasionally Sundays to keep up. If he went on holiday then he would work late every evening to get ahead, for at least two weeks before and again after his holiday.

Although Derek was a tireless advocate of the preservation of historic buildings, he was not a revivalist when it came to architecture. He held the principle that buildings should reflect their own times, and not be a parody of past styles (especially as modern attempts to copy past styles usually always fail to match the quality of the originals). This he made known to the local planning department on several occasions, as this extract from a public planning consultation illustrates, with his distinctive style:

“With all due respect to [the District Council’s Planning Department], I can only take the view that these planning officers, having no architectural qualification have been doing their best merely to minimise the effect of a badly conceived scheme, rather than press for a design which would be more in keeping with the 21st Century, rather than being one as a mere poor pastiche of past architectural styles.

“Over several years when writing on behalf of the Civic Society, I have consistently expressed such comment, but the Council appears to be incapable of striving for a forward-looking view as to development in our historic town! I feel sure that my colleagues (including Councillors from the three Local Authorities) serving on the Bridgwater Heritage Regeneration Partnership, chaired by myself, are unanimous in seeking the best in respect of built changes to the Conservation Area. WE, and Bridgwater townsfolk, MUST NOT BE LET DOWN. !

“In expressing my opposition to current proposals, amended or otherwise, in its present form, it is suggested that the applicant and/or his/her Agent be urged to seek proper architectural advice as to redesign. A redesign must of course have respect for the appearance and architectural character of the immediate area, which in general undoubtedly requires enhancement, but does not need to falsely replicate same.

That said, above all else he held the view that any development should be sympathetic as possible to their historic surroundings: modern but respectful.

One building in Bridgwater, if not designed directly by Derek, certainly holds to his principles and designed by his office, is the Riverside office at the end of West Quay, which was built for Summerfield Developments Ltd. In the 1980s. Certainly a modern building in materials and feel, yet it remains in keeping in terms of its restrained form, massing and occasional detail, so it places well within the historic riverside frontage. Such is the success of this building it is seldom noticed: it does its job admirably.

Arts Centre, Round Table, Rotary, College

After his move to the Bridgwater area, Derek became active in societies associated with Arts Centre in Castle Street, and for a time also served on its management committee. He was involved with the Amateur Drama Group and the Blake Drama Club, even playing the lead male role in J.B. Priestley’s ‘They came to a city’, which played in the Town Hall. This theatrical side would occasionally shine in later years: he and Jack Hall teamed up to do a Flanagan and Allen tribute act when Bridgwater Rotary used to stage concert shows to raise charity funds at Haygrove School. He had a lifelong love of radio, especially BBC Radio 4.

Through the Arts Centre he became acquainted with John Allen (1929-2017), his first close friend on moving to Bridgwater. John would recall to Derek’s son Nick how Mr Gibson once owned an Austin Seven, his first car. One time the two were driving near Goathurst (where Derek’s parents lived there at the time) and, being sometimes something of a fast and furious driver in his youth, Derek managed to drive them into a ditch, fortunately without major harm.

It was John who introduced Derek to the Bridgwater Round Table, beginning a major stand in Derek’s life, of civic-minded and charitable activity. After 12 years, in 1968 he left the Round Table, and was invited to become a member to the Bridgwater Rotary, which became one of his great passions. Rotary’s motto is ‘service above self’ and Derek certainly held this ethos dearly. He was part of a culture where by professionals and business leaders felt it their responsibility to positively engage in the civic life of their communities, a philosophy which has been in sharp decline. He was twice president of the Bridgwater Rotary Club, and would become its longest-serving member.

Derek was a member of Bridgwater Rotary for 50 years and served twice, at some time apart, as President. Derek and Andre Grant were the driving force and mentors in the formation of the daughter club, the Sedgemoor Rotary Club. He briefly served on the District Executive in the 1970s and was even nominated for District Governor, which he ultimately declined to take on. Derek was part of the initial team from Bridgwater that went over to Salzgitter-Wolfenbuettel in Germany (not far from Brunswick where he had served in the army after the war in 1947/8) on a fact finding mission in 1981, regarding the establishment of a link with the Rotary Club there. Derek was often referred to in the Bridgwater Rotary Club as Mr Salzgitter-Wolfenbuettel while his counterpart in Germany was referred to by his club as Mr Bridgwater. Fellow Rotarian David Gwilliam, who had been introduced by Derek to Rotary in 1974, recalled the following:

In 1982 four Rotarians from the Bridgwater Club, John Paterson, Tony Chapman, Derek Gibson and I, visited Wolfenbuttel, Germany, to see if a friendship could be created between our two clubs. We hired a car which Derek drove as he could speak some German, and had some knowledge of the area, having been stationed in the region when in the army. Being an architect he wanted to show us the unique designs of the roofs, gables and chimneys in a historic town. This meant that we had to lean against the windows to admire them as the car did not have a sunshine roof. Derek’s attention was diverted from steering as we drifted to the British side of the road rather than on the right side that Germans prefer. In spire of flashing lights and horn blowing it took some time for Derek to get back to the right side of the road which was German friendly. Fortunately it was a relative quiet road and there was no collision. Three of us decided that, from then on, we would ignore German roof designs.

The Salzgitter-Wolfenbuettel Rotary would honour Derek twice with a Paul Harris Fellowship, to which he added two from the Bridgwater Rotary. Derek was committed to raising money for PolioPlus, Rotary’s campaign to eradicate the disease, being prompted by the example of his inspirational (in Derek’s own words) nephew Howard, who had polio as a child. Derek would regularly be seen at Carnival time, collecting donations for Rotary, all the way into his eighties.

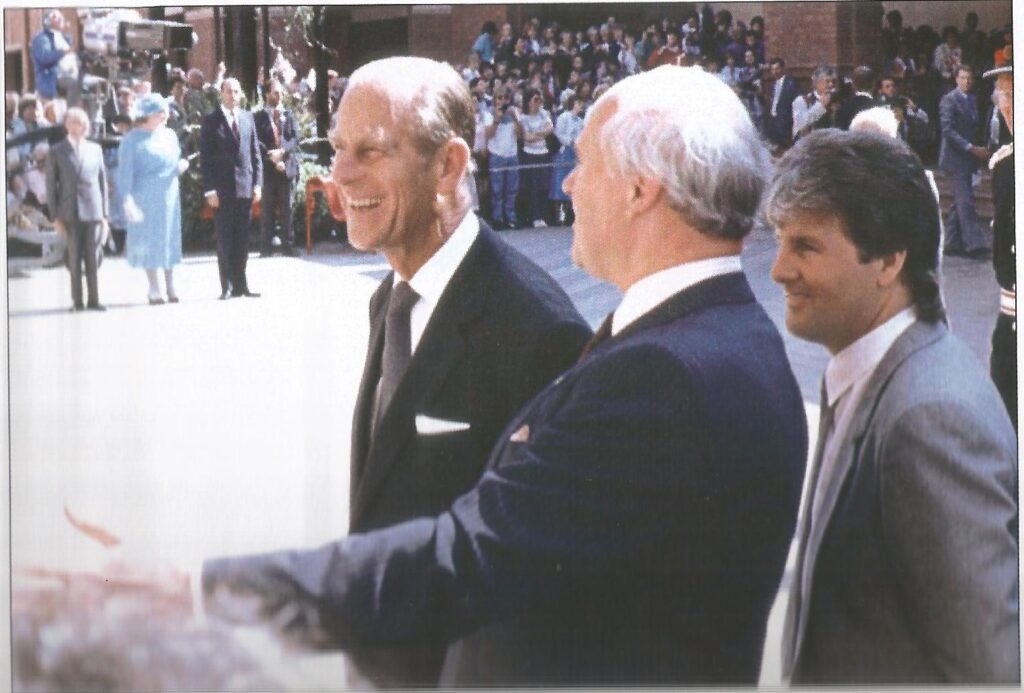

In 1972 Derek was nominated by the Bridgwater Chamber of Commerce and Shipping, to serve on the Board of Governors for the Bridgwater Technical College, which would later morph into Bridgwater College. Derek would play a leading role in organising the opening ceremony of the Bath Road campus. He retired from the Board in 1997, a wing of the college being named in his honour in hearty thanks for his service. In later years, Derek had great satisfaction in the 2016 takeover by Bridgwater College of the struggling Somerset College at Taunton, especially as the Taunton colleges had usually looked down on their Bridgwater counterpart over the years. For more than twenty years he was also a governor of Haygrove school.

Bridgwater and District Civic Society

One of the great achievements of Derek’s life was the creation in 1971 the Bridgwater and District Civic Society, and his stewardship thereof, has done important work in the preservation of the town’s heritage. The 1960s had seen the wrecking ball very active in the town, seeing whole sections of the town centre wiped off the map, West Street and Binford place being two in 1966, the wasteful totem being the loss of the beloved George Williams Memorial Hall, i.e. the old YMCA building on the corner of Eastover and Salmon Parade in 1968. In a short decade the character of the old market town and port was irreversibly changed for ever. Derek was summoned to the Mayor’s Parlour in the Town Hall and requested by Mayor Irene Tester, to form a Civic Society in the town. Not only was the group successfully formed, Derek secured Lady Gass as honorary president. The society was able to make representations on planning matters, especially on listed building consent. Although there have been notable set-backs over the years, and many a fine building lost, much has been saved, preserved and its future secured through the society’s efforts.

He had little sympathy for the workings of the planning apparatus of the district council, where by carpet-bagging officers and out-of-town councillors could wield so much power over, having little interest or connection to the town, and Derek often resented the fact that senior officers often lived a considerable distance from the town and sometimes even the district. In politics he was mostly unaligned, usually trusting on the calibre and integrity of the candidate over which party they belonged to. He mentioned once his intention to spoil his vote on the grounds that none of the candidates in the national election had bothered to canvass, thinking this a shameful dereliction of duty. Prior to the 1974 he served as a councillor for the Langport Rural District Council, ultimately becoming Chairman of its finance committee. However, with the demise of the council that year and the creation of Yeovil District Council (later South Somerset), he stepped down, not liking service based on allegiance to political parties, which would have been necessary to be a councillor in the new district. He was sometimes unreserved in his criticism of politicians, such as when the District Councillors granted themselves a pay rise in 2018, in the context of cut-backs and staff redundancies:

“Politicians leave themselves being accused of ‘money-grabbing’ with expensive costs to our community, regardless of actual achievements gained both as individuals and collectively. Where is their Sense of Voluntary service, FOR WHICH THEY WERE ELECTED TO SERVE? They should not expect grandiose expenses, but only sums in genuine recompense for actual achievements. Councillors should set a good example to their constituents, by illustrating their actions as setting a high level of LEADERSHIP. We do not see such!’

Through the Civic Society, Derek would also become involved with the Campaign for the Preservation of Rural England, the Somerset Building Preservation Trust, and the Halswell Park Trust, which he also served for a number of years as chairman. This Trust has done much to preserve and enhance the historic parkland and the Temple of Harmony, which is in the Trust’s custodianship. He helped in the inaugural meeting and discussions that formed the Friends of the Wembdon Road Cemetery in 2010, offering valuable advice in its early formation and raised funding for the repair of the Arthur Cottam memorial, father to one of his predecessors in the architectural firm, and a noted astronomer.

Under Derek, the society achieved some noteworthy, but underappreciated projects, such as the restoration of the Victorian lanterns to the town bridge, features taken entirely for granted now. The riverside would also see the restoration of one of the town’s mechanical cranes. In terms of heling public engagement with the town’s rich history and heritage, the society would publish Jack Lawrence’s Town Trails. In 2008 the town would see the installation of cast-iron blue plaques, supplementing earlier efforts of information plaques on the Unitarian chapel and at Castle Street. However, it was Derek’s representations on behalf of the society on planning matters where his efforts were primarily focused, making the most of his architectural expertise, intervening where planning applications might harm a listed building or its context. Part of this effort also saw his work as representative of the Civic Society on the Bridgwater Heritage Regeneration Partnership, challenging and thankless position as the unpaid consultant and campaigner, sometimes leader, of a committee of representatives of Sedgemoor District Council, Bridgwater Town Council and Somerset County Council.

In 2012 he was awarded an engraved crystal glass bowl on behalf of the Civic Society, bearing the message: “Bridgwater & District Civic Society: Award to H.A.Derek Gibson MBE in appreciation of his 40 years continuous service 1972-2012.”

Over the Summer of 2006, while volunteering for the Civic Society I had the great pleasure, along with Bernice Lashbrook, of helping Derek catalogue a huge collection of architectural drawings, ranging from 1837 to 1985. Working in a former pig shed, Derek would unroll each drawing to inspect and comment, while Bernice would diligently write up the catalogue entry, then finally I would string up the roll and write the ‘HADG’ reference number (which were subsequently ignored by the Heritage Centre). Occasionally Dr Peter Cattermole would pop in to supervise. The best part of this process was that each day Derek would lay on both a hearty al fresco lunch in his beautiful gardens, and idyllic weather. Derek always liked gardening and having a vegetable plot and grew a lot veg and some fruit. For a while he kept ducks (for eggs) , he always liked duck eggs. He and Olga won awards in the Cossington in Bloom competitions.

This archiving work led to an exhibition in St Mary’s Church in the following Spring, and the publication of his book, mentioned above. In this book Derek described the history of his firm, but also gave a full account of his professional life, along with a brief account of his civic activities.

As well as the many great achievements, it’s also the failures that speak to the spirit of the individual. In the early 2010s Derek put considerable effort into having a walkway erected along the Durleigh Brook from the bottom of Blake Street through to St Mary Street. The thinking being that a routeway here would encourage footfall for the Blake Museum, but also provide better access to the Town Centre. Considerable progress was made in the project, but after many, many months of work, a single road-block prevented it going forward, and it had to be abandoned. Aside from the occasional sigh, Derek was always philosophical about the setback, it was just one of those things.

The last project I worked with Derek on was the preservation of the Castle Watergate on West Quay. Neglected for some 800 years, when the British Archaeological Association visited Bridgwater in 1856 it lamented the poor presentation of the Watergate, the oldest and most important historic structure in the town, and called for its better preservation and presentation. Absolutely nothing was advanced for 150 years, until Derek intervened with the developer in 2016. Derek worked closely with the new owner to ensure the best conservation arrangements for it and the adjoining listed buildings. Part of the project was the installation of an interpretation panel (the part I was involved with). This architectural and historic conservation consultation work, providing invaluable expertise to the developer, was done gratis, underlying Derek’s commitment to the town’s heritage. It has been commented that his enthusiasm and unselfish support of good causes could be to the detriment of his architectural business.

Derek Gibson, MBE

In 2010 Derek was awarded an MBE in recognition of his tireless work for and around the Civic Society, Rotary and Bridgwater College. This was just recognition for a lifetime of service (he also joked to his family that MBE stood for ‘My Bloody Effort’, whereas OBE was Others’ Bloody Effort). His statement for the Bridgwater Mercury (5 January 2010) is characteristically understated:

‘It’s nice to receive recognition and I feel very privileged. I am still heavily involved in the community. I am trying to get a walkway built between St Mary Street and Blake Street and I will shortly be making a planning application, and I am trying to achieve a new village hall for Cossington and things are looking positive. I think I am most proud of my work in progressing the civic society and I now have a great team behind me and we have managed to get a lot of young people involved.’

The last mention to Cossington village hall was a project he took on after moving their on his retirement. He arranged negotiations with Strongvox Houses (which were built) to provide funding for a new Hall, with the land donated by a farmer. He then spent much time on site as Project Manager. The foundation stone was laid in 2011.

In 1958 Derek married Olga Warren, a solicitor, and they had one daughter, and three sons, twins Julian and Nicholas, Fiona and Timothy. Deepest sympathies are expressed to the family on their loss.

Derek’s absence from the civic life in the old town will be felt for some considerable time to come.

MKP. With sincere thanks to Nick Gibson, Kate Ness-Pomroy Ute Smeed, Bob Gordon, Bernice Lashbrook, Tony Woolrich, Phil Maye, David Gwilliam: any further additions and anecdotes are welcome.

It seems appropriate to round out this obitury and let Derek have the last word. The following is an edited text of a talk he gave to the Bridgwater Rotary on 21 July 2014:

WHO & WHAT AM I: A verbal ramble.

I told Secretary Dick that I had never been asked, as was custom for new Rotarians to give a ‘My Job’ talk. In early membership days, maybe my subsequent role of Speakers Secretary for a few years (50 a year) had me ‘overlooked’, so here goes.

I start with the subject of death, which will meet us all at some undetermined time, & its ‘afterlife’. Church tutors, bible bashers and hot gospellers throughout the ages have addressed the populace about heaven & hell, all probably fully believed in what they said, teaching even today that our soul leaves our body after death, and we should meet our dead ancestors in heaven, How do we know? No-one has returned to confirm that on which we have been brought up. Nevertheless, with such in mind, I have often thought that the souls or spirits of our dear departed are perhaps regenerated in our offspring, and incidentally I can clearly see certain traits of behaviour of my late father in one of my sons born after his death. But such is hearsay or conjecture with no scientific backing, with respect to our religious leaders of whatever sect. But in the 20th and now 21st century, any such suggestion of inheritance can likely be traced in our genes, putting aside more recent DNA science. So, I have asked myself: “Who and what Am I” ?

Some research into one’s ancestry gives some clues as to who I am, in what I take interest , and what activities have occupied my life.

Firstly my working occupation: Architecture. My father, according to my mother’s report, originally wanted to be an architect, but parental control at the start of the 20th Century declared that he should not so choose, as a then local architect was quoted by my grandfather as being “as poor as a churchmouse” – I sympathise! Such prompted Father to say ‘Derek should be allowed to do what he wants’, noting at the time that my maternal grandfather offered to finance me through medical school training.

In days of my boyhood, it was commonly said that boys wanted to be engine drivers. Not me. I recall as a young lad spending endless hours watching bricklayers build a high boundary wall around a local Childrens Home: such nurturing my early interest in construction. But genes are possibly in evidence, as my father’s grandfather was a bricklaying builder, according to past Census returns. So I eventually undertook a full-time College course, of five years, interrupted by three years of conscripted army service, finding such ending in Germany in 1948. My graduation was celebrated with a fellow student by a week’s visit to London for the 1951 Festival of Britain, so gaining an exciting delight in the enterprising design on view and the promises shown for Britain’s future. I have always been conscious of professional ethics of behaviour, and the training that an architect has two main responsibilities: firstly to one’s client for whom one attempts to design not a mere box of a building, but one of well considered design, with interiors being fit for purpose, and hopefully stimulating in appearance. Secondly an important responsibility for an architect is not to ignore the effect of one’s design on members of the community and the building’s environs.

Secondly my public service. When living near Ilminster, with a vacancy occurring in my village, I agreed to be Parish Chairman, with subsequent election to serve independently on Langport Rural District Council in 1960s. Following local government Re-organisation in 1974, I had no time to become involved in party dominated politics on the larger Councils, but have continued to taken a strong interest therein on a strictly non-party basis. Have my interests been engendered by past ancestors? Limited ancestral research has established that a Thomas Gibson, a weaver by trade, was Mayor of Lancaster in 1745. Such being a prominent historical date, the Record Office at Lancaster confirmed that there was no mention of any link with Bonnie Prince Charlie of the Jacobite rebellion, who marched south through Lancaster as far as Derby. Had he, of Scottish descent, been supportive of the Scots? Thomas was subsequently elected as a Freeman of the town. Separately my mother’s father, who owned tape weaving mills, was Mayor of Derby during the first world war, but refused to be nominated for election to serve in Parliament. He died in 1945 aged 93 and never retired!

I have never been afraid of speaking my mind, including being accused of soap-boxing! A past ancestor spoke up in Lancashire for a wider public suffrage in the 19th century, when only men of some property owning stature were entitled to vote (Long before the suffragette movement emerged). He was tried & condemned to be transported to Australia, firstly being held on hulks in the Thames estuary prior to his deportation. Upon returning to England in later years, he was again accused, but one could not then be tried for the same offence, and I have a lengthy newspaper report of the time concerning same.

Maybe my willingness in becoming involved in the community commenced following my arrival in Bridgwater in 1954; and seeing the nation’s first Arts Centre in the town, I became involved in its committee work and drama activities, developing separately with Blake Drama Club and ‘starring’ in the leading role in a Town Hall presentation. Longer established Rotarians will be aware of my saying that I am always ready to make a fool of myself, as witnessed by my enrolment by Jack Hall in his arranged Members Entertainment evenings. I cannot point to any ancestral involvement in theatricals which could have so influenced me, but willingness to address and appear before assemblies could be attributed to the fact that both my grandfathers were lay preachers in their respective chapels.

Certainly, however, my early experience as a Bridgwater Round Tabler locally, at Area and National level, did a lot to influence my then future 47-year life in Rotary, and in my personal voluntary services to the community, which activities I believe can be regarded as an extension to a rotarian’s service commitment with their Club… Incidentally, we are now hearing much of the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow, which I have visited only once when a Round Table National Councillor, when Devon & Cornwall NCs and I hired a car for a day to tour around Loch Lomond. I am proud of my Scottish ancestry, being part of the Buchanan Clan.

Certainly my service in the South-West & in Somerset to my professional institute and its activities, prompted the Borough Mayor to invite me to found the Bridgwater and District Civic Society in 1972, and active involvement in several environmental bodies has continued to this day, as a result thereof.

Finally, I conclude with a mention of research results into National Census returns of the 1800s, which disclose ancestors with very much a background of trade and craftsmanship. Occupations include a cooper, a weaver, and shoemakers. A 16-year old Cordwainer, a grocer’s assistant, a Land Surveyor, in 1901 a Steam Engine Maker, & an engine smith. A Book-keeper, a 19 year old Iron fitter’s apprentice , not to mention a railway clerk and a Goods railway clerk. So it can be gleaned that there are no ‘silver spoons in mouths’ as far as my ancestry is concerned. Maybe in my life, some may consider that I have just been ‘playing the fool’ ? But, I conclude in response: I AM JUST AN ORDINARY BLOKE.