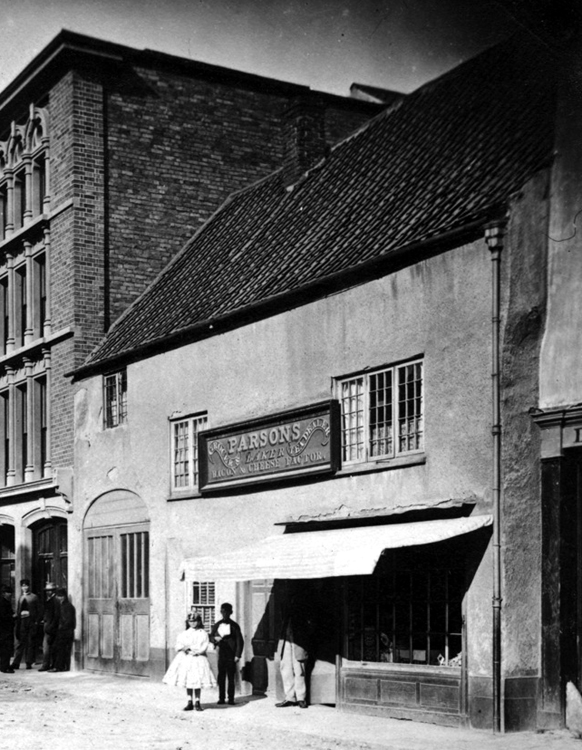

Although an unassuming building from the street front, it contained some of the richest treasures from Medieval Bridgwater, the Bridgwater or Burrell Ceiling.

Little is know about the history of the property. It was owned by the Town Council from at least 1762, when it was leased to Joel Quarrel, a malster. In 1823 it was leased to John Nicholls, a linen draper, and in 1835 it was occupied by Charles Foster and James Dare.

In the 1881 census the property was called ‘the Dining Rooms’. It was evidentially an ample enough building, as in 1911 the number of rooms, including kitchen, but excluding scullery, landings, lobbies, closets, bathrooms, storerooms, offices or shops, extended to 16 in total. The census reveals that there were usually six or seven people living in the property.

Robert Pitman acquired the property sometime between the 1871 and 1881 census. He had been born in Bridgwater in 1857. Over the decades he was described as a confectioner, baker and shopkeeper. He died in September 1935, aged 78. His obituary described his love of fishing, shooting and rugby (Taunton Courier, Wednesday 11 September 1935). It was Pitman who made an amazing discovery in this property, but also led to its demolition.

The Bridgwater Ceiling in the Burrell Collection, Glasgow

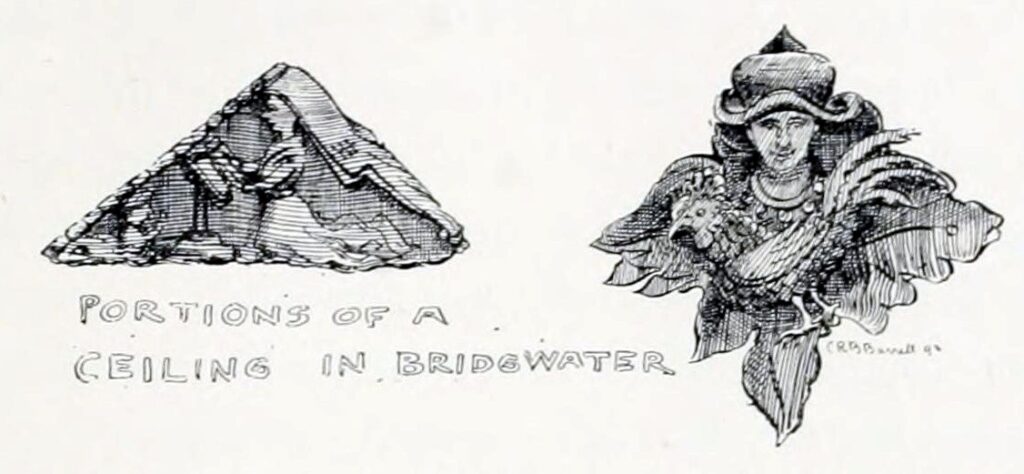

The local story goes that when Pitman was cleaning the ceiling plaster in the ground floor in advance of whitewashing, a hole made in the plaster revealed a piece of carving. Over many months, maybe a year, he chipped the rest away to reveal a wonderfully ornate carved medieval ceiling. The first datable mention of the ceiling seems to be by C. R. B. Barrett in 1894, who visited Pitman’s ‘refreshment rooms’ and wrote of the ceiling, meaning that it was found sometime between 1871 and 1894 (C.R.B. Barrett, Somersetshire: Highways, Byways and Waterways (London, 1894), 260-261).

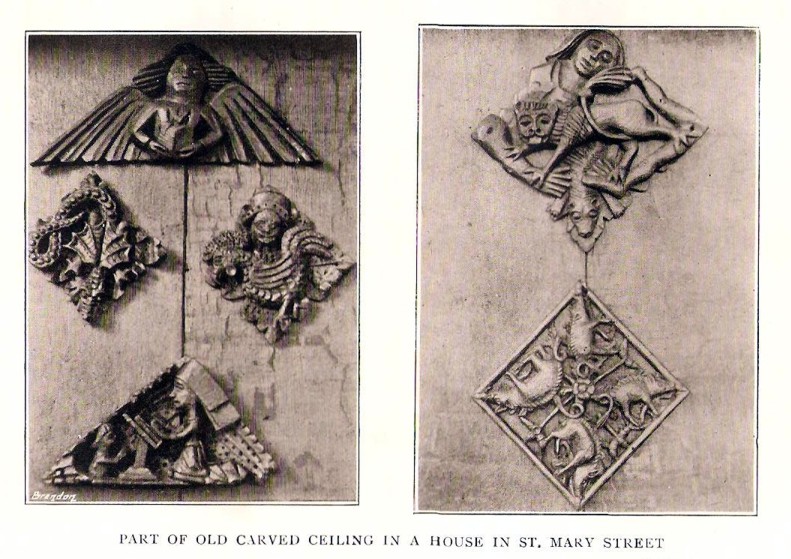

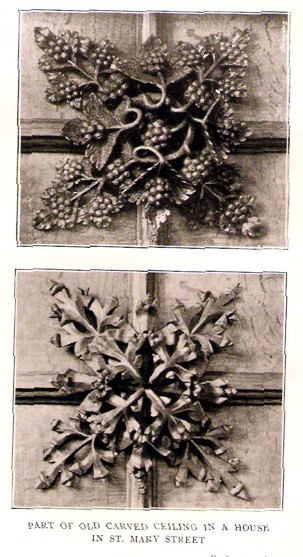

The Bridgwater Ceiling consists of 16 panels, with 415 ornamental carving in total and 25 moulded beams. C.R. Barrett, who saw the ceiling in 1894 reported:

‘In a house at the east end of the churchyard, now used as a refreshment rooms, there is a very remarkable ceiling, from which I derived the two details here illustrated. The ceiling has twelve panels, divided by massive, well-moulded beams, and decorated with very quaint bosses. My sketches show two of these, and most remarkable of the remainder have for their subjects four pigs or boars intwined, a tomfool, an ecclesiastic and a lion, a demi figure clutching a fiend, and an animal devouring grapes. Behind some matchboarding, which has quite recently been nailed onto the staircase, I was told that some beautiful carved windows exist, but I suspect that these windows are in reality the remains of a screen.’

The inclusion of a Tudor Rose (assuming that it is contemporary with the rest of the ceiling) in the decoration means that it was made sometime after 1485, and it would presumably have been made before the Reformation of the 1530s.

In the late 1920s Pitman sold the ceiling, and several other architectural fragments from the house, to American newspaper tycoon, William Randolph Hearst. Hearst’s collection was broken up on his death, the ceiling being in storage at the time, when it was then purchased by Sir William Burrell a shipping magnate turned art collector, in 1952. Since 1981 the Ceiling has been on display in Glasgow’s Burrell Collection.

The ceiling was an integral feature of the Cupola: indeed, after the ceiling was sold by Pitman the upper floor became dangerously weak. Pitman sold the property to the Bridgwater Town Council in 1932 and they demolished the building that year. However, although the ceiling was integral to the house, it was not necessarily built for it.

The Bridgwater Screen at St Donat’s Castle, Glamorgan

Also sold by Pitman to William Randolph Hearst was a carved medieval screen, 18 foot wide and 7 and a half foot high; also a heavy oak column and window frame. What became of the latter two is unknown. Hearst had the screen incorporated into the end of the dining hall at St Donat’s Castle in South Wales, his home while visiting the UK.

The ceiling and screen salvaged from the Cupola all look to be ecclesiastical, rather than domestic in origin, presumably salvaged from a church when the house was built. They may have come from the Franciscan Friary, which survived into the 1640s, the Hospital of St John in Eastover, the Chapel of St Mark in Bridgwater Castle, or perhaps from a side chapel within St Mary Church.

Research on the ceiling continues.

References:

Papers relating to the Ceiling in the Blake Museum, Bridgwater.

Robert Dunning, Bridgwater History and Guide (Sutton, Stroud, 1992)

M. Adams-Acton, ‘Structural Ceilings of the Early Tudor House’ in the Connoisseur (1949) pp.75-82

Robert Dunning, ‘Bridgwater: Churches’, A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 6: Andersfield, Cannington, and North Petherton Hundreds (Bridgwater and neighbouring parishes)(1992), pp. 230-235.

Jack Lawrence and Chris Lawrence, A History of Bridgwater (Phillimore, Chichester, 2005)

Arthur Powell, Bridgwater in the Later Days (1908) p.41

Miles Kerr-Peterson 25 September 2020