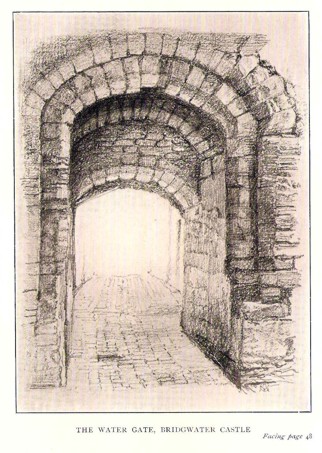

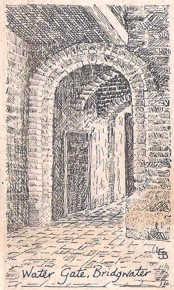

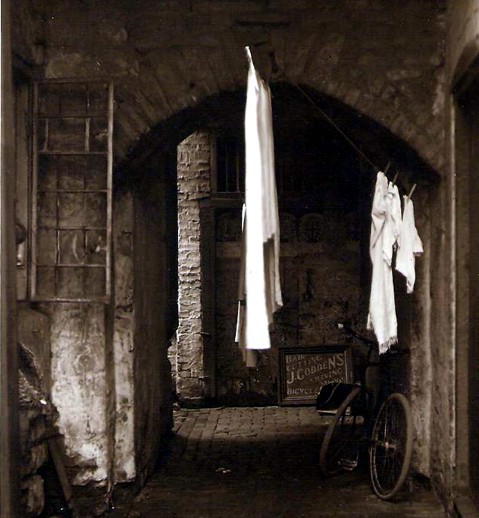

Attached to the West Quay Wall and tucked in a little alleyway between the former Westgate Hotel, on the left, and a former bank, on the right, is the Watergate of Bridgwater Castle. This is a triple Romanesque-arched gateway, which can be dated to the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries, and gave direct access to the castle from the riverbank quay.

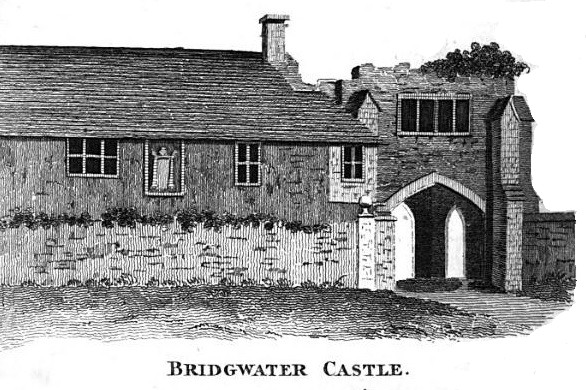

The Watergate is apparently depicted in an illustration labelled Bridgwater Castle, published in the Topographer magazine in 1790. [1] It is hard to recognise the Watergate as it appears today, as it has pointed gothic arches (rather than the round Romanesque arches it really has) and much larger size in relation to the adjoining building. In 1791 the antiquarian Collinson recorded that the only parts of the castle remaining are the ‘water-port and some ruins of the lodge’.[2]

The answer to this is that this illustration is not of Bridgwater Castle. It is Taunton Castle, and based on an illustration by John Inigo Richards of 1752, which can be seen here.

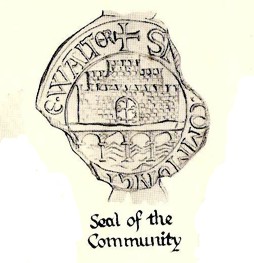

The two seals of medieval Bridgwater, if taken at face value, might be interpreted as depicting the Watergate and an approximation of the eastern wall of the castle and quay. The rounded arch, the round towers and the quay to the front certainly corresponds with the archaeological evidence, although we should expect the view to be simplified and stylised. The older seal of the fourteenth century depicts an elaborate doorway with decorative ironwork hinges, with bold scrolls in the shape of a ‘C”. The later seal of c.1450 shows a portcullis.

Description

The arch closest to the river has been very badly reconstructed in sandstone and brick at some point in the nineteenth or very early twentieth centuries, possibly when Sealey’s bank was constructed, as its quality is far inferior to the wonderfully carved arches within.

Between the two arches further from the river is a large gap which served as a murder hole. Below layers of render, paint and accrued pollution the Watergate is made entirely in handsome golden yellow Ham stone.

Within the Watergate there is an alcove on the northern side, presumably for a steward or sentry. From the look of the surrounding stonework this seems to be contemporary with the original design.

Recent resurfacing of the lane revealed that the ground surface at the Watergate has not really risen over the centuries, so its current height is approximately original. There survives, or there is evidence for, a number of iron pintles, which can be found in the stone work in the jamb below the outer arch facing the river, as well as within the structure in front of the rear arch.

From these we might conclude the existence of two sets of doors. One set was contained within the Watergate, just in front of the innermost arch. Directly in front and above these doors was the murder hole above. The second set of doors was set at the very front of the Watergate towards the river and quay. The appearance of these doors is suggested on the earlier seal of the fourteenth century.

Directly in front of the Watergate towards the river set into the ground are two projecting Hamstone blocks, which have square pockets, which have been interpreted as being for the receipt of a portcullis. These two stones differ in shape and detail of design. Examination of the south block showed that it is clearly separated from the surrounding stone on the west. There is no trace of mortar on the upper surface. It seems likely that this block was inserted below the existing masonry. Within the pocket (2.75in x 2.5in x 1.5in deep) at the west end there is a number of indentations, but the remaining base of the pocket is smooth. There is no sign of any metal or lead. The north block seems to have been fabricated by a different mason. It is of different shape to the block on the south. The pocket is more rectangular (2.75in x 2in x 1.125in deep). At the front edge there is a single depression on a flat base. There is no trace of mortar on the upper surface. This block may have been inserted, like the south block, but it is not as obvious.

Although the outer arch has been badly reconstructed there is evidence that this might have once been two arches, a solid one attached to the main body of the Watergate and a detached outer one as suggested by the surviving springer stones. Presumably this enclosed the portcullis.

A possible interpretation for all of this is that the Watergate originally consisted of the three main round arches containing two sets of doorways. If the heavy outer doors were breached, a second inner set was protected by a murder hole above. Sometime later, and it seems in a hurry, a portcullis was attached to the front of the structure and an additional arch was added to enclose this.