The High Cross was located at the top of the High Street, roughly in front of Lloyds bank, straddling the current road. Crosses denoted places of controlled trade and the area of the Cornhill was the site of Bridgwater’s principle medieval market. Crosses were often grand and elaborate as they expressed a town’s pride and prosperity from trade. The area of this market was probably much larger when the town was initially laid out around 1200, but was subsequently encroached upon with buildings, the Cornhill market house possibly covering this area.

The High Cross itself is first mentioned in 1367 although with the existence of a market it is likely that a cross stood much earlier than this. It was extensively altered and rebuilt in 1567 to create the structure recorded by John Chubb around 1800, described below.

In 1764 a description of the town mentions: ‘there is a spacious Town Hall and high Cross, plain but in good Repair, and over it a Cistern, to which Water is conveyed by a Brook by an Engine fixed in that formerly called the Queen’s Mill, and from this Cistern, it is carried into most of the streets’, Philip Luckombe, The Beauties of England, 1764, p.34.

The High Cross, also known as just ‘the market’, was specifically earmarked for demolition in the 1779 Act of Parliament for erecting a new market house in the town (what would become the Cornhill Market House). This was to improve access to the new market building: sadly this would not by any means the last time a piece of the town’s heritage was sacrificed to help ease congestion. It did however survive for a few decades more: William Baker, writing in 1851 thought it had been demolished only fifty years before.

From Pooley, C., The Old Stone Crosses of Somerset, London: Longman Green & Co, 1877

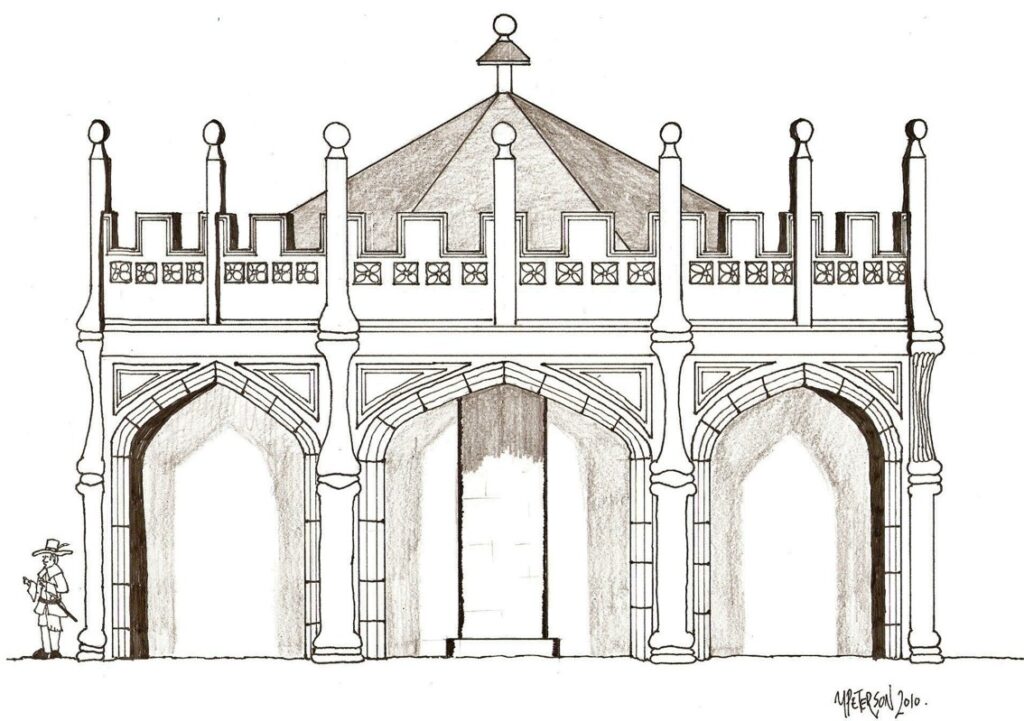

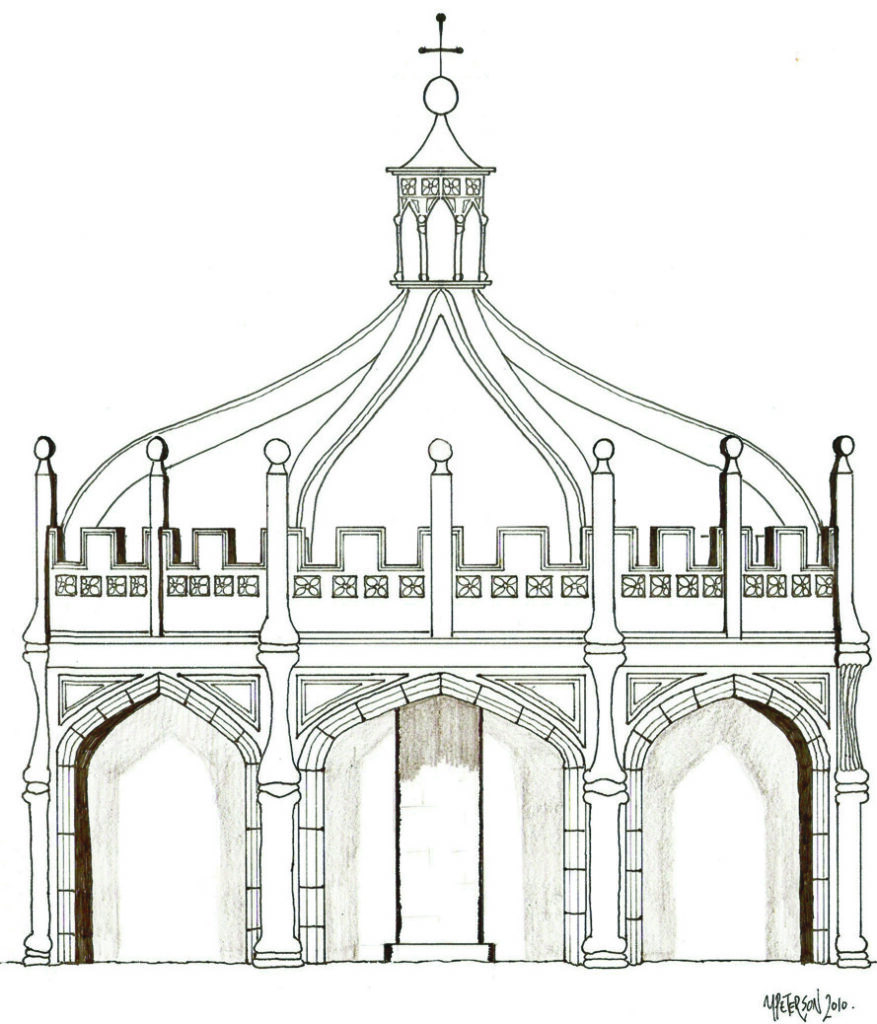

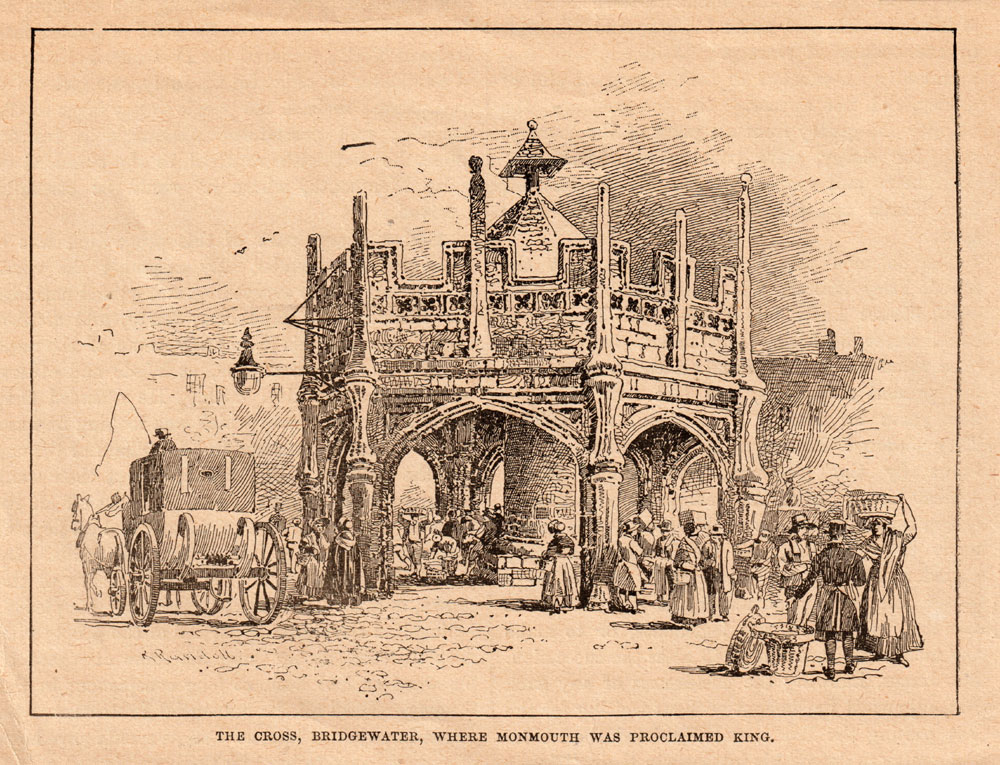

“The site of the High, or Market Cross, as it went by both names, was on the Cornhill, opposite to the entrance to High Street. It was an octagonal building in the Perpendicular style of the late Fourteenth century, constructed of eight obtusely pointed arches springing from lateral piers, and a central pillar supporting a roof, round which ran a very deep embattled parapet pieced with quatrefoils, and ornamented with pinnacles, at the angles and centre of each face. The horizontal mouldings were vigorous, as were those which adorned the spandrel spaces, and the curved faces of the arches.

“It was surmounted by a sort of dove-cote construction which, together with the roof and upper part, were modern. Probably the central pillar was carried up, in the original design, two or three tiers higher, and finished with canopied niches and sculptured and pinnacles, in harmony with the style of architecture of the base.

“The Cross was used as a market-place for the sale of many articles, especially of fish, and exhibited on one of the pillars the appropriate admonition “MIND YOUR OWN BUSINESS”. In the reign of Janes II, a grant was made to supply the town with water, and a tank was accordingly erected on the building, which, being filled by an engine from the Queen’s Well, was thence distributed to the town. The Cross was pulled down about fifty years ago. From the High Cross public addresses and proclamations were made; to wit, the proclamation of the unfortunate Duke of Monmouth as king (in 1685) by Alexander Popham, Esq., the then mayor of Bridgewater, who on the occasion was accompanied to the Cross by the burgesses in their robes of office.”

Important proclamations were read out at the High Cross, presumably by standing on top. Here’s is John Oldmixon’s (1673-1742) account of the proclaiming of Monmouth King in 1685, in his History of England, during the Reigns of the Royal House of Stuart, published in 1730:

The Duke, after he was proclaim’d King at Taunton, march’d to Bridgwater, eight Miles distant. He had then with him the greatest Number of Men that ever were for him together, near 6,000 tolerably well arm’d. He was proclaim’d in this Town at the High Cross by the Mayor Mr. Alexander Popham, and his Brethren in their Formalities. Here his Declaration was read, and the Inhabitants with a sort of Emulation who should do most, sent all kinds of Provisions to the Soldiery in a rude sort of Camp in Castlefield near the Town, where six Regiments of Foot appear’d, distinguish’d by their Colours, and had the Face of an Army. … The Duke’s Quarters were in the Castle, where King Charles II and King James II at several times had also their Quarters. Here he rais’d more voluntary Contributions than in any other place, by the Management of Mr. Roger Hoar, Mr William Coleman, and other Inhabitants, great Friends and great Suffers for this cause, a very unaccountable one indeed at that time.

References

Lawrence, History of Bridgwater, (2005)

Powell, Bridgwater in the Later Days, (1908)

Dilks, Bridgwater Borough Archives 1200-1377, (1933)