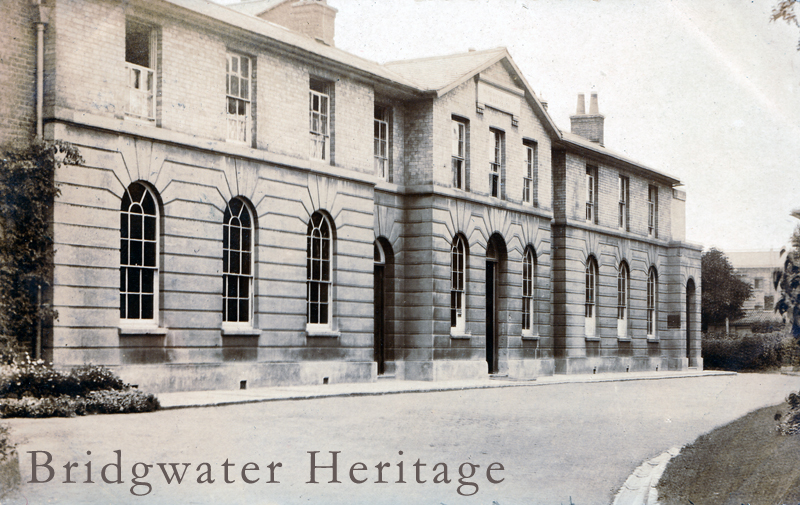

Northgate Union Workhouse Built 1836, operating by 1837 and demolished late 1970s (precise date TBC)

Background

After the dissolution of the medieval monasteries and chantry chapels by Henry VIII in the 1530s (such as Bridgwater’s St John’s Hospital), which had previously held the burden of helping the needy, there emerged a growing crisis of social care. After some piecemeal efforts over the next century, the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601 created a system administered at parish level, paid for by levying local rates on rate payers. Relief for those too ill or old to work, the so-called ‘impotent poor’, was in the form of a payment or items of food (‘the parish loaf’) or clothing also known as outdoor relief. Some aged people might be accommodated in parish alms houses, though these were usually private charitable institutions. Bridgwater’s had Alms-houses outside the West Gate, and the South Gate. This system was a parish-based and a pauper applicant had to prove a settlement. If they could not they were removed to the parish that was nearest to their place of birth, or where they might prove some connection; some paupers were moved hundreds of miles.

The Workhouse Test Act of 1723 gave authority for the establishment of parochial workhouses, by both single parishes and as joint ventures between two or more parishes. The vast majority of people obliged to take up residence in workhouses were ill, elderly, or children whose labour proved largely unprofitable. The demands, needs and expectations of the poor also ensured that workhouses came to take on the character of general social policy institutions, combining the functions of creche, and night shelter, geriatric ward and orphanage. Bridgwater’s first proper workhouse was established outside of the South Gate.

During the Napoleonic Wars it became difficult to import cheap grain into Britain which resulted in the price of bread increasing.and many agricultural labourers were plunged into poverty, and some farmers were able to take advantage of the poor law system to shift some of their labour costs onto the tax payer.

The 1832 Royal Commission into the Operation of the Poor Laws New Law decreed the new Law must be governed by two overarching principles: *”less eligibility*”: that the pauper should have to enter a workhouse with conditions worse than that of the poorest free labourer outside of the workhouse and the *”workhouse test”*, that relief should only be available in the workhouse. The reformed workhouses were to be uninviting, so that anyone capable of coping outside them would choose not to be in one. Parishes should be grouped into unions in order to spread the cost of workhouses and a central authority should be established in order to enforce these measures. The Poor Law Commission set up by Earl Grey took a year to write its report, the recommendations passed easily through Parliament support by both main parties the Whigs and the Tories. The bill gained Royal Assent in 1834.

The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 created a Poor Law Commission, based in London, which in turn created local Assistant Commissioners: Somerset was organised by Robert Weale (whose area also covered Gloucestershire and Worcester-shire), who in turn the created seventeen Poor Law Unions in Somerset to replace the Elizabethan Poor Law, where it was administered on a parish basis. Each Union had elected Guardians, drawn from the gentry and better-off tradesmen.

The Poor Law Commissioners issued detailed instructions as to how the workhouse was to be run. The object was to make the able-bodied pauper worse-off than the worst paid labourer. Until 1842 all paupers took their meals in silence. There were no books or newspapers, and smoking was forbidden. Until 1842 paupers had no right to see their children. The able-bodied were kept active by stone-breaking for road repair, oakum-picking, and grinding corn by hand.

The Commissioners issued six sample dietaries, specifying the daily rations each pauper was to receive. Bridgwater’s Guardians adopted ‘No 3’:

Bridgwater Union was established in May 1836, and covered 40 parishes (with Bridgwater) and a population of 28,566. The existing poor houses at Lyng, Middlezoy, Over Stowey, Nether Stowey, Greinton and Stockland Bristol, were all closed, leaving Bridgwater parish poorhouse, outside the south Gate, with North Petherton as an auxilliary. While the new Union workhouse at Northgate was being built in 1836-7 the paupers from the Union were crammed into these two house. Bridgwater normally held around 75 inmates, but was held it could hold 112 – by making each bed hold more than one pauper, thus the resulting over-crowding, bad diet and sanitation caused outbreaks of dysentery and measles, which killed round 1/3 of the inmates.

Local protests at the inhumane treatment were led by local doctors and John Bowen, a Bridgwater wine merchant, and this led to a Lords Inquiry held in the summer of 1838, where 43 local people gave evidence over 19 days. Their printed testimony occupied over 800 pages.

A new workhouse was designed as a hexagon on the Panopticon principle, (from the Greek pan, all; opsis sight), where three wings, for men, women and children, radiated from the centre from which they might be observed at all times by the staff. The buildings bounding the hexagon were various workshops and stores, and the spaces in between were divided by high walls so the sexes should not mix. The hospital blocks to the left of the site were not added until later in the C19.

The Early Years

John Bowen described the first years of the workhouse in his pamphlet: The Union Work-House and Board of Guardians System, 1842, from which the following is condensed.

He began by commenting on the severe outbreak of dysentery in the Southgate poorhouse, due to overcrowding, while Northgate workhouse was built and went on to show that much sickness continued in the new building.

May, 1836.— The rate of wages in these 39 parishes, was 7s. a week, with cider or beer. The annual amount expended for the relief of the poor, before the formation of the union, was less than 16¼d. in the pound on the property-tax assessment, while in some other districts, where wages were 13s. a week, the poor-rates amounted to 6s. 8d. in the pound. Thus the labourers received about two-thirds the amount of wages, and one-fourth the amount of relief in poor-rates, which was paid in many other places. The hardness of the new law caused the board of Guardians to disallow the use of the pall and the usual tolling of the bell at funerals.

Before the formation of the union the inmates of the Bridgwater workhouse were aged, infirm, or children—there was seldom an able- bodied person in the house. When Bowen was overseer of the poor, he found in 1830 that the ages of the first thirty on the list averaged more than 74 years each; and that those thirty persons were more than 70 years of age, on the average, before they were taken into the workhouse. They were kindly treated, properly but frugally fed, and allowed a small quantity of table-beer daily.

August, 1836.—The little indulgences enjoyed by the aged poor in the workhouse, such as beer, tobacco and snuff were stopped, the house was closely packed with helpless persons from the surrounding parishes, and the commissioners’ dietary regulations were rigidly enforced.

September 27.— The visiting committee, noted“ The aged poor are afflicted with colic and diarrhœa, [Dysentery] and the children suffering from the same complaints.”

October 25.—Thirty-three cases of illness were reported, and the medical officer reported to the visiting committee that the dietary was producing disease among the inmates of the workhouse. He was told that the general dietary was no concern of his ; that he was to attend to the sick, and that only. The crowded state of the house meant that five or six diseased children were frequently put into the same bed, while of grown up persons, there were in some cases three in a bed, some of them labouring under diarrhoea, wallowing all night unchanged and unattended to in puddles of their own fæces.

This situation continued into 1837.

April 14, 1837.—Twelve cases of diarrhoea on the medical weekly return ; several of the wretched sufferers had been seized in the course of the week. Under these alarming circumstances the visiting committee requested the medical officer to attend them at the workhouse, when that gentleman again strongly urged the necessity of making an alteration in the diet. The visiting committee unanimously recommended the suggestions of the medical attendant to the board of guardians, calling their attention to the appalling fact, that 30 persons had died in the workhouse out of an average of 94 inmates.

April 21.—Twenty-two severe cases of diarrhoea in the house, many of them hopeless, and several lighter cases not included. The foetid stench throughout the whole house was so intolerable, after a lengthened discussion, which principally turned upon what the Poor Law Commissioners might possibly say or do, in case their dietary regulations were infringed, it was determined to act on the medical man’s recommendation. Thus six months after the surgeon had repeatedly called the attention of the board to the fact that the Commissioners’ dietary had produced a most distressing complication of diseases;—after this long and frightful period of torture and death, a reluctant permission was extorted to abate the deadly nuisance. At this time 30 persons had died in the house, and ten, who were then suffering under the disease, were carried off in the course of the year.

The Northgate workhouse became active towards the end of 1837.

A statistical table produced to the 1838 Enquiry noted the numbers of workhouse inmates until June 1838. This extract shows the last quarter for 1837,and is assumed to begin from when the Workhouse became active in mid November.

| Class | Week* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEN | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th | 13th |

| Able-bodied | ― | ― | ― | ― | 1 |

| Temporarily Disabled | 11 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| Old and infirm | 17 | 16 | 15 | 16 | 16 |

| YOUTHS | |||||

| Nine years to sixteen years | 23 | 23 | 24 | 24 | 22 |

| BOYS | |||||

| From two to nine | 31 | 32 | 34 | 33 | 34 |

| WOMEN | |||||

| Able-bodied | 8 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 13 |

| Temporarily Disabled | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Old and infirm | 20 | 20 | 20 | 21 | 21 |

| GIRLS | |||||

| Nine years to sixteen years | 20 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 18 |

| From two to nine | 28 | 29 | 28 | 28 | 27 |

| Infants | 8 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 10 |

| Totals | 170 | 172 | 174 | 173 | 178 |

More than a hundred (roughly 65%) of the inmates were under 16 years of age, and very early in 1838 the weekly totals increased to more than 200 and remained at that level.

November 23, 1837.—A poor man, in an advanced stage of typhus fever, was wilfully placed among the helpless old inmates of the workhouse, who had no opportunity of escaping beyond the reach of infection. A considerable number of them caught this formidable disease and died.

January 19, to March 2, 1838.—During these six weeks, in the depth of a most severe winter, more than 200 poor, mostly from the surrounding agricultural parishes, were subjected to “the workhouse test” when that house was ravaged by typhus and other pestilential diseases. In four weeks 12 persons, mostly children, were carried off by inflammation of the lungs and other diseases, ascribed “to the poisonous effluvia generated in close and over-crowded apartments which poison is known to act with intense virulence on children and others who have been accustomed to the open air.

June 12 to July 27.—Evidence was given before the select Committee of the Lords, but their Lordships declined to report, on the ground of there being “great difference of opinion in the Committee.”

In the coarse of the enquiry a considerable number of witnesses, including an ex officio guardian, four members of the visiting committee, and the medical attendants and governor of the workhouse, corroborated by the official records of the board, deposed to the principal facts charged ; while not an atom of contradictory matter was established. The whole evidence brought forward by the authorities resolved itself into “I do not know,” and, “I do not remember.”

August 3, 1838.—Report of the medical officer of the workhouse:— “I must beg to draw the attention of the board of guardians to the propriety of erecting an infirmary perfectly detached from the union-house in consequence of some conversation which passed between me and the physicians who have inspected the house, and who considered it not sufficiently ventilated for the well-doing of the sick, whilst it would be difficult to afford accommodation, if, on the approach of winter, many sick should be admitted, and any malignant disease should prevail among them.”

The Lords’ report was published on 15 August, 1838

October 18.—The medical officer again directed to the inconvenience which exists from the want of proper apartments for the sick labouring under different diseases. … From want of proper apartments for the sick, the fever-ward has been successively made the receptacle for a man labouring under congestion of the brain, which appears likely to terminate in typhus; then for women suffering from syphilis, and now is converted into a room for the smallpox. The eye-ward is now filled with children with eruption ; so that should ophthalmia again prevail in the house we are without a proper room

“The men’s sick ward is now as fall as it can be, with a prospect of their doing well; it is filled with a variety of cases, from syphilitic rheumatism and syphilitic eruption to simple debility. Should any malignant disease prevail among the men, we have not, that I am aware of, apartments in which they could be placed.

“I therefore beg again earnestly, yet respectfully, to urge upon the board the necessity of their most seriously considering the founding of an infirmary on a large scale, calculated to meet every exigency that may occur.”

October 19.—Minute-book of the board of guardians. Resolved, “That the report now read from Mr. Ward, in which he gives a statement of the general condition of the house, as regards the health of its inmates, and suggests the formation of an infirmary, … After a long detail, showing that more persons could be packed into the sick wards than they then held, the committee referred, as follows, to a previous resolution:—

“With regard to erecting an infirmary, the committee cannot recommend any additional outlay, as they are quite satisfied that the present buildings will afford accommodation for a greater number of patients than are likely to require medical relief within the union house, and the opinion of your committee may be better ascertained by the resolution of your committee, entered into at their meeting on Friday last, and which is hereunto annexed.”

They suggested that the building housing the Registry Office, created for the new Civil registrations of Births Marriages and Deaths, be appropriated

January 16, 1839.—The medical officers reported:

“That they had discovered 111 cases of disease, many of them of an infectious character, mingling with the clean inmates, without any order or arrangement for their separation.

“That 50 children slept in a room 27 feet by 15, and that they found other apartments bearing similar proportions to the number of occupants.

February 1.—Extract from the visiting committee’s report:—

The number of inmates on the sick list is 164!

At this period the frightful number of 117 deaths had been recorded in the workhouse obituary as a natural consequence of this compendious system of slow poisoning ; and under the pernicious operation of the “foetid air which the poor were obliged to breathe,”

January 4, 1842.— Fifty persons under the care of the medical attendant, and, notwithstanding all former ravages, the mortality in the workhouse within the last six months “greater than he has ever known it since his connexion with the establishment.”

January 11.—Medical Attendant’s Weekly Report.—Two deaths have taken place since my last report, and many cases of measles have appeared. Many of the inmates are suffering from severe colds and coughs, which, in my opinion, are partly produced by their going to church this cold weather without sufficient covering.—56 sick, 9 head diseases.

“January 18.—Medical Attendant’s Report.—There should be a comfortable ward provided for a few cases which are now in the large infirm ward. They are so offensive as to vitiate the air, and render it disagreeable to the other inmates.

“January 25.—Itch has appeared among the inmates. I have been obliged to put the itch cases in the vagrant ward for want of better accommodation. 71 on the sick list!

“February 8.—One case of smallpox has appeared since last week, and, for want of better accommodation, I have placed him in the men’s sick ward; which being full I have since been obliged to place other cases in the men’s small infirm ward.

“The inmates should not be allowed to go to church this severe weather without sufficient covering.”

February 22.—Proceedings at the Board of Guardians.— That it is expedient to adopt the advice of the medical officer, and forthwith build a detached hospital for the reception of the sick pauper inmates of the workhouse.”

“That the consideration of building an hospital be postponed to this day four months;”

February 24.— The diarrhoea has recommenced its ravages in the house ; 35 persons have been seized in the course of yesterday and to-day!

March 1.—Medical Attendant’s Report.—During the week so many cases of diarrhoea occurred, that the visiting committee were convened to consider, the cause of the sudden appearance of the disease, and to sanction any steps that might be deemed necessary to arrest the progress. Rice has been substituted for the usual diet, in these cases, and I should strongly recommend to the board, the propriety of giving up the boys’ school-room for the men, as the present day-room is much too small to accommodate, with safety to their health, generally from twelve to eighteen persons. One death has taken place from small-pox, and three other cases have appeared since my last report

March 8.—Small-pox it on the increase, and the accommodation afforded is not sufficient to allots of a complete separation—a strong proof of the necessity of a hospital.

Itch has again appeared among the inmates.

(Signed) Abraham King,

Medical Officer of the Workhouse.

Such is the condition of the unfortunate inmates of the Bridgwater union workhouse, after a protracted parliamentary enquiry, and a five years’ struggle with the system, and the contrivances of the Poor Law Commissioners !

“The great secret of Poor Law Reform,” says the Assistant Commissioner Tuffnell, “and the main object of all the machinery of guardians, workhouses, relieving officers, &c. is to place the pauper in a worse condition than the independent labourer.” Thus “the main object” of all this complicated machinery is not to relieve the poor, but to punish them ;—not to administer to their necessities, but to deter them from applying for relief.

―――

A little-known fact to arise is the high proportion of children and young people held there. This raises questions abut their origins and what became of them – perhaps emigration.

Little is known about the management of the workhouse during the C19 and into the C20. It was not mentioned at all in the histories of Bridgwater by Jarman and Powell, and only very briefly by Squibbs, and only touched upon by the VCH Somerset.

The census records will show who was there every 20 years. The 1841 Census, for example, showed there were 197 inmates and six staff, Master, Matron, school master and mistress and porter. That for 1881 recorded a total 242 inmates, of whom 5 were staff.

Later in the C19 the Bridgwater Mercury regularly reported in detail the deliberations of the Board of Guardians, where paupers made their case for help, – and noted what they achieved.

The original part of the workhouse and the lodge were demolished in the late 1970s and redeveloped into the Enterprise Centre. Plans for the Enterprise Centre date to May 1976, which is presumably about the time the workhouse was pulled down. The Enterprise Centre was in turn demolished in the 2010s to make way for a supermarket. The Blake Hospital thereafter became a geriatric hospital within the NHS and survived into the 21st century as a social services department of Somerset County Council. This was demolished in 2016 and replaced by a school. Northgate school (opened in 2017) has the same footprint as the workhouse hospital block.

A survey of the Workhouse’s boundary wall, the only feature surviving, can be found here.

TW