Colin Symons Cooper (1927-2012) was a grandson of Clifford James Symons (1857-1943), partner in the brickmaking firm of Colthurst, Symons and Co., which owned yards at Bridgwater. His father Frederick Arthur (Tom) Cooper was Joint Managing Director of the firm. Frederick was born in Birkenhead and moved to Bridgwater with his family, remaining until 1940, when they moved away.

He wrote the following account of his childhood and the town in 2009. We have the kind permission of his sons, Ben Cooper and Dan Cooper to publish it here. The Museum mounted an extensive exhibition about the Bridgwater-made Ketch Irene, in 2010, which prompted him to make contact with me. In his own words:

I have attached 5,000 words about clay, Colthurst Symons, and Bridgwater generally. I add to it (and edit it) every time I open the file, but I have to send you something soon, so here goes. It’s based on personal memory. I have no written records or documents, so I’m open to informed correction – though not to opinion based on ignorance and prejudice. Please tell anyone who wants to argue about the pronunciation of ‘Irene’ that I may be 83 but I am not senile yet, and my memory is clear on that point. I can only doubt the opinion that Irene was named after a Miss Irene Symons; she may have been a member of the other side, the family of Oswald Symons, a cousin (I think) of CJS, though it’s unlikely. I don’t think Oswald had a stake in Irene. Did my grandfather perhaps have a daughter named Irene, dead in infancy or still born? I think not: my mother would have told me. I remain in the dark, until one of your researchers can shed some light.

[In relation to the exhibition,] I was intrigued by the clip from Peter Grimes. I met Britten when he came to the Arts Centre (1950? 1951?). He and Peter Pears had performed at the Arts Centre, and were staying in the large Wembdon house of Gwen Pollard, whom I knew very well and liked: a formidable ‘mover’, a woman who made things happen, yet whom I found always pleasant and friendly. She had a formidable mezzo voice, and my mother from time to time accompanied her at the piano.

Please note that the paragraph indicated with ** contains sensitive subject matter, which some find upsetting.

Colin Cooper 1927-2012

Colin’s family lived at Crossways House, Somerset Bridge, and he lived there between 1928-1940. As a boy he was an amateur violinist, and he developed into a man of many talents, working as a playwright, music critic and author, active as a scriptwriter for Television and Radio, who also wrote at least one crime novel under the name Daniel Benson. His first science fiction work was a six-part BBC radio serial, “Host Planet Earth” (1966) and his novels include The Thunder and Lightning Man (1968 – the inspiration for this was Andrew Crosse (1784-1855) of Fyne Court, Broomfield, Somerset,the early pioneer and experimenter in the use of electricity), Outcrop (1969) and Dargason (1977). Cooper returned to science fiction in the year of his death with The Princess from Planet Alpha (2012).

He began teaching himself guitar in 1962 as a break from long hours at the typewriter, and later took lessons with Dave Alcock and George Clinton. He eventually began teaching guitar himself, both privately and at the London Education Authority’s Adult Education. Through his career he co-founded both Guitar magazine and Classical Guitar and regularly contributed to Gendai Guitar. He once wrote, “It might be fair to say that I am a writer who was seduced by the power of music and became its servant rather than its master.” At the age of 82, Colin wrote his first book about music, Did They Like Me?.

Colin died at Hastings on 25 August 2012.

Biographical material compiled from the online Encyclopaedia of Science Fiction and The Blog of Classical Guitar of America. Also see his Guardian Obituary, and his Guitar Blog.

Tony Woolrich 10/03/2025

Clay Recollections

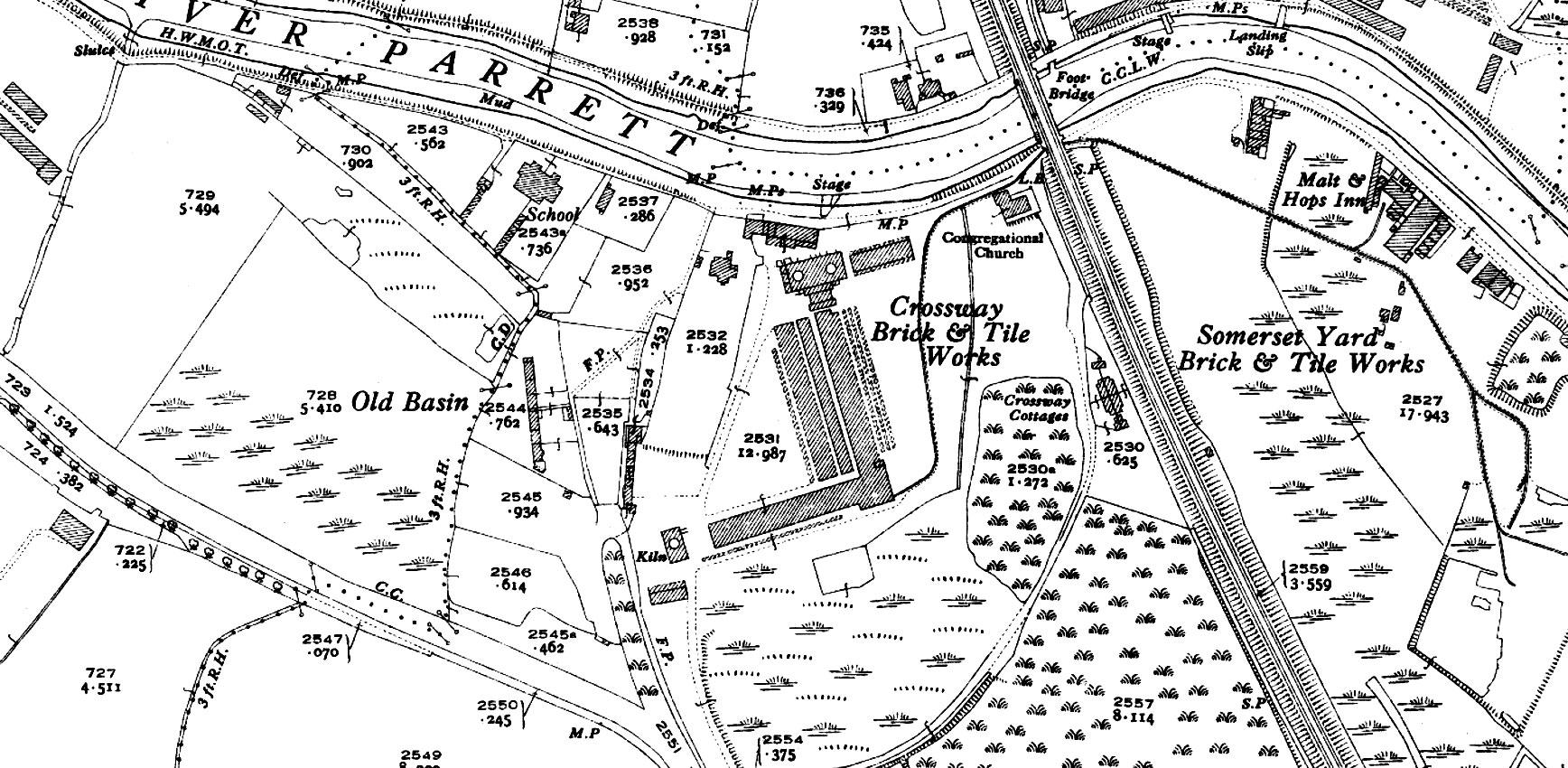

THE media generally are ignorant of the South West’s industrial history, preferring to think of towns like Bridgwater, if they think of them at all, as sleepy meeting places for weekly cattle markets. Bridgwater is, or was, a market town; it was also a centre for the thriving brick and tile industry for more than 200 years. Much of the Somerset plain is rich in alluvial deposits which afford a generous amount of good quality clay suitable for firing and subsequent use as a building and, particularly, roofing material. This trade came to an end in the 1960s, unable to compete with much cheaper (though not so long-lasting) concrete tiles.

During the 1890s there was much unrest among the workers. Trade unionism was in the air, and the brick and tile makers became acutely aware of their sometimes desperate situation. Because frozen clay is impossible to dig in the winter, roughly half the workforce was laid off. This meant that, since about half of Bridgwater’s male population was employed in the industry, a quarter of the men in Bridgwater were out of work for a large part of every year. With small pay packets and no savings or unemployment benefit to fall back on, the only alternative to starvation was the workhouse, where they were at least kept alive. When my mother paid a visit to the Bridgwater, she came back distressed at the lack of common humanity. She was satisfied that the occupants were in no danger of starvation, but she felt that married couples should not be separated. This was either just before World War II or just after. Now, of course, even convicted criminals can received ‘conjugal visits’.

Another restriction, and one that could have been more easily remedied, was that couples separated by the institutional rules (or in many cases by death) were not even allowed to keep a photograph of their nearest and dearest at their bedside. The rules were drawn up before family photographs became common, and no one had thought of revising them.

After a number of unsuccessful strikes, matters came to a head with the riots of 1896, in which 30 workers were brought before the magistrates and the Riot Act was read in public. At the time I lived there (1928-1940), the situation had stabilised to a great extent. Whatever their private grievances, the workers played their part in a profitable industry, even if all the profit went to the shareholders.

One of the seven yards owned by Colthurst Symons was at Somerset Bridge, where I grew up. It was an area of clay pits, desolate ponds and tall rushes in which the only industry was the brickyard, and the only dwellings were those occupied by the men who worked in it.

On the town side of the River Parrett there was a farm where you could buy ten apples – Morgan Sweets – for a penny. It was less than 200 yards away as the crow flies, but I had to walk a quarter of a mile to the railway bridge in order to cross by the wooden walkway, and the same distance on the opposite bank. It was worth it to a hungry schoolboy.

On our side of the river, road access was available only by a wooden swing bridge over the Bridgwater-Taunton canal, which you reached via the Huntspill turning on the Taunton Road. The bridge was narrow, and rumbled ominously when a car was driven across it. When World War Two began in 1939, the white-painted rails were removed, presumably to impede, in some mysterious way, the advance of the Panzer tanks that were continually expected but which never arrived. It did, however, make a car crossing more hazardous, especially at night, in the black-out, with masked headlights that only shone a thin, flat beam at best. As the car went up the incline to the bridge, it illuminated only the air above, and one of us children had to get out and guide my father across.

The only other access to the area was along the river bank from the Taunton Road bridge a mile downstream, or by a similar path from the other direction. The Taunton Road bridge was a solid enough structure, built to carry a horse and cart or a lorry to a depot where stacks of tiles, wheeled on barrows from the manufacturing yard half a mile away, awaited transfer to the docks or the railway station. After that it was by footpath only, to the various dwellings scattered along the bank, including ours, and to the Elementary school not far from our house.

In 1938 the journalist Vernon Bartlett fought a by-election in Bridgwater, and a meeting was held in the school. Bartlett arrived by car outside our house and was escorted by my father from one gate to another through our back garden, a short cut, I holding a torch to show them the way along the narrow path. I wasn’t invited to the election address, but I knew that Vernon Bartlett had been to Germany and had seen Hitler’s rearmament for himself. He easily disposed of his Conservative opponent, one of the Heathcoat-Amory family, who had stoutly maintained that Hitler was bluffing and that his tanks were made of plywood. No one believed him, and Bartlett was elected as an Independent Liberal – I think the first time the Tory grip on Bridgwater had been loosened.

The railway bridge carried the Great Western Railway’s main line to Devon and Cornwall. This was a huge fascination, and we three children used to climb the high wooden hoarding that was supposed to prevent us from straying on to the railway. It was forbidden, but we only wanted to look in awe and wonder at the huge locomotives as they picked up speed after leaving Bridgwater station. Dragon-green monsters, hissing steam and thunderous sounds, they were of the Hall and Castle class; there may have been others used by GWR to pull their passenger trains, but I had no eyes for them. The Halls were coupled 4-6-0, and were made at Swindon until 1943. In the Harry Potter stories, the fictitious Olton Hall pulls the Hogwarts Express. The Castles were also coupled 4-6-0, and produced until 1950. It was the Tregenna Castle that in 1932 pulled the Cheltenham Flyer from Swindon to Paddington at an average speed of 81.68 mph, a world record for steam traction.

When we were tired of the steam trains, we watched Colthurst Symons’s own train carry clay to Crossway Yard from the pits on the other side of the railway line. This narrow-gauge single track carried a number of small tipper trucks drawn by a little Lister diesel locomotive, and was interesting chiefly because we could get closer to it than to the GWR giants. Besides, the driver didn’t shake his fist at us, as the GWR drivers sometimes did. Colthurst Symons bought four of these little locomotives during 1935 and 1936, so the one at Crossway Yard must have been new when I first saw it. Other purchasers of Lister diesel engines included, curiously, HM Borstal, who bought two, and the National Rifle Association, Bisley. What could they have used them for?

Crossway House was detached and had four bedrooms. It stood in about two acres adjoining the brickyard. To get to it, a car had to go through a considerable part of the brickyard itself. There were three entrances to the house: a curving driveway of about a hundred yards up to the front of the house, a small gate at the far end of the brickyard, and a small wooden gate that opened on to the river bank. The house adjoined the brick and tile works, and was owned by Colthurst Symons. Clay was a prominent constituent of the garden, but it did not seem to impede the growth of the vegetables and fruit.

**My father had a car, a two-seater Austin with a dickey seat at the back, which pulled open to reveal two seats, in which we three children could squeeze, unprotected from the elements. Later he acquired a Hillman Wizard with the same seating arrangements: it had the distinction of appearing in a national newspaper’s list of the 100 Worst Cars ever built. But that was much later; its faults and breakdowns were seen to by the firm’s service engineer, Mr Shapter. The car was necessary for my father’s work, which involved travelling around the yards. All this, of course, gave the impression to our neighbours that we were well off. So we were, in comparison to them. We even managed a servant, who came in to help with the housework. She was usually a young woman who been removed from service in Octavian House because my grandmother suspected my grandfather of misbehaviour. Whatever the truth behind it, there was a procession of these unfortunate girls willing to help my mother until such time as more substantial work could be obtained. The one I remember best was Winnie, a lively and pretty girl of about 18. Whatever my grandfather did or did not do in his late seventies, I certainly loved her in my pre-adolescent way. It was Winnie who talked to me on the long summer evenings when she was baby-sitting, who stimulated my interest in science fiction and who lent me copies of the works of H.G. Wells. My father’s reading shelves were filled with numerous novels by Sidney Horler featuring a gentleman criminal called Blackshirt, which I read uncritically. Apsley-Gerrard’s The Worst Journey in the World, the story of Scott’s last polar expedition, was also there, and I read that too. The Collected Works of Charles Dickens were in faded red cloth covers, and made a forbidding row. I wanted more, and Winnie gave it to me.

There was no electricity at Somerset Bridge in those days. Our lighting was by paraffin lamps, our cooking carried out on an Ideal coal-fired kitchen range. My father had a coal allowance from the company. It was of low industrial quality, and not ideal for burning a family’s living room. But it came with the job, and was welcome. The brick and tile works was powered by a horizontal steam engine, another source of fascination; I used to stand at the end and watch the powerful piston thundering towards me, retreating at the last moment but not before I had time to question the wisdom of staying so close to a lethal beast when my instinct told me to turn and run.

Because my father had married a daughter of C.J. Symons, he had been given a job in the East Quay office by my maternal grandfather. For these reasons, my presence in the brickyard was tolerated. It never occurred to me that I might be a hindrance in the existence of these hard-working and underpaid men, but their cheerful friendliness was not the least of the many pleasures my visits gave me.

Colthurst Symons had a brick-making machine at Somerset Bridge. Powered by the horizontal steam engine, it helped to meet local demand, but it could not compete in price with the products of larger companies such as The London Brick Company.

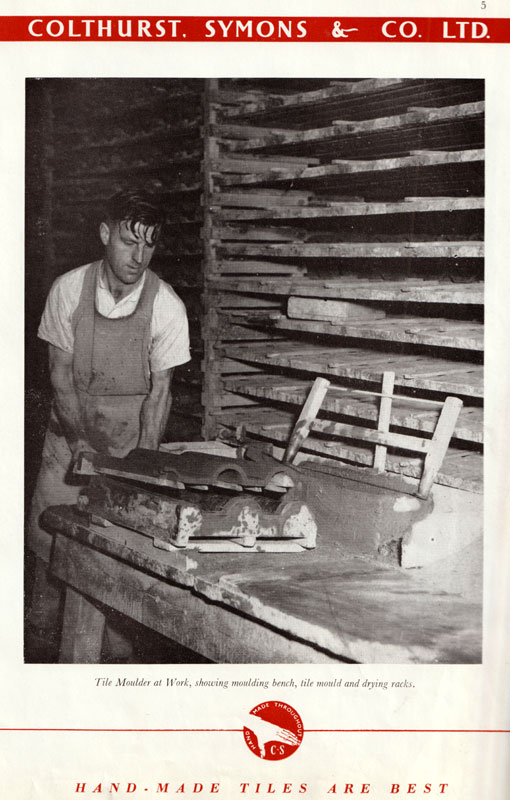

The tilemakers worked in long, low sheds, well heated (to facilitate the drying process before kiln firing) and permeated with the characteristic smell of freshly processed clay. A slab of clay would be slapped on the mould, pressed down to fill every space, and the excess sliced off with a cutter of thin wire tautly stretched on a wooden frame similar in appearance to that of a bow saw. Then the tile would be slipped out of its mould and left to dry on the long racks until it was ready to take to the kiln. A quick dusting of fine sand, and the mould would be ready for the next tile. There was said to be a mystery regarding the making of tiles. Perhaps there is. At each of Colthurst Symons’s yards, the clay was different; moulds had to be made accordingly to allow for the difference in shrinkage. As my father once put it, ‘Each clay face holds its own mystery’.

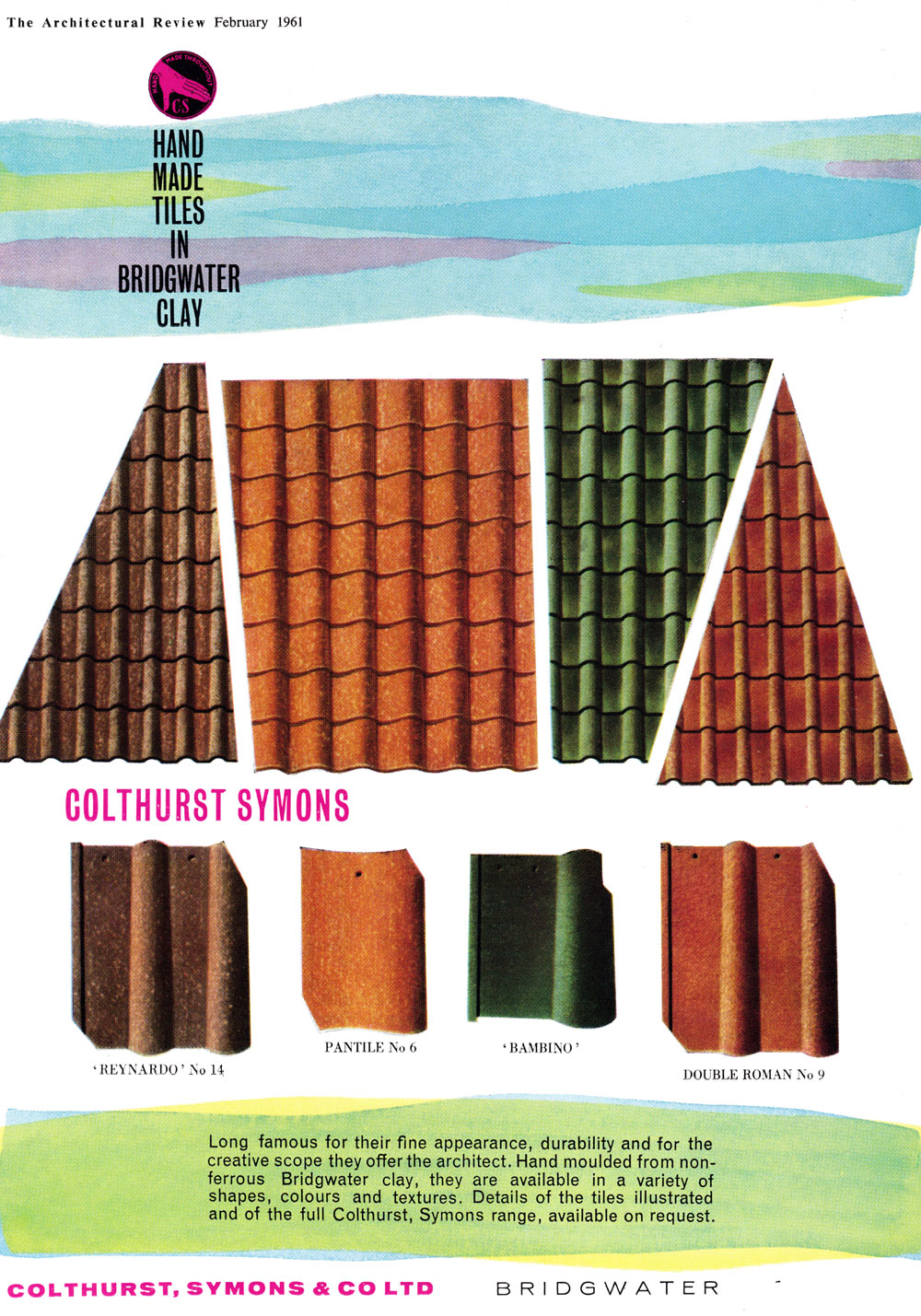

Glazing was a separate craft. Colthurst Symons had their own secret recipe, as had all the other tilemakers, and it produced a colourful range of roofing tiles, of which Apple Green seemed to be the most popular. Half the houses and just about all the hotels along the south coast seemed to have this shimmering green display above white pebble-dashed walls. A deep Mediterranean blue was another big seller. Roman pantiles, interlocking Double Romans, the smaller Bambino, are some of the types I remember.

I watched as the tiles were taken to the kiln for firing. A succession of workers trundled their wheelbarrows up and down two planks. When the kiln was full – over 5,000 tiles – the planks were removed and the entrance sealed up with bricks and clay. As far as I remember there were no temperature gauges: it was all done by the skill and knowledge born of long experience and handed down to generations of apprentices.

Glazed tiles were washed in long, low tanks of water, alive with small flies skating along the surface. Underneath them paddled the insects known as water boatmen. Sometimes they would encounter my toy submarine which, when fully wound up, would actually dive for a few seconds.

Bricks and tiles were taken to the town by horse and cart (I was given a ride on a carthorse once), sometimes by a steam traction engine, and, later, by a more modern lorry, which was not so exciting. Sometimes the tiles would be taken to Bridgwater by barge. When the tide had begun to ebb and was at exactly the right level, a gate opening on the river, normally sealed up, would be opened and the bricks and tiles would be loaded into a barge, which would drift down to Bridgwater, to be unloaded on West Quay, between the Library and the Town Bridge. It was guided by one or two men with long poles.

My grandfather, Clifford James Symons, was the Managing Director. His surviving son, Hubert Arthur, always known as Jack or the Young Governor, was taken into the firm, but the disease of alcoholism was already taking a grip, and eventually he left, with a pension that enabled him to fuel his craving. He died at 58 or 59. I remember him as a good and generous uncle, an accomplished pianist, and great fun to be with when he was sober. My father, Frederick Arthur (Tom) Cooper, got to know the business well, and eventually became joint Managing Director, the other MD being Harold Foster, who had been the Company Secretary for many years and who knew the financial structure intimately.

Of the seven yards owned by Colthurst Symons, I remember five of them – six if you count Home Yard in Taunton Road, where there was a forge and where vehicles were serviced. The other five were Castle Field, Burnham, Somerset Bridge (Crossway), Puriton and Combwich.

A popular drink of the workmen was cold tea. They would bring a blue enamel flask of it, and it would last them all day. For a snack, they brought bacon, and the delicious smell permeated the low brick building where they ate and drank. When they weren’t there, numerous crickets chirped, attracted by the warmth (coal, used for heating the kilns, was cheap) and plentiful fragments of food. The men wore shirts without collars, peaked caps, waistcoats (usually unbuttoned) and trousers tied below the knee to keep them out of the clay and the mud. The boots were substantial, and needed to be. For handling the bricks and tiles, they were given thin rubber pads, red in colour, with a slot in the base for the hand to go through. Sanitation was primitive, a 2-seat wooden shack erected over a trench. There was little privacy, and no hand-washing facility that I could see, beyond the general water supply for manufacturing purposes.

The foreman, Fred Duddridge, worked in a small cabin alongside the main track – unmetalled, it could scarcely be called a road – with a desk but no telephone. Fred used to come into our house to use our telephone (Bridgwater 401), which hung on the wall in the lobby which led into my father’s own office. Fred treated the telephone with suspicion. It was still a comparative rarity in pre-war Bridgwater, and he felt it necessary to position his mouth a foot and half from the receiver and raise his voice several decibels. He was a sturdy, good-natured man, experienced in all aspects of the manufacturing process, and I would think a good foreman. A group photograph of the firm’s annual outing in 1927 is displayed in the Brick and Tile Museum. Fred’s father is also there, and so are his brother and his son.

I went with my family on the firm’s outing to Weymouth in 1937. We left early in the morning on the Somerset and Dorset line, from the station on the Bristol Road. The S & D was known as the Slow and Dirty line, or the Swift and Delightful, according to your experience. As a boy of 11, I found it delightful, though not at all swift, slow and delightful, in fact. The fleet was in Weymouth, and we took a boat trip around some of the warships, including the aircraft carrier HMS Courageous, sunk a few years later in the Second World War. The Royal Family came that day to review the fleet, and drove through the town in an open car, King George, Queen Mary and the two princesses, all waving in that slow, royal way that seems to be as well established as the throne itself. On the journey home there was no perceptible drunkenness, but a lot of joviality.

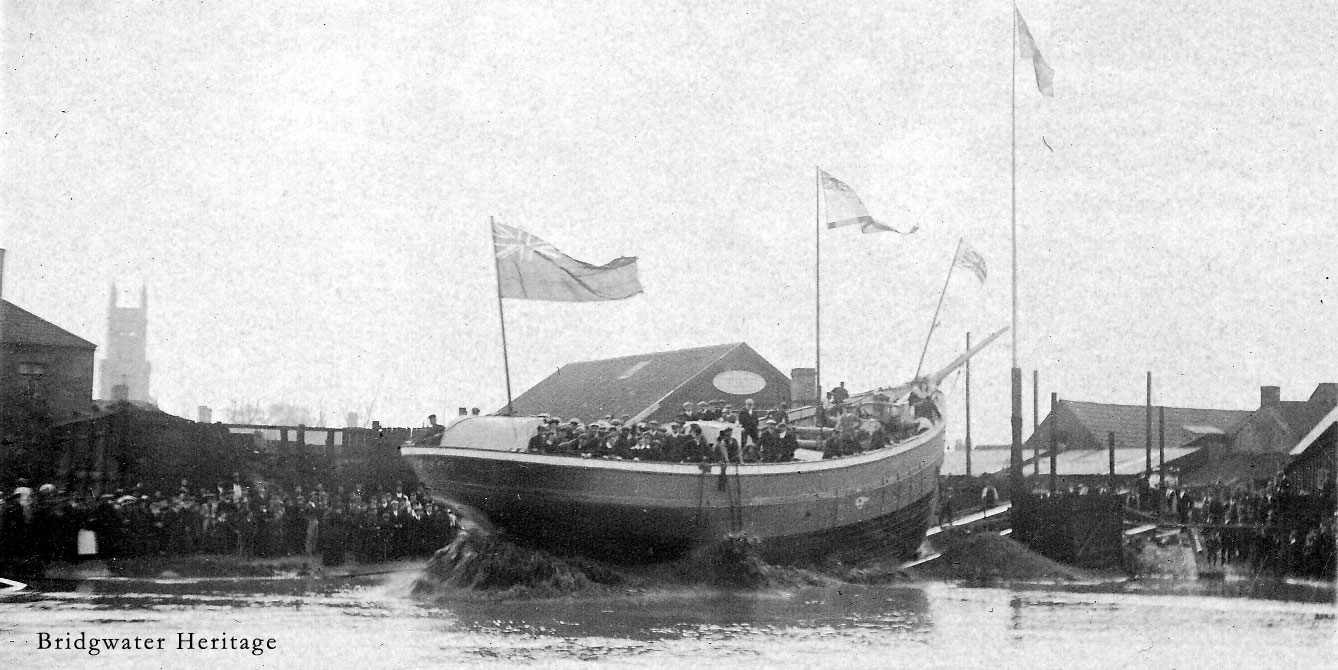

I was obsessed with the small sailing vessels whose home port was Bridgwater and which were used to carry bricks and tiles up the Bristol Channel and across to Ireland. At the time I lived near Bridgwater, Colthurst Symons owned three ketches.

As a boy, I used to cycle down to the docks and watch them being loaded, half hoping I would be invited on board to serve as a cabin boy on the long voyage to romantic Dublin. It never happened, of course, and it was not until 1980 that circumstances permitted a short voyage, measured in yards rather than miles, up the River Parrett. By that time Bridgwater’s brick and tile industry had come to an end, and Colthurst Symons had gone out of business. One vessel is mentioned in the novel Ulysses by James Joyce, where Leopold Bloom sees ‘the three-masted schooner Rosevean from Bridgwater with bricks’. Colthurst Symons owned Rosevean at one time, but by the time of the novel – based on a single day in 1904 and published in 1922 – she had been sold on. She ended her days on the banks of the Parrett.

The biggest, fastest and most elegant of the ketches was the Sunshine, which had the reputation of being the fastest sailer in the Bristol Channel. She had a figurehead, a generously busted female painted in vivid colours. Sunshine’s life ended sadly after a brief spell of excitement; after leaving the possession of Colthurst Symons, she was arrested for gun-running in the Mediterranean, taken to Genoa and broken up in 1953.

The smallest was the Fanny Jane, a cheerful little ketch whose black appearance, even her sails were black, as I remember, belied her nature. She ended her career as a grain tender, dismasted, in Bristol Docks.

The ketch that achieved international fame was the Irene, which those who loaded her, like those who sailed her, called the ‘Eye-reeny’, giving her the three syllables that were her due as a Byzantine saint. The later ‘Eye-reen’ was derived from the American folk-song first recorded by Huddy Ledbetter in 1932 and which reached the British charts in the 1950s, subsequently being adopted as anthem by Bristol Rovers.

‘Goodnight, Irene, Irene goodnight, / I’ll see you in my dreams.’

Well, I dreamt of her sometimes, but it wasn’t until Dr Leslie Morrish rescued her from dereliction and gave her a new lease of life, and a new profession, that she returned to my consciousness. Irene had been built in Carver’s Yard on East Quay, and was bought by Colthurst Symons before completion. She was launched in 1907, and christened by my Aunt Gladys, eldest daughter of C.J. Symons. On board were various other members of the family, including my mother, then a teenager of 17. (NB. This recollection, like most of the others, can be amplified by reference to documents in the Blake Museum.)

Leslie Morrish found her, derelict, on the Hamble river. After restoring her, he sailed her down the Thames and round the south coast to Combwich, the port from which she had sailed and to which she had returned so many times in the early part of the 20th century. The event was well publicised, and when I went with my family to spend a week in my brother’s caravan at Blue Anchor, I knew that her arrival was imminent. I had not expected, however, to see her one afternoon while we were exploring Bossington Beach. When I spotted a sail coming round the headland west of Porlock, I had no doubt that it was Irene, though it was more than 40 years since I had seen her afloat. I persuaded my family to leave their quest for unusual striped pebbles (flint streaked with limestone) and to get into the car.

There was no sign of Irene at Minehead. Watchet was the next possibility – almost a certainty, in fact, because it was getting late. But there was no sign in Watchet either, although we waited until past the time when she should have appeared. I heard afterwards that it been the skipper’s intention to put in at Watchet, but a combination of engine trouble and an offshore wind had made it impossible.

The next port was Combwich, and there we found Irene the next morning, stuck fast in the mud. The skipper had brought her in without a pilot, in the dark and with no knowledge of the Parrett estuary, and on a higher tide than usual, where the water, overlapping shallow banks, gave a misleading impression of the depth. It was a compelling sight, and I lost no time in clambering up the ladder with my two boys and introducing myself to Dr Leslie Morrish. ‘Never mind about that,’ he interrupted impatiently, ‘Get aft and jump up and down with the others’. I should have realised that he was a man under pressure, and left the formalities until later.

We joined a multitude of local people in jumping up and down in an attempt to free Irene from her embrace of Parrett mud. It produced no effect, despite a near-high tide, and eventually the freighter Bowness, on her way out of Cardiff, made a 12-mile detour to tow Irene off the mud. We were rewarded for our efforts with a short voyage up the Parrett before Dr Morrish turned her round and returned to Combwich. The entrance to the harbour is a narrow one, and it was probably a mistake to attempt it under Irene’s own power. There was a splintering of wood as the bows hit the wharf. ‘It’s only wood,’ announced the skipper cheerfully. One of the old brickyard workers standing near me on the deck said: ‘Thic zilly bugger, ur zhould’ve chucked a hrope across, like we used to do’. I’m sure he was right, but he had local knowledge and experience; the skipper hadn’t.

Among the most memorable men I met in those years immediately preceding World War II was Tom Bale. He was the firm’s potter, responsible for the chimney pots and other cylindrical goods, mainly garden pots that, although essentially a sideline, formed an attractive part of the Colthurst Symons catalogue.

Tom and his wheel were installed at Castle Field Yard, across the river from where the museum is now. His great passion was music, and he was a skilled and sensitive violinist. On the rare occasions when my father took me with him on his rounds, Tom would talk to me about the ten violin concertos written by Charles-Auguste de Bériot. Although I was learning to play the violin at the time, the name meant nothing to me, and it was only later that I heard some of his work. But by that time his music had gone out of fashion, and was very seldom performed. Tom Bale went on to become a leading light in Bridgwater’s musical activities. After the war I joined the Bridgwater String Orchestra, of which he was the leader, and got to know him better. A gentle man, he was nevertheless angry with my grandfather for refusing to pay him beyond the basic rate for the job, despite the fact that Tom was required to train apprentices in the craft.

Walter Palmer was a wiry youth of about 16 when my mother somehow arranged it so that he would come into our house, which adjoined Crossway Yard, and light our coal fires on cold winter mornings. For that he received a modest supplement to his meagre pay as a beginner in the brick and tile trade. I never met him after we left Crossway House, but I heard later that he had distinguished himself in the war by being decorated for bravery. Among the others, I remember Rosier, Spraggs and Keirle.

Other men in the company I came to know included Tommy Coleman, the carpenter, and Shapter, a skilled mechanic. Whenever my father couldn’t get his car to start (a fairly frequent occurrence) he would send for Shapter.

Based in Taunton Road, more or less opposite no.10 (Octavian), was Home Yard, which had a blacksmith’s forge. It exercised a magnetic appeal for me whenever I stayed at my grandparents’ house. At one time I thought I would like to become a blacksmith.

The Government buildings in Canberra, Australia, were roofed with glazed Colthurst Symons tiles. They were descendants of the fired roof tiles found in Greece in the 4th millennium BC, and for all I know they are still there: scarcely the peak of modernity, but beautiful just the same. The Company was informed that two out of a shipment of thousands arrived broken, but whether the contractor was expressing wonderment or asking for urgent replacements, I never knew.

There is no doubt that the brickyard workers were underpaid. Unsuccessful strikes in 1886, 1890 and 1893 achieved nothing, apart from a hardening of attitudes on both sides and several weeks without pay. The workers were driven back by sheer hunger. There was rioting in 1896, and my mother, then aged 6, remembered the family barricading themselves into Octavian House, 10 Taunton Road, where they lived. The Riot Act was read from the steps of the Town Hall, and more than 30 workers were brought before the magistrates. The cause of the unrest was obvious. The management maintained that low wages were essential for the survival of the industry; the workers argued that a decent living income was essential for efficient working and health of their families.

Life was hard in the brickyards. At one time, half the male population of the town was employed in the industry. During the winter, the ground would be too hard to dig, and about half the workforce – about a quarter of the town’s male population – would be laid off. The work being so seasonal, winter unemployment levels were high, hence the need to establish the workhouse at Northgate. My mother was appalled by what she saw on her visits. Well into the 20th century, married couples were separated and not even allowed to keep a photograph of their respective spouses by their bedside. But no one starved there, and that necessity appears to have occupied the authorities to the exclusion of everything else.

William Symons can take the credit for the popular Double Roman roof tiles. The kilns for firing them could take up to 5,000 at a time, and the temperature had to be just right if the tiles were not to crack in the firing process. The kilns would be loaded with faggots of wood and about 10 tons of coal. At the end of four days, the kilns would be sealed to extinguish the fire and left for another four days to cool. These products ended up all over the world.

Colthurst Symons ended trading in 1970, unable to face the competition from Marley’s concrete tiles, which were twice as heavy, usually lasted less than half the life of a hand-made clay tile, and were half the price. Sometimes they had to be replaced after only 25 years (though this is hearsay). I can vouch for the fact that the Bridgwater tiles on my Edwardian London house were still keeping the rain out in 1991, 85 years after they had roofed the new house in 1906.

While concrete tiles were largely responsible for the declining demand for handmade clay roofing tiles, Colthurst Symons had another problem. Business was excellent during the post-war building boom, and the shareholders came to take their annual dividends for granted. They did not hesitate to put pressure on the directors, a majority of whom were relatives, either by blood or by marriage. As a result, not enough was spent on market research and the development of new ideas for the future. It was assumed that a trade which had lasted for over 200 years in Bridgwater would continue without question. That assumption was mistaken.

I cannot be the only person who regrets the passing of the clay trade. Many new industries have come to Bridgwater. A town of fewer than 25,000 people has swollen to 36,500, and it is prosperous. But a lot of its old character has vanished in the process, and it has become almost indistinguishable from a hundred, perhaps a thousand, other towns in England. That, I am sometimes told, is progress. For me, the most exciting time in the town’s history came in the few years after World War II, when the two Georgian houses in Castle Street that had boasted a sizable theatre seating about 400 (I made my musical debut there c.1938, when it housed the drama and music school of Miss Jeffcoat) was taken over and totally supported by the Arts Council, their first in Britain. For several years it formed the artistic hub of Bridgwater, hosting events that could not have been afforded without outside support. The Arts Council eventually relinquished its control and the town itself took over the administration, as the Arts Council had always intended. The Arts Centre is now more of a people’s palace, where high art is mixed with popular entertainment, and as such is less in the national eye, as it was in the mid-1940s when it was thought that intense wartime interest in the arts could be extended into peacetime. So it did, for a time.

Two of the most encouraging aspects of contemporary Bridgwater life seem to me to be the Brick and Tile Museum and the Blake Museum, the first a fascinating evocation of a vanished trade, the second a long-established institution given a new vitality by the commitment and the sheer hard work of the volunteers who are patiently amassing such a wealth of information about Bridgwater’s past. I am sure I am not the only exile who is going to keep in touch through the internet.

© 2009 Colin Cooper

reproduced with the kind permission of his sons, Ben Cooper and Dan Cooper

webpage March 2025