Dr Morgan’s School for boys has a special place in Bridgwater’s history. Generations of boys were educated there. But it nearly disappeared during the 19th century.

Dr Morgan and the Gift of Education

Dr John Morgan, a physician, practiced in Bridgwater when gentlemen wore powdered wigs and the Battle of Sedgemoor was still in living memory. He was a member of the Common Council, now the town council, and was Mayor in 1720.[1] He would have been aware that charitable schools had been established in many towns in England and seen a need around him.[2] Dr Morgan died in 1723 and in his will, he directed that the income from his estate at Hoccombe, Lydeard St Lawrence, be used to ‘teach and instruct the sons of the decayed inhabitants of the borough and parish of Bridgwater.’ Thus the sons of respected but poor townsfolk could receive an education which would otherwise have been unaffordable. [3]

The earliest known master of Dr Morgan’s is Richard J. R. Jenkins (1763-1823) who was born in Tenby, Wales, the son of an excise officer. He studied at Oxford University and was ordained as a deacon in 1786. He married Catherine Crandon at St Mary’s parish church in 1788, so he had some connection with Bridgwater prior to being appointed master of Dr Morgan’s in 1789. The school was on the 1st floor of the Church House in High Street. The boys, in their uniform blue coats and blue caps, climbed a staircase from Mansion House Lane to reach the schoolroom.[4] Richard focused on teaching reading, writing, arithmetic and religious education.

By law, all schoolmasters had to conform to the Church of England faith and the grammar schools preferred schoolmasters to be clergymen with a degree. In the space of three exciting weeks in September and October 1790, Richard was ordained a priest and the Bishop licenced him to be a preacher and reader in Bridgwater. At the same time the new Rev. Jenkins was also appointed master of the King James Grammar School. As the two schools now had the same sole teacher, both may have used the schoolroom in the Church House, at different times. Richard was awarded a B. & D.D. from Oxford in 1808 and resigned from both schools in 1809 to become a curate in Kent.[5]

The Borough sold the Mansion House in 1801 and whether the school moved or remained in the Church House paying rent to the new owner is unknown.

The new Dr Morgan’s schoolmaster appointed in 1809 was Thomas Gill (1779-1845), who was born at Tiverton, Devon. He was a writing-master in Bridgwater in 1803.[6] Mr Gill’s writing school had opened by 1804.[7] Thomas left Dr Morgan’s school after only a year. He was neither a graduate nor a clergyman, but he was a successful teacher. In 1817 Thomas was the master of a private boys’ school in Castle Street at which he taught penmanship and mathematics. He had a ‘boarding academy’ at Cornhill in 1820, a school in Castle Street again in 1830 and a day school for boys in High Street in 1839. He was also a part-time bank actuary. He died ‘of a lingering illness’ aged 66 in July 1845, a schoolmaster who was “highly respected by all who knew him.” There is a plaque in his honour in St Mary’s Church, Bridgwater. [8]

TO THE MEMORY OF THOMAS GILL UPWARDS OF FORTY YEARS A DILIGENT INSTRUCTOR

OF YOUTH AND DURING TWENTY-SIX YEARS THE INTELLIGENT AND UPRIGHT

ACTUARY OF THE SAVINGS BANK IN BRIDGWATER

THE AFFECTIONATE PUPILS HAVE ERECTED THIS TABLET IN GRATEFUL RECOLLECTIONS OF THE DISTINGUISHED KINDNESS, ZEAL AND ABILITY WITH WHICH HE DEVOTED THE BEST PORTION OFHIS LIFE TO THEIR MORAL AND INTELLECTUAL IMPROVEMENT.

HE WAS BORN AT TIVERTON MAY 14th 1779 AND DIED IN THIS TOWN AUGUST 15th 1845

The School on the Mount

John Lansey (c1769-1825) who was appointed in 1810, was Bridgwater born and bred.[9] He and his wife Elizabeth were raising a large family of children in Bridgwater when he took on his new role and John already had probably twenty years of experience as a teacher. The Trustees may have permitted the schoolmaster to have additional fee-paying pupils.

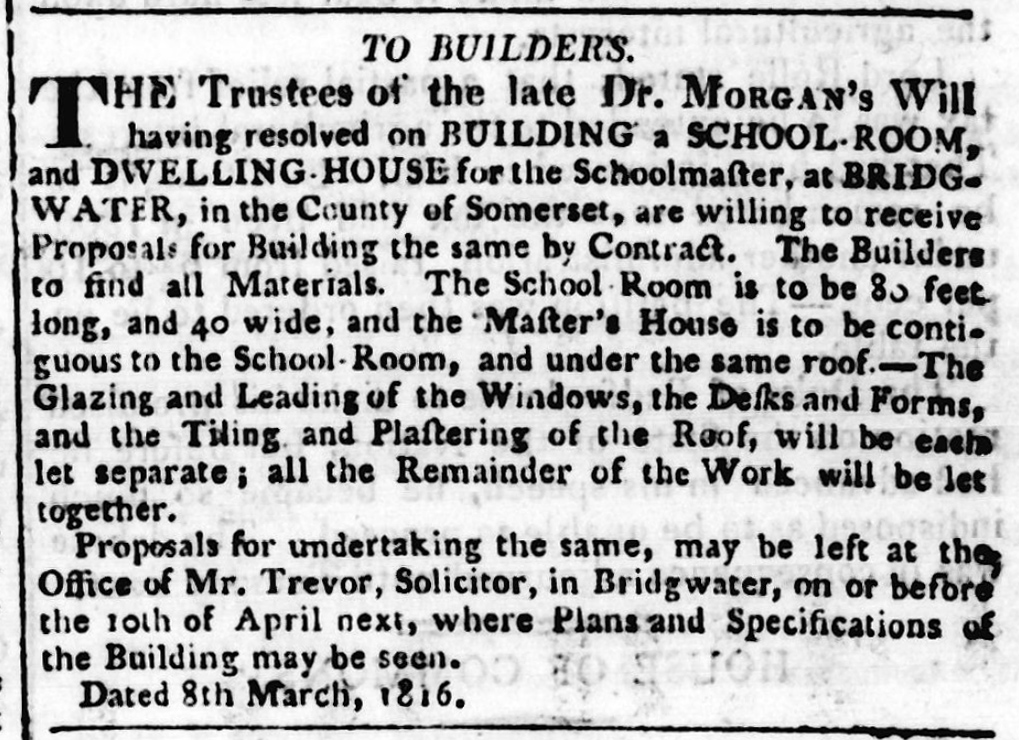

Dr Morgan’s Trustees moved the school in about 1816 to a new building in Mount Street. Now there was a spacious schoolroom and a house for the schoolmaster and his family. It was sometimes called the Free School, but rather than say ‘Charity boys’ the thirty Dr Morgan’s pupils were referred to locally as ‘foundation boys’ and Bridgwater considered them lucky have won the equivalent of scholarships. In 1819 Dr Morgan’s school had 300 pupils, which was a huge increase.

John Browne (1793-1872) brick and tile manufacturer and five-term mayor, recalled the following many years later. The other school referred may have been the King James Grammar School or the master’s own private school:

“When Mr Gill had the management of the school he had, in addition, another school for which a higher price was paid. So it was with Mr. Lansey, who only had accommodation for a very few boys besides the foundation boys. A large sum had accumulated from the rents and revenues of this estate, and some gentleman of the town thought that it would be advisable to build the present school with a view to accommodate nearly two hundred boys, certainly intending that the school should receive a poorer class.” [10]

Solicitor Joseph R. Poole (1774-1843), a two-term mayor, spoke at a public meeting in 1836 and reminded the other men present about Dr Morgan’s trust or foundation in 1816:

“The old corporation about that time reformed themselves, for then it was that they built a dwelling-house for the master of Morgan’s school and an extensive school-room for the boys. Rules were then laid down for the management of the school, which were so framed as entirely to exclude the influence of private or party feelings. About thirty boys were clothed and educated on the foundation free of expense to their parents and an unlimited number were admitted into the school, who paid the small sum of three pence a week for their instruction. As vacancies from time to time occurred among the charity boys they were filled up from the boys who had paid for their instruction, and those boys being eligible in other respects were invariably preferred who had been most constant in their attendance and who had made the greatest proficiency in learning. It was indifferent to the trustees what were the political opinions of the parents of the children and that was a circumstance never enquired into by them. “Upon these principles” Mr Poole continued, “the school has been conducted during the last twenty years …” [11]

John Lansey died aged 56 and was buried at St Mary’s Bridgwater in November 1825.

The era in which schools would remain much the same as they had been for decades, if not centuries, was nearly gone. Many people in England were illiterate. A little over half of the male population could sign their names and less than half of the women. Nationally there were calls for reform, as there were not enough schools where they were needed and many poorer children did not go to school at all. Their only hope of an education was at Sunday School. There were already other schools in Bridgwater, for instance the King James Grammar School, Thomas Gill’s school and other small, private schools for both boys and girls, but these were catering to better-off families who could afford the 4d or so a week per child. There were boarding schools in other towns, but that option involved even more expense.

King James Grammar School or The Free Grammar School

This school was separate from Dr Morgan’s but both were boys’ Church of England schools in Bridgwater. For many years they both had only one master each. The presence of the King James Grammar explains why Dr Morgan’s School did not need to educate boys for university.

The school was founded with a Royal Grant from Queen Elizabeth I in 1561, but when King James confirmed the grant in 1612, it was politically sound to name the school after him. In the 19th century the school was in a central location, such as King Square and Castle Street, and provided a classical education to the sons of well-to-do farmers and merchants for instance. The core subjects were English grammar, Greek, Latin, mathematics and Bible studies. The aim was to prepare boys for Oxford and Cambridge. While Dr Morgan’s was an endowed school with Trustees, the master of King James Grammar was responsible to the Borough of Bridgwater.

The exact location of the school in King Square is uncertain, but an advertisement for the lease of a house in nearby Castle Street in 1817, which had been used as a boys’ school for thirty years by a clergyman who taught the classics, is an example of the kind of property required.

“A commodious house … on the ground floor there are two parlours, a breakfast-room, hall and kitchens; the bedrooms are airy and spacious and they have been found sufficient to accommodate upwards of fifty pupils; the school-room is detached from the house, but it is connected to it by a high wall that surrounds the courtyard.” [12]

The annual salary of the schoolmaster was only modest, but he could augment this with fee-paying students. Fifty boys in the one house sounds excessive and may have been an exaggeration or perhaps some of the fifty were actually day boys.

The following eight men were all schoolmasters of King James Grammar between 1809 and 1869.[13] All but Julius Miles were clergymen and all but Rev. Dawes are known to have graduated from Oxford or Cambridge. They were part of the network of clergymen in and around Bridgwater who assisted each other at church services and met at parish and diocesan functions. The teaching at King James Grammar was similar to Church of England grammar schools in other parts of England and changed little over the sixty years, even though educational reform was coming.

Rev. Caleb Rockett M.A. (1766-1837) took over from Rev. Richard Jenkins in April 1810.[14] Caleb was born in Honiton, Devon, and was master from 1810 to 1819. At the same time, he was successively the vicar of Westonzoyland, Timberscombe and East Brent. Vicars of small rural parishes, like curates, often had a second job teaching. Rev. John Dawes (c1778-1838) was appointed curate to Caleb’s son at Westonzoyland and master of King James Grammar on the same day in January 1820.

Rev. James Henshaw Gregg B.A. (1802-1834), from London, was appointed master in March 1826 and was ordained the following year. He was vicar of Durleigh until his death in 1834 and is buried in St Mary’s churchyard, Bridgwater. His successor Rev. Thomas Gilbert Griffith B.A. (c1797-1855) was also from London. He arrived in early 1835 and stayed for about two years.[15]

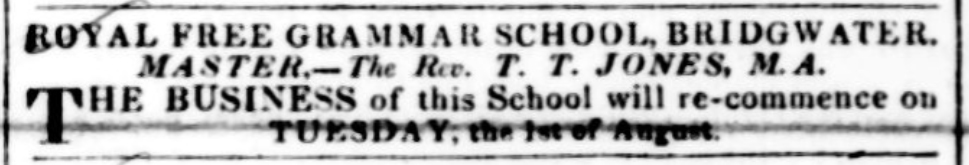

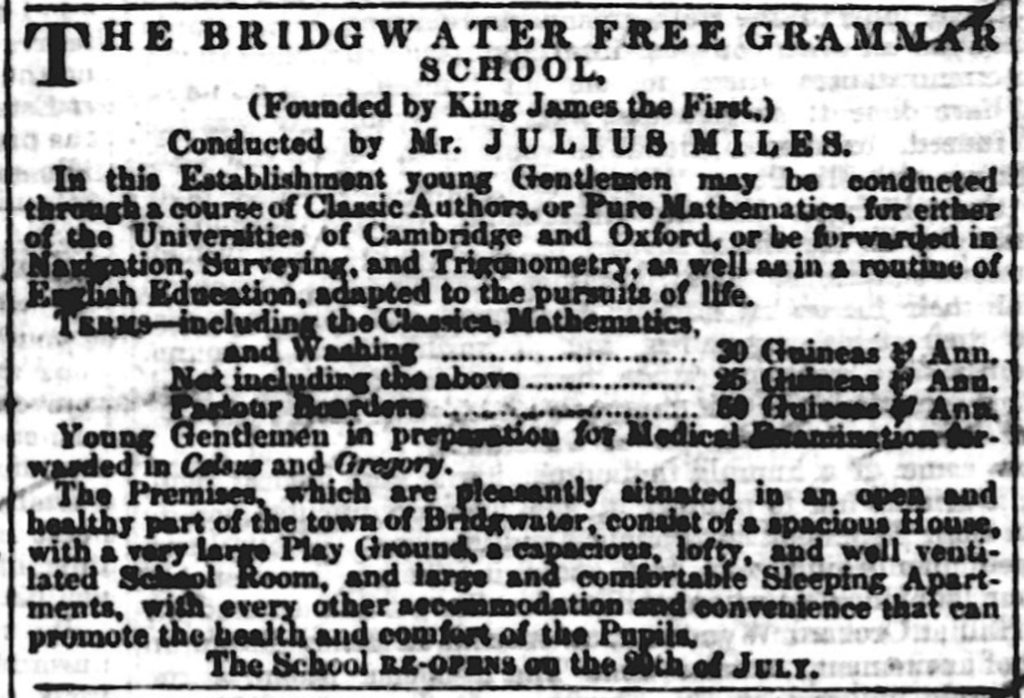

Rev. Todd Thomas Jones M.A. (c1806-1854) from Exeter was appointed in 1837 but left in 1839 after conflict with the new Trustees. He became vicar of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.[16] Julius Miles B.A. (1811-1894) followed in early 1840. Julius left Bridgwater either in 1845 or 1847.[17]

Rev Dr Thomas A. Stantial M.A. D.C.L. (1825-1906) was born in Wiltshire, the son of a tradesman. He was probably the most scholarly master since Rev. Jenkins and added to the school’s good reputation after the shorter tenures of his immediate predecessors. He taught at King James Grammar from 1848 to 1862. He wrote his widely used ‘Test-Book for Students… Preparing for the Universities or for Appointments in the Army and Civil Service’ in Bridgwater. He was an active member of the English Church Union, which was committed to the Church of England but interpreted its teachings in a Catholic sense.[18]

The endowment of the King James Grammar was only a fraction of that of Dr Morgan’s, which partly explains why the former didn’t grow. The last schoolmaster located in the records before the school closed was Rev. Francis Cotton Marshall B.A. (1831-1910). His wife Harriet died in Bridgwater in 1864 and although Francis became a vicar in Cambridgeshire and later retired to Teignmouth, he was buried in the Wembdon Road Cemetery with Harriet.[19]

Unjust Interference of Dissenters!

It was December 1836 and the Town Council was in uproar because someone had nominated four men, none of whom were Anglican, to become additional Trustees of all Bridgwater’s charities, including Dr Morgan’s School. This was done this without a vote by the council and without the knowledge of the Town Clerk. The newly elected mayor for 1837, Robert Ford, and his Conservative supporters were furious when this was discovered and called a public meeting in the Town Hall.

It was very political. The establishment, including the wealthy landowners, were mostly Church of England and voted Conservative. Many Liberal voters were Protestant nonconformists or dissenters. The municipal reforms of 1835 had resulted in the Conservatives losing their majority in the Town Council for the first time in years. The Liberals were emboldened. The Church of England felt under attack and was afraid of losing control of religious instruction in its schools.

The municipal reforms included replacing the largely Conservative, Anglican trustees of charities, with more representative trustees chosen by the reformed town councils. In August 1836, the Bridgwater Town Council recommended eleven men to be the new trustees: seven ‘Churchmen’ and four ‘Dissenters.’ The four extra trustees gave the ‘Dissenters’ a majority. The ‘Churchmen’ quoted Dr Morgan’s will in which he stated that the master and the pupils must all be members of the Church of England congregation. The ‘Dissenters’ wanted the opportunity to educate their sons in the best school in Bridgwater. At the public meeting, Mr Lovibond, solicitor and Liberal supporter, admitted that the Master of Chancery had asked him for four names of men not on the Town Council. Liberal councillor John Browne defended him vigorously, suggesting that Mr Lovibond was not working alone. Despite all the angry words at the meeting, the four men were still trustees in 1838.

Trustees of Municipal Charities were now required to submit written reports to the Lord Chancellor and so in December 1838 they described Dr Morgan’s School.[20]

“The school room erected by the former trustees is excellent in situation, well ventilated, and would accommodate 300 boys and although the attendance has increased during the past year, yet the average number has not exceeded 90 boys. The funds for the support of the school arise from the rents of an estate at Hoccombe which are not more than sufficient to educate and clothe the 30 boys now on the foundation, and to discharge the incidental expenses of the estate, school house, and playground; the other boys in the school are the pupils of Mr Jennings, who has been permitted to receive 3d a week from each boy for his education. The course of instruction in the school is English reading, grammar, writing, arithmetic, and geography; and those boys who are intended for the sea service are also instructed in mathematics, geometry, trigonometry and navigation. The school has been regularly visited during the past year and the classes have been examined occasionally and it affords the trustees much pleasure to express their approbation of the manner in which the school has been conducted and of the progress of the boys.”

The master was ensuring that the thirty “foundation boys” went to church every Sunday. The Trust paid St Mary’s the usual rent for the pews in which the boys sat each week. The Trustees requested permission for the school to give a discount to boys who were recommended by the burgesses of the town. The master, Mr Jennings, received a salary of £40 p.a. paid in two instalments in March and September. The schoolroom was used for Sunday School and in the evenings for adult classes. Community events were sometimes held in the schoolroom and school grounds, for instance when the children of Bridgwater joined in the celebrations for the coronation of Queen Victoria.

The King James Grammar School was mentioned in the same report but did not fare so well. The master, Rev. T. T. Jones, had declined to enrol four boys recommended by the new Trustees and so had lost the confidence of the Trustees. Whether Rev. Jones was acting on the instruction of the Vicar or even the Bishop is not known.

The report mentioned the incumbent master of Dr Morgan’s, Benjamin Jennings (c1793-1842), who was a teacher at Nether Stowey before he took over from John Lansey in about 1826. Benjamin, his wife Sarah and their children lived in the master’s house at Mount Street. He was described as a man of great talent, though self-taught, and one of the best Old Testament scholars in the neighbourhood. Self-taught was a polite way of referring to a humble family background, perhaps in a home where the Bible was the only book. His children were baptised at St Mary’s and he found a way of working with both the Trustees and the Vicar. His successor apparently came and went without controversy.

Bridgwater Boys’ National School

The next chapter in the story of Dr Morgan’s School began with the arrival of a new Vicar of St Mary’s, Rev. T. G. James, in 1848. To quote Bridgwater solicitor Richard Smith: [21]

When the Rev. Mr James came to town, he found no National School in connection with the Church of England for boys and he said: “Here is a fine foundation – bring them in here close.”

Rev. James wanted to educate as many children as possible and he knew that the National Society for Promoting Religious Education provided education for the poor in accordance with the teachings of the Church of England. The plan was a National School in every parish and there was government funding to achieve this. There was already a Girls’ National School in Northgate and a National Infants’ School. It was usually the local vicar who was responsible for setting up the National schools in existing premises such as a Sunday School. Dr Morgan’s School was an elementary school with not enough pupils to fill its schoolroom so it was an obvious choice.[22]

More schools had opened in response to Bridgwater’s growing population. The British and Foreign Schools Society was a charity with similar aims, but was non-denominational. A British and Foreign school opened in Bridgwater in 1824. The Baptists, Independents and Unitarians all established schools and Sunday Schools for boys and girls. St John’s, Eastover, Church of England school was opened about 1845 for boys and girls. Sometimes this was called the St John’s parish school or the St John’s National School, Eastover. St Joseph’s Catholic school began in 1846 or shortly after. The West Street Ragged School was founded in about 1846 to educate the poorest children. They attended entirely free of charge as the teachers were volunteers. By 1846 the children resident in the Bridgwater workhouse had their own schoolmaster and schoolmistress.

Dr Morgan’s School was first mentioned in the list of schools potentially eligible for a government grant along with other National Schools in 1848, however it had not yet been inspected.[23] The administrative arrangements had begun and Dr Morgan’s School became a Boys’ National School. The thirty boys chosen and subsidised by Dr Morgan’s Trust paid a lower weekly fee than the other pupils. The new “Scheme” didn’t please everyone and there would be more debate. The British and Foreign school had either merged or closed by 1852.

Alfred R. Mowbray (1824-1875), the son of a lace manufacturer, arrived at Dr Morgan’s as master in 1849. As his name suggests, he came from Leicestershire. Alfred had trained specifically to be a National School teacher at St Mark’s college in Chelsea and was Dr Morgan’s first ‘certificated’ schoolmaster. He had a strong connection with the Oxford Movement or High Church group of the Church of England. He had been a teacher at Bingham where he designed and helped paint a stained glass window in the parish church. Alfred only stayed in Bridgwater a short time, in part probably because the services at St Mary’s were not High Church. He became a successful stationer and publisher of religious texts in Oxford.

National Schools used the monitorial system whereby one qualified schoolmaster relied on monitors or pupil-teachers to assist him. The master had a desk at one end of a big open schoolroom, from which he could see everyone. The pupils sat at wooden desks facing their own pupil teacher, grouped by age and ability. The pupil teachers were boys in the top grades who were taught by the master, but also taught the boys in the lower grades. This was cost-efficient for the school and good training for future teachers. After five years, a pupil teacher, who would be aged about eighteen, was ready to do a two year teacher training course at Battersea College or St Mark’s College in London.

Although well-organised from the school’s point of view, the method of teaching was very rigid and was mostly by rote learning. A word was written on the blackboard, the children repeated it out loud and then wrote it down on their slates. Gradually this progressed to whole paragraphs written on the blackboard. The same words, sums and tables were repeated many times. Children were taught to write with their right hand, if necessary by tying down the left hand. Discipline was strict and boys were caned or made to stand in a corner or on a stool. There was no room for individual preferences, learning difficulties or behaviour problems. Slow learners would be kept down in a lower class and repeat offenders would be expelled.

The National Society made annual inspections and published reports. In February 1850 Dr Morgan’s Boys’ National had 125 pupils divided into six classes under a trained master, who was either Alfred Mowbray or Thomas Hyde, aided by four pupil-teachers.[24] “Discipline was very fair. The children receive oral instruction upon most subjects in their gallery of desks, the reading is taught upon the open floor in sections. The master is intelligent, working hard, and with effect. This is a very large and important school, with very good endowment. Great exertion has been lately made to procure fit and proper furniture and apparatus for the school.”

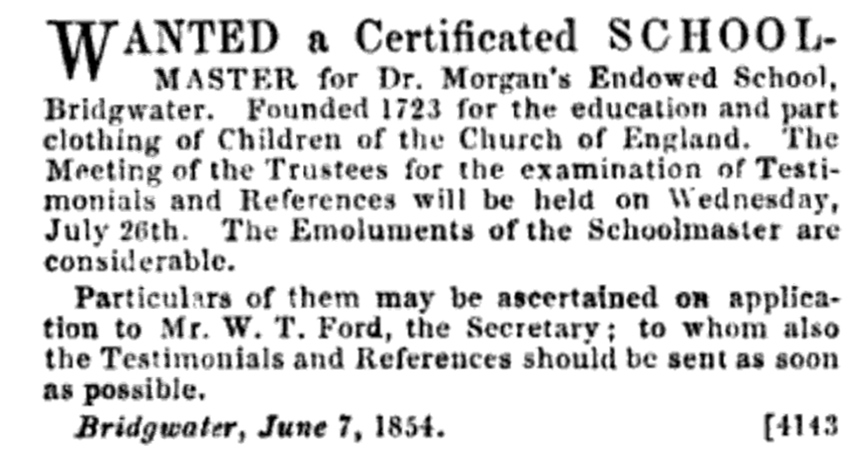

In March 1852, Dr Morgan’s Boys’ National had 137 pupils and the master was Thomas Hyde (1825-1883). He was a certificated schoolmaster from London and by the time of the inspection had been in Bridgwater for at least a year.

“There are good groups of parallel desks and the room is very fairly furnished. Apparatus fair, books required for the junior classes. A boys’ school, under a master with three apprentices. The discipline is very fair. Method may be improved. The master appears to be earnest and attentive and to have worked hard; his health not very good.”

Schoolmaster Charles Lucette

Thomas Hyde left in 1854 and Dr Morgan’s Endowed School advertised for a new schoolmaster. The successful applicant was Charles Lucette (1829-1893) an enthusiastic young teacher who was also an amateur organist and choirmaster and who participated in many parish and community events during his nearly forty years in Bridgwater. Charles was born in Ewell, Surrey, and did the two year course at the Battersea Teachers’ Training College. His first school was the National School in the village of Elson, near Gosport. He was well-trained and stayed for the rest of his career. He provided some stability for the school during the years of educational reform.

When Charles Lucette first arrived in Bridgwater, some of the boys he taught and their families still had memories of Dr Morgan’s school and its traditions. Some of Bridgwater referred to the school as the National and at the same time, others called it Dr Morgan’s. This was not resolved for another twenty years. Charles was answerable to the Trustees, to the National Society and their inspectors, but also to the vicar of St Mary’s. This was initially Rev. T. G. James, but primarily Rev. M. F. Sadler for eight years, followed by Rev. W. G. Fitzgerald. Charles was keen to help out the Vicar when requested. Early on they both gave an evening per week, unpaid, to run evening classes for adults at the school. Charles taught arithmetic, algebra and English grammar and Rev. Sadler lectured broadly in Holy Scriptures, history and geography.

The children, like all schoolboys, enjoyed a break from the monotony of lessons. In August 1854 there were celebrations in Bridgwater for the opening of the exhibition in support of the restoration of St Mary’s Church. The pupils of Dr Morgan’s school and King James Grammar led the choir, the Mayor, the Bishop, the clergymen, town councillors and all the dignitaries in procession from the Mayor’s house to the Assize Hall. “It was an occasion of such gaiety and animation as we have scarcely ever before witnessed in this ancient county town.” [25]

In December 1855 plans were drawn up for alterations or extensions to the school.[26]

Debate and Reminiscence

The original schoolroom of the West Street Ragged School had become too small for the growing number of children attending. Bridgwater was eligible for a government grant to build a new, bigger school, on the condition that it became a day school and employed a trained schoolmaster and schoolmistress. Accordingly, the West Street School for boys and girls opened in 1860 in a new schoolroom with a fee of either 1d or 1½ per week and the Ragged School children were taught in the evenings and on Sundays by volunteers.

Social status was incredibly important to Victorian society and many held the now outdated view that the father’s occupation should determine the kind of education provided to his children. They also believed that poor people were to blame for their circumstances, which again is very harsh by today’s standards. The West Street School was a new option for the children of Bridgwater’s workers and the Trustees of Dr Morgan’s School wanted to raise the weekly fee at the combined Dr Morgan’s Boys’ National School to improve the school’s finances and also reposition it as a middle-class school for the sons of skilled tradesmen and shopkeepers.

A special meeting of fourteen Trustees, including Mayor Robert Ford, was held in the Clarence Assembly Room in October 1860. The men debated for and against raising the weekly school fee from 3d to 4d. The biggest single group who would likely be excluded were the children of the brickyard workers who were laid off in winter when the clay was frozen. The St John’s National School in Eastover which charged 2d or 3d per week was another alternative for those families. Some trustees recalled their own schooldays.

George Parker (a historian of Bridgwater) said:

“Fifty-two years ago the school was held in the Square, and Mr Gill had the management of it, and a better master of a commercial school than Mr Gill they never had. With Dr Morgan’s boys Mr Gill had a number of most respectable tradesmen’s children. When Mr Gill gave up Mr. Lansey had it and conducted it in the same manner. He was talking to a person a day or two ago who was then at the school, and was now a respectable tradesmen of the town. The children then paid sixpence per week. Mr. Lansey also took boarders and during the time he had the school, public attention was called throughout the country to the necessity of a better education for the children of the lower classes. A great commotion was made in the country about the matter and near that time the trustees built the large school room on the Mount, no doubt for the purpose of accommodating that class of children, because at that time there was no other school capable of receiving them in the town.”

Richard Smith junior:

“He, Mr Smith, attended the school when Mr. Lansey had it, and his father paid sixpence per week for him when he was a little boy. His sisters went there also. He stayed there a little while, and then went to another charity school, where he finished his education. It was one of the proudest things he could boast of and he had a feeling for charity boys. … The boys at Dr Morgan’s school receive an education which he and those present never did receive and never could get – almost a first class education.”

Rev. Mr Collins:

“Fifty-five years ago Mr Gill had the management and not only educated some of the chief inhabitants of the town, but the present recorder of Bridgwater was one of his pupils, boys receiving a good education from him.”

The resolution was passed and in 1861, other than for the ‘foundation boys’ it cost 4d per week for a child to attend the school.

School Boards and Dr Morgan’s in the Spotlight.

Previous attempts to reform the nearly three thousand grammar schools and endowed elementary schools across the nation had been unsuccessful due to the irreconcilable political differences between the Church of England and the nonconformists. Somehow the government had to break this deadlock. Some of these schools were providing a free, classical education to upper and middle class children while working class children missed out altogether. Schools for girls were limited and there were areas without any schools at all.

The Endowed Schools Act of 1869 resulted in all the specific religious conditions of Dr Morgan’s will, such as church attendance, being repealed and replaced with a general statement that the school must be conducted in accordance with the principles of the Church of England. The Trustees were replaced by a Board of Governors. The Endowed Schools Commissioners published their report with the new ‘Scheme’ for Dr Morgan’s in detail early on so that other trustees in England could use it as a template for what might happen in their own schools. “No stronger case of a school tied up in every possible manner to the Church by its founder could be cited.”[27] There was strenuous opposition from the Trustees. There were also upper limits on school fees and the boys were to be at least seven years of age and no older than fourteen. The new Dr Morgan’s Board of Governors would consist of fourteen persons, men or women:

- 6 ex-officio: the Mayor, the three vicars of Bridgwater, the Archdeacon of Taunton or his representative; the chairman of the School Board.

- 2 elected by the Town Council

- 2 elected by the School Board

- 4 co-optative – the former Trustees – Carey B. Mogg, George Parker, Gabriel S. Poole of Brent, John L. Sealey, Joseph R. Smith, John Trevor – but when by natural attrition there are less than four co-opted trustees, the Board of Governors can choose others.

In the first year, the mayor, the chairman of the School Board and the four elected or representative members were all non-conformists.

The Bridgwater School Board had been created by the Elementary Education Act of 1870. For the first time there was a local body which had the authority and the funds to build non-denominational schools where they were needed and in Bridgwater they set about building a new school at Eastover.

Another major outcome of the new acts and of an 1869 report on the grammar schools of Somerset was the closure of the King James Grammar School. There were only thirty day boys, the school was conducted in a private home and would have needed more funding to continue.[28]

Dr Morgan’s School Reclaims Its Name

With the coming of local school boards and associated changes in government funding, National Schools generally became board elementary schools. The Bridgwater Boys’ National was once again Dr Morgan’s School and the Girls’ National became St Mary’s Church of England School.

In 1872, the Endowed Schools Commissioner informed the Trustees of Dr Morgan’s School that the Board would now provide elementary schools and that Dr Morgan’s School should become a ‘third grade’ secondary school for boys with a leaving age of 14 or 15. It would teach modern subjects like French, history, geography and science, to boys who were expected to become small tenant farmers, small tradesmen or superior artisans. ‘Second-grade’ schools taught middle class boys to the age of 17 or 18 the subjects they needed for the army and the civil service and ‘first-grade’ schools focused on preparing upper class boys for university.

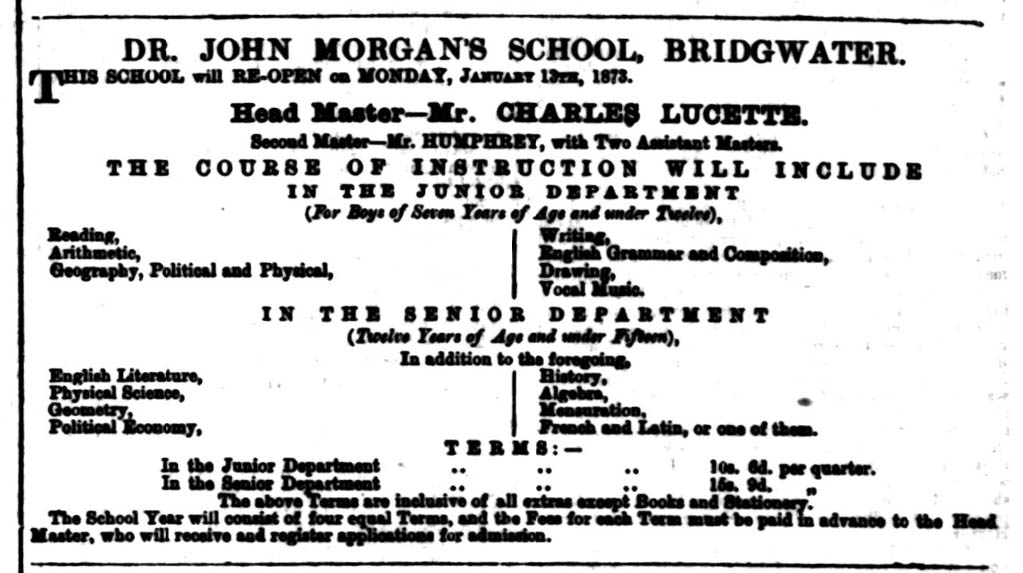

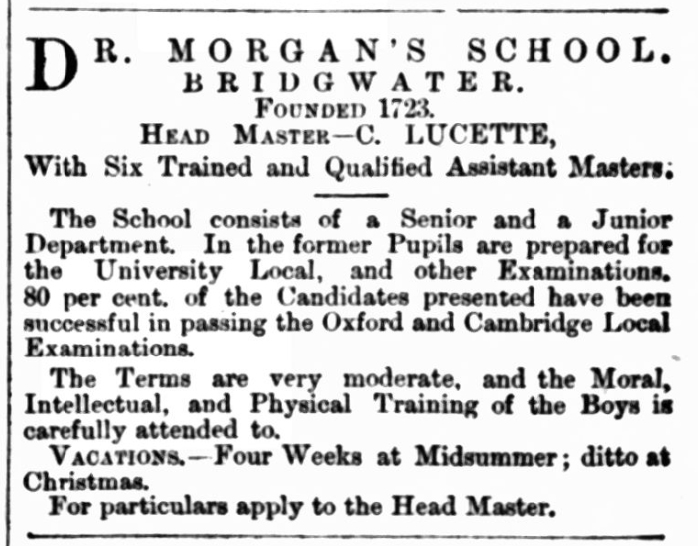

It was hotly argued. The Church of England did not want to give up its premier boys elementary school in Bridgwater nor the right to educate boys in the Church of England faith. Somehow a compromise was reached. The Junior School remained. The following advertisement is from the Bridgwater Mercury in January 1873.

Dr Morgan’s was no longer a charity school and boys over eleven had to sit an entrance examination for the senior school. The headmaster was responsible to the Board of Governors and the boys wore dark suits instead of the original blue. Within a few years the school was accepting boarders as well as day boys. Additional schoolmasters were employed to help teach the wider range of secondary school subjects, though Charles Lucette may have continued to teach ‘vocal music’ himself.

The Diocesan Inspector, a clergyman, visited the school annually to compile a detailed report for the Bishop. All academic subjects and classes were reviewed. The inspector not only read through the written examination papers, but also went to the junior and senior schoolrooms and tested the boys himself by asking questions. In January 1877 the speech night was reported in the Somerset County Gazette, including the 1876 Diocesan Inspector’s report, which was read out to the mayor, the dignitaries, parents and boys. The Inspector was pleased that in Old and New Testament, grammar and geography, the boys answered readily and accurately. Their knowledge of French was not as good. The senior class had studied Shakespeare’s Richard III and the exam papers showed that all the boys were able to relate the plot, explain allusions and difficult phrases. Results of the examinations of the most senior boys in algebra and geometry were very good overall and the headmaster’s son, C. E. Lucette, was top of the class. The Diocesan report concluded by congratulating the school and all those connected with it.

“The papers of many throughout all the subjects are remarkable for knowledge of the subject and for accuracy, clearness and readiness of expression.”

The school was functioning well.

In 1880 there was a further act of parliament and education became compulsory for every child to the age of ten years. Not every school could survive the years of political debate and reforms, but Dr Morgan’s was fortunate that back in 1816 the Trustees had the vision to build the large schoolroom. As a result the school could be more flexible and respond to change.

Reforms and improvements continued. Nationally the school leaving age was raised so that children remained at school until they were of an age to legally go to work. Schools were inspected regularly and over time, teaching methods improved and the subjects taught were modernised when necessary.

Headmaster Charles Lucette died in 1893 and was succeeded by his son, Rev. Charles Edward Lucette. Dr Morgan’s School was now well-established and recognisable as the school that continued into the 20th century.

by Jillian Trethewey and Clare Spicer 22/1/2025

Bibliography

A P Baggs, M C Siraut, ‘Bridgwater: Education’, in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 6, Andersfield, Cannington, and North Petherton Hundreds (Bridgwater and Neighbouring Parishes), ed. R W Dunning, C R Elrington (London, 1992), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol6/pp238-241 [accessed 12 January 2025]. Bridgwater: Education | British History Online

Kerr-Peterson, Miles. Dr Morgan’s School Mount Street. Bridgwater District Civic Society website. https://bridgwatercivic.org.uk/blue-plaques/dr-morgans/

Clergy of the Church of England database. CCEd | Clergy of the Church of England Database

Friends of Wembdon Road Cemetery website. Welcome – Friends of the Wembdon Road Cemetery for biographies of headmaster Charles Lucette and others.

Lawrence, Dr Chris. A Brief Note on John Morgan’s School and Bridgwater’s other Grammar Schools. seen in Old Morganians Newsletter No. 11, October 2015. Editor: Geoff. Marchant.

Lawrence, J.F. & J.C. A History of Bridgwater. Phillimore & Co. Ltd. 2005

National Society. Thirtieth Annual Report of the National Society. London 1841. Seen online bound in a volume with later Monthly Papers of the National Society. THIRTEITH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE NATIONAL SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING – Google Books

Slater, Isaac. Slater’s (late Pigot & Co.) Royal National and Commercial Directory and Topography of the counties of Berkshire, Cornwall, Devonshire, Dorsetshire, Gloucestershire, Hampshire, Somersetshire, Wiltshire, and South Wales … [1852-53], seen on the University of Leicester website. Slater’s Directory of Berks, Corn, Devon …, 1852-53 – Historical Directories of England & Wales – Special Collections

Spicer, Clare. 1860 and the Future of Dr Morgan’s School. 2021. Bridgwater Heritage website.

Spicer, Clare et al. The West Street School and Ragged School. 2021. Bridgwater Heritage website.

Squibbs, P.J. Squibbs History of Bridgwater. Phillimore. 1982. Chichester.

[1] Lawrence, Christopher. A Brief Note on John Morgan’s School and Bridgwater’s other Grammar Schools. (see bibliography.) This is the source of information about Dr John Morgan and schoolmaster Richard Jenkins.

[2] Some charitable schools were called Bluecoat Schools because the pupils were provided with blue uniforms.

[3] Dr Morgan’s Will was submitted for probate to the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PCC) in 1726 so a copy was preserved in The National Archives. It has been digitised and can be viewed online.

[4] The Church House became the Mansion House Inn. Lawrence’s History of Bridgwater, page 62.

[5] Rev. Richard Jenkins Runwa Jenkins B.A. M.A. D.C.L. (1763-1823) was the son of William Jenkins, an exciseman. Richard was a graduate of Corpus Christi College, Oxford. He was a Freemason in Bridgwater from 1789 and later a member of the Common Council. Richard left to be a curate in Lee, Kent, and then rector of Axbridge, Somerset. He was buried at Axbridge in October 1823.

[6] Thomas Gill married Ann Crandon in 1803 at St Mary’s Bridgwater and had several children.

[7] Baggs, A.P. and Siraut, M.C. (see bibliography)

[8] The plaque says Thomas Gill died in August 1845, but a newspaper death notice and the Bridgwater parish register burial entry indicate it was July 1845.

[9] Lansey can also be spelt Landsey. John Landsey was stated to be of Bridgwater when he married in 1799 at Beaminster, Dorset, to Elizabeth Oliver (born c1777.)

[10] Bridgwater Mercury 31 Oct 1860

[11] Report of a meeting called in response to a hand bill headed ‘Unjust Interference of Dissenters with Church of England Charity Funds. Bridgwater 6 December 1836.’ Dorset County Chronicle 15 Dec 1836. Joseph Ruscombe Poole (1774-1843) a solicitor, was mayor of Bridgwater in 1820 and 1832.

[12] Sherbourne Mercury 20 Oct 1817

[13] The Clergy of the Church of England Database lists a few of the early schoolmasters prior to 1790.

[14] Caleb Rockett (c1766-1837) was the son of Caleb Rockett, apothecary, and Susannah. He was vicar of Townstall, near Dartmouth, before coming to Somerset. His wife was Agnes nee Buller of Nether Stowey. Their son Caleb Rockett (1803-1842) was also a clergyman.

[15] Rev. Thomas Gilbert Griffiths (c1797-1855) B.A. Magdalen College Oxford. Thomas was born in London. After leaving Bridgwater he was a curate in Devon and Worcs. He was curate at Wickham Bishop, Essex, for some years and died in Essex in 1855.

[16] Rev Todd Thomas JONES (c1806-1854) was from Exeter. He was an Oxford graduate and had taught at Taunton prior to Bridgwater. He died at Halifax, Nova Scotia.

[17] Julius MILES (1811-1894) was the son of a supervisor of excise men. In October 1845 he was an insolvent debtor in Bristol, but his daughter was baptised in Bridgwater in March 1847. The parish register records that he was then still teaching in Bridgwater. He was a schoolmaster in Bristol for the rest of his career. His sister Julia was married to Rev. William Barnes, a recognised Dorset poet and schoolmaster.

[18] Rev Dr Thomas Arthur STANTIAL (1825-1906) left Bridgwater in 1862 to become headmaster of the Ramsgate College School in Kent. He was vicar at Clapham Rise, London, from 1875 to 1884 and then vicar of St John’s Church, Bury St Edmonds from 1884 until his death. He has a biography on the website of the Bury St Edmonds church. Revd Dr Thomas Stantial – St John’s Church

[19] Rev. Francis Cotton Marshall B.A. (1831-1910) was a Cambridge graduate. He became Rector of Little Wilbraham, Cambridge.

[20] Parliamentary Papers. Accounts and Papers volume 41. 1839. Reports of the Trustees of Municipal Charities 1839. Parliamentary Papers – Google Books

[21] Richard Smith (1814-1880), brother of Mayor Joseph R. Smith. Richard was speaking at the 1860 debate.

[22] One source states that by 1839 there was a National School for Boys in Mount St with about eighty pupils, which was well before Rev. James arrived. This is likely due to confusion about the arrangements made in Mr Lansey’s time.

[23] Great Britain, Committee of Council on Education. London 1849 (became the Education Dept.)

Minutes: Correspondence and Financial Statements and Reports by H.M.’s Inspectors of Schools.

[24] For the year ending Oct 1857, Charles Lucette had three pupil-teachers: T. J. Foster, W. Barker (both 2nd year) and T.A. Manchip (1st year).

[25] Dorset County Chronicle 10 Aug 1854

[26] Somerset Heritage Centre DD/EDS/1/24

[27] Church School Endowments – Google Books

Church of England. Convocation of Canterbury, Lower House. Report of the Committee on Church of England Educational Endowments. 1872. Appendix A.

[28] The endowments of the King James Grammar School became the King James Exhibition and Scholarship Endowment Foundation. See also the Somerset Archives catalogue and Mr Stanton’s report on the Grammar Schools of Somerset quoted in the Western Daily Press 6 Feb 1869.