The Black Death arrived in England in June 1348 at Weymouth via Gascony. It reached Somerset in October and hit Bridgwater more or less immediately. There is no first hand account of the Black Death in Bridgwater, we can only get an impression via other means.

In 1917 Rev. E.H. Bates Harbin published an article looking at the spread of the contagion in Somerset (see ‘The “Black Death” in Somersetshire 1348-9’ in PSANHS LXIII, 1917).

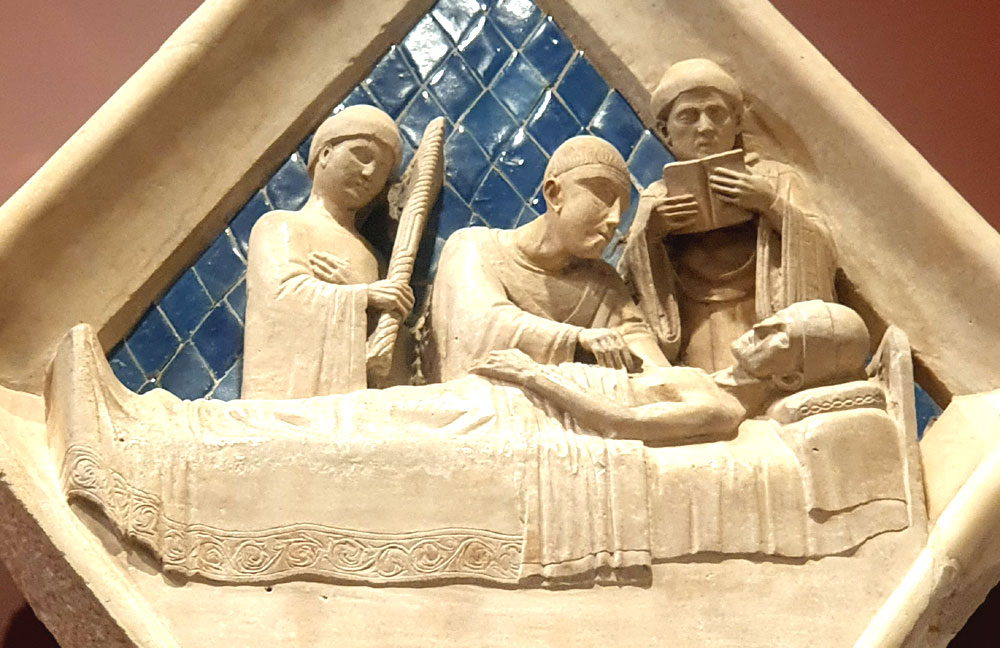

Bates Harbin traces the sudden rise in vacant church benefices (parish priests and chaplains) in the county. These vacancies were caused by the death of the previous incumbent. As priests would be called to perform the Last Rites and Extreme Unction to the dying in their sick beds, they would be directly exposed to the disease and it is therefore unsurprising that they would die in great numbers. Surprisingly though, despite the horrific casualty rate amongst the churchmen, vacancies seem to have been filled as quickly as they arose.

From a normal background average of about three vacancies per month for the county, October sees this number triple. The plague entered Somerset in two directions – over land from Dorset, and from sea via Bristol. It’s highly likely the plague entered Bridgwater via shipping in the port and river traffic from Bristol. As such, the vicar of Bridgwater was dead by the 21st October in this first wave. His name is not known. He was probably among the first infected and killed.

The unknown vicar of St Mary’s was therefore replaced with Richard of Exbridge, described as a ‘poor clerk’. He was appointed to the Vicarage of Bridgwater in November 1348. He held the living for only about four months before falling victim himself (see Vicars of Bridgwater here).

In November vacancies for the county had risen from October’s 9 to a total of 31. Yet only Woolavington in the Bridgwater area saw another vacancy, on 18 November, suggesting that alotgh Bridgwater was suffering, the town had been quarantined, buying a short reprieve for the neighbourhood. At the tail end of the month, however, Lyng fell vacant, indicating the spread to the wider district by then.

December therefore saw church vacancies rise to 46 for Somerset. The vicars had died off in Wembdon and Thurloxton by 3 December, Goathurst by the 9th and Wembdon Chantry by the 13th.

By 10 January the shortage of clergy meant the Bishop of Bath and Wells decreed that it was now acceptable that confession, one of the last rites, could be temporarily given not only laymen (ie not priests), but even by women.

January saw 38 vacancies through Somerset, and the severity around Bridgwater appears to have slackened – only one vacancy, at North Petherton, was recorded compared to four in the previous month. February and March continued the total of 38, with a resurgence in the Bridgwater area – St Mary’s Bridgwater fell vacant again by 4 March, Woolavington vicarage fell vacant again in March, then at the end of the month Charlynch and Sheerston were hit.

Only with the Spring, and the month of April did things improve, when only 17 vacancies were recorded, albeit one of these was in Puriton. By August the pestilence seems to have passed.

John Butleigh is thought to have succeeded Richard of Exbridge as Vicar of Bridgwater after March 1349. He is first mentioned in documents in the Bridgwater Borough Archives in 1355. His name appears as Vicar as late as 1363 (Vicars).

So Bates Harbin’s study gives us a suggested outline for the progress of the Black Death around the Somerset area, can we get an idea of how bad it was on the ground?

The following is a summary of the research of Francis Aidan Gasquet in his 1893 book The Great Pestilence (A.D. 1348-9), now commonly known as the Black Death, pages 168-9.

The Manor Rolls of nearby Chedzoy give a window into the extent of deaths among ordinary people. These rolls say when fines were imposed when someone took on a tenancy for a property in the manor, which would be a house with attached land or lands to work. Vacant properties will have been caused by death of the tenant, much like the church vacancies seen above. This only tells us when the tenant, i.e. the head of the household died, so we still don’t know how many additional people – wives, children, elderly parents, and servants – died as well.

The court roll for Chedzoy for 25 November show that the plague was already in the manor, with three or four large holdings having reverted to the lord of the manor, as there was no heir from the families who had previously held them to take them over. William Hammond at the Waterwheel at ‘le Slap’ was noted as killed by plague, and the mill was out of use as there was no miller available to take over. The next court on 8 January 1349 shows 20 tenants had died, with the worst peak being at the end of December. There was no let up in the following few months, the court roll of 23 March 1349 shows between 50 and 60 tenancies had ended.

The court also recorded how people came forward to act as guardians for orphaned children. John Cran is recorded as taking over the house and lands previously held by his dead father, but also agreeing to take care of young William atte Slope, whose whole family had been killed. This court also noted that a case bought before them in January, which was a dispute between John Lager on one side and William, John and Roger Richeman for the return of some cattle, could not proceed as all three Richemans had died in te intervening time. To cap things off, the scribe of the March records changes abruptly, and its not impossible to suspect they had died midway through the effort of record keeping. However, the important thing to note here is that despite the horrific extent of the plague, the courts were still functioning.

Possible plague pit sites have been suggested in Mansion House Lane and also in High Street (although that one is possibly later)

MKP 13 September 2023