A full biography of Arthur Cottam can be found on the website of the Friends of the Wembdon Road Cemetery, which has been written by Jillian Trethewey, Hilary Southall and Clare Spicer.

Arthur Cottam is buried in Bridgwater, having retired to the town to be near is son, Arthur Basil Cottam, a noted local architect. Arthur was a civil servant, with considerable scientific interests. He was born in London, but later moved to Watford, where he spent most of his life. He married Mary Gibbs in 1860. Being in Watford, he was close to the hills of Bushey Heath, the site of the Beaufoy Observatory.

Arthur was elected a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society on 14 February 1862. The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) was founded in 1820 to promote the study of astronomy. Most of its members in the early years were ‘gentleman astronomers’ meaning amateurs who had the means to set up their own telescope, spend time on their hobby and travel to London for meetings.

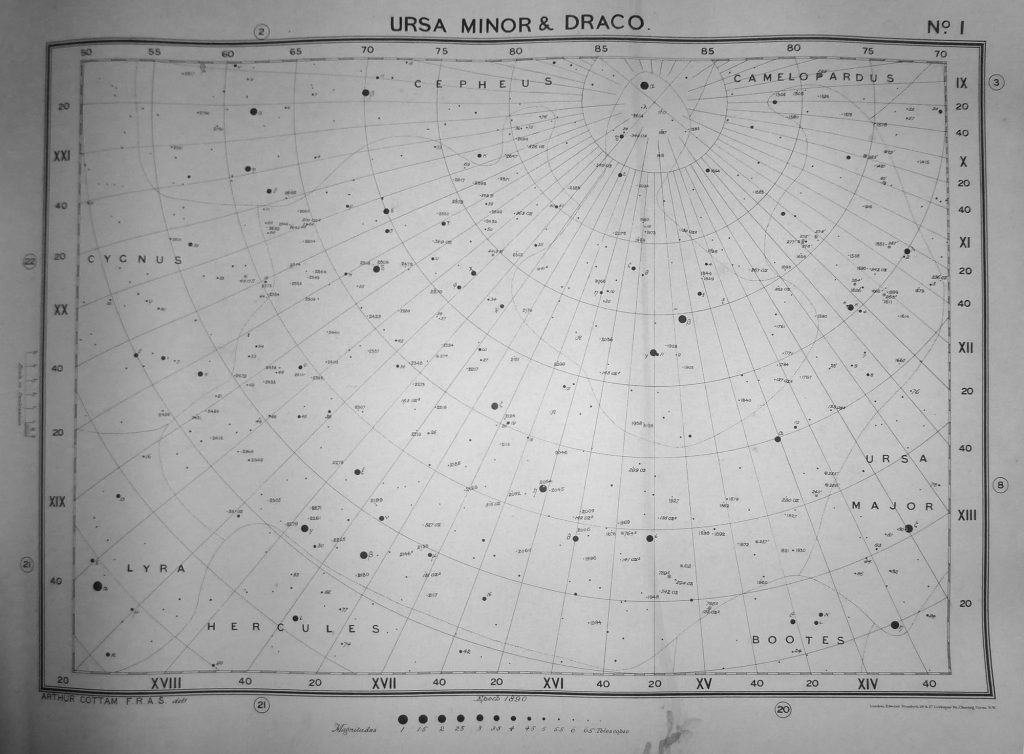

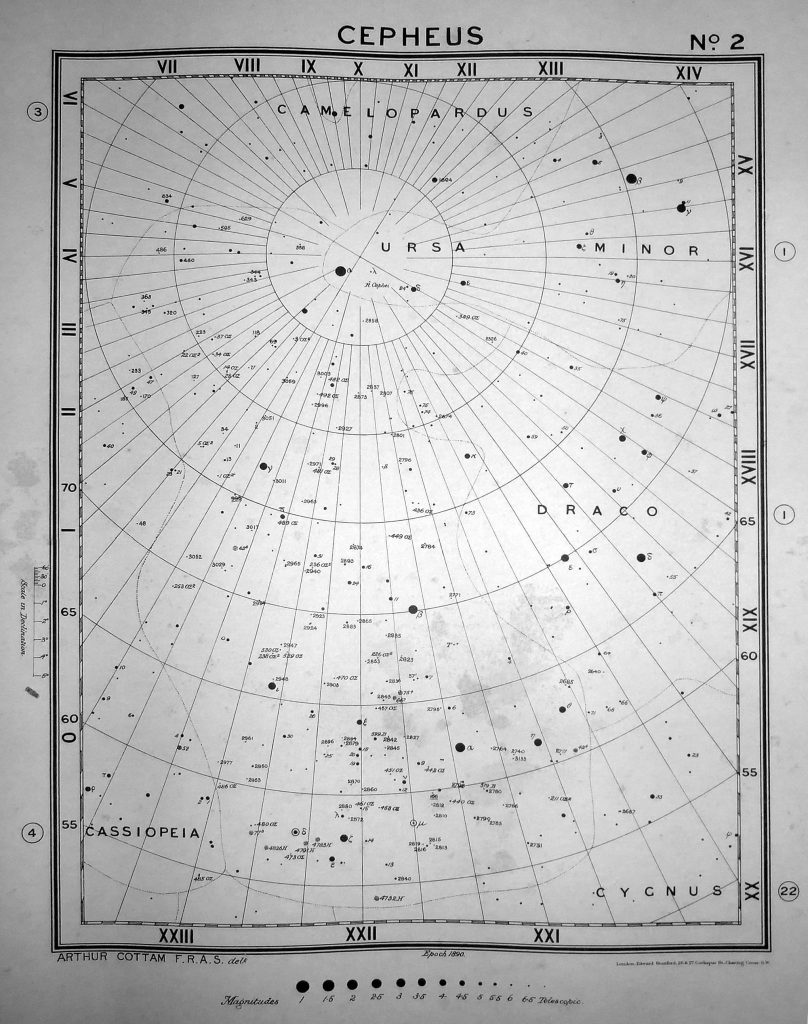

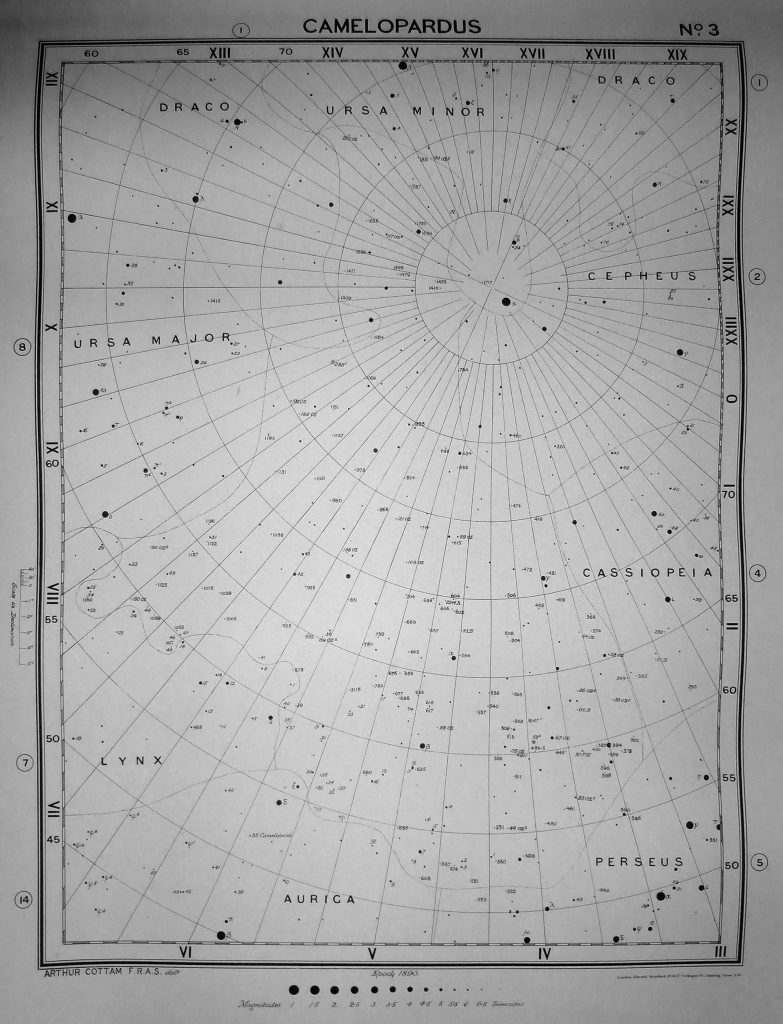

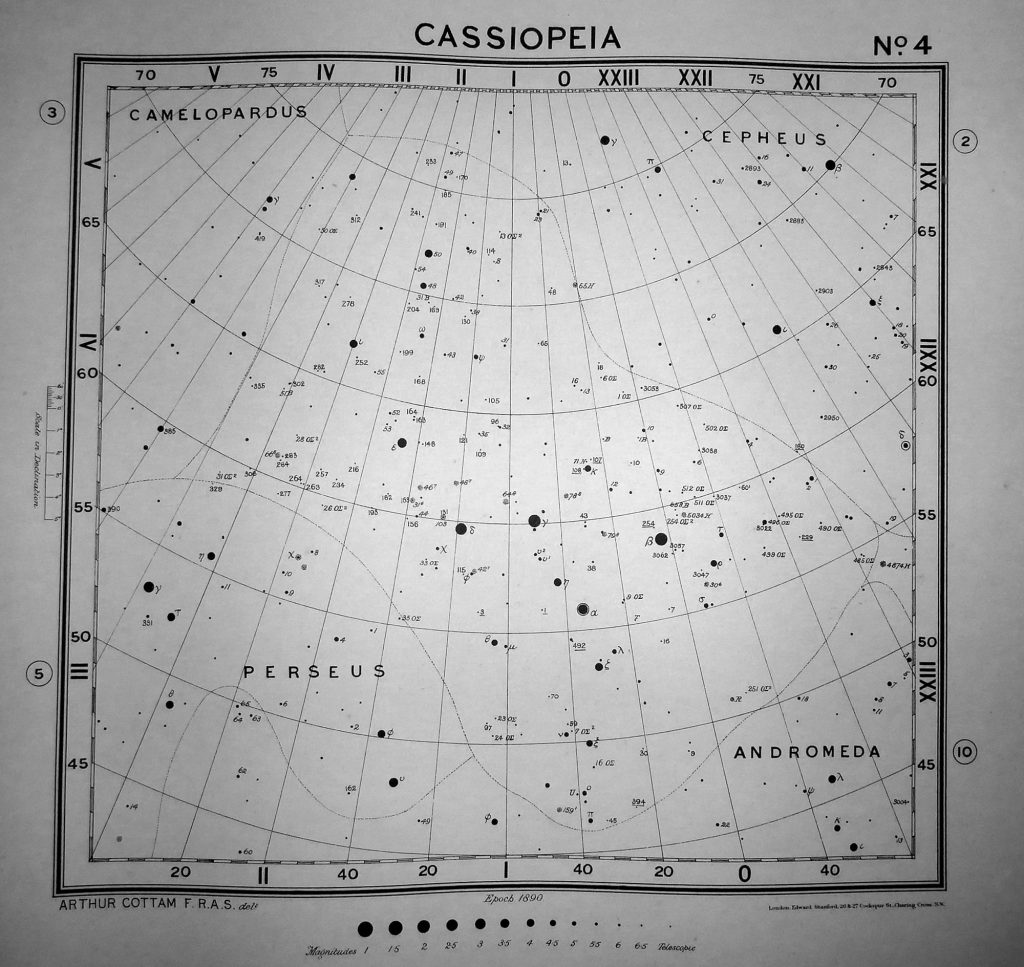

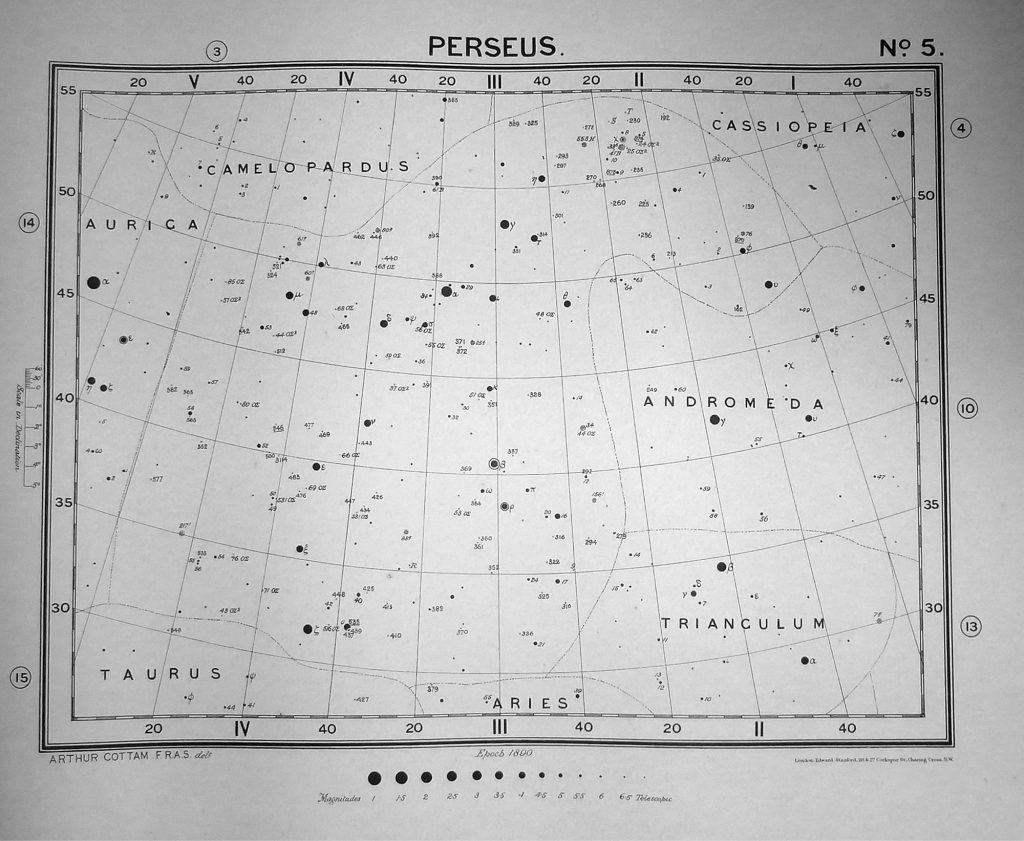

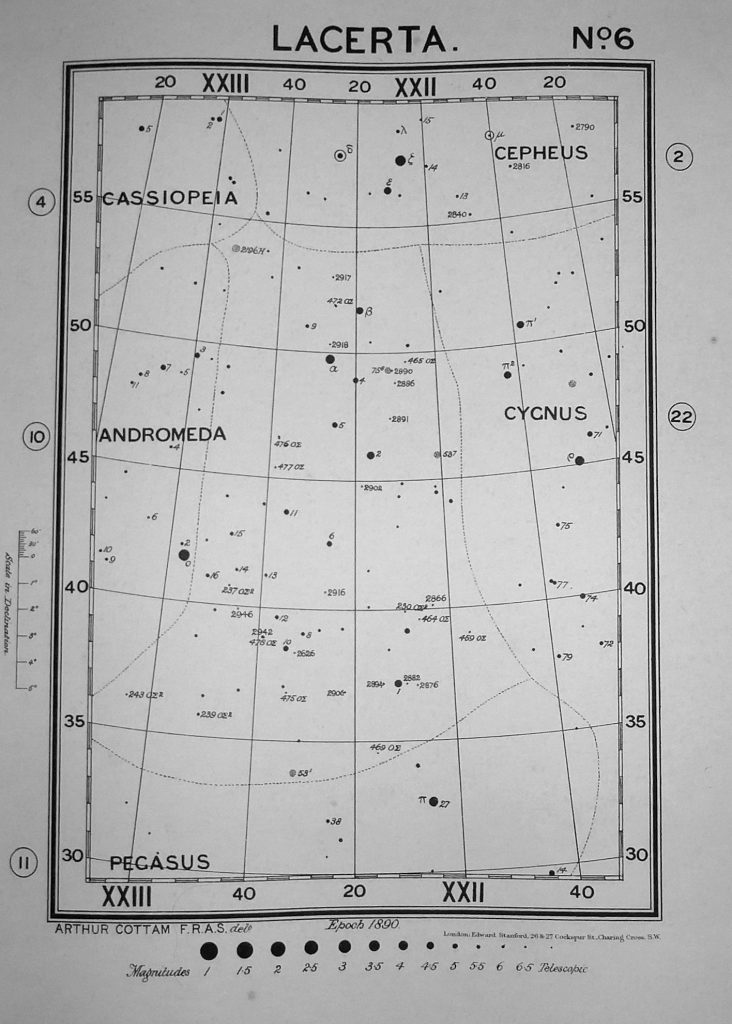

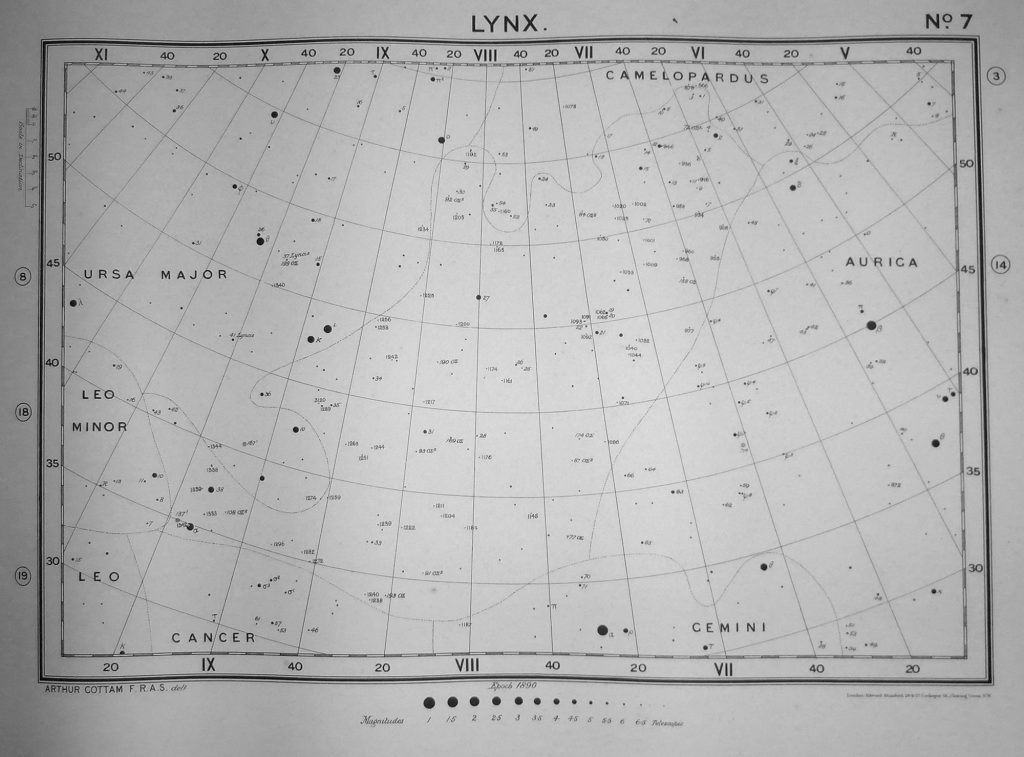

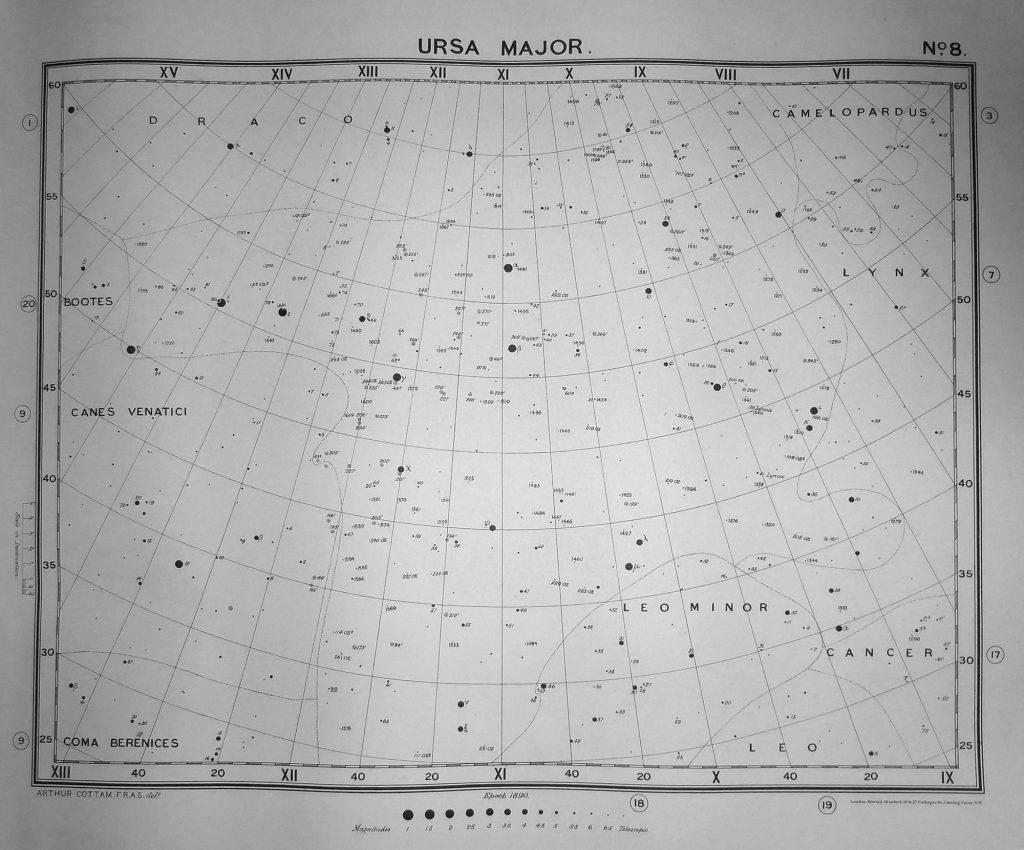

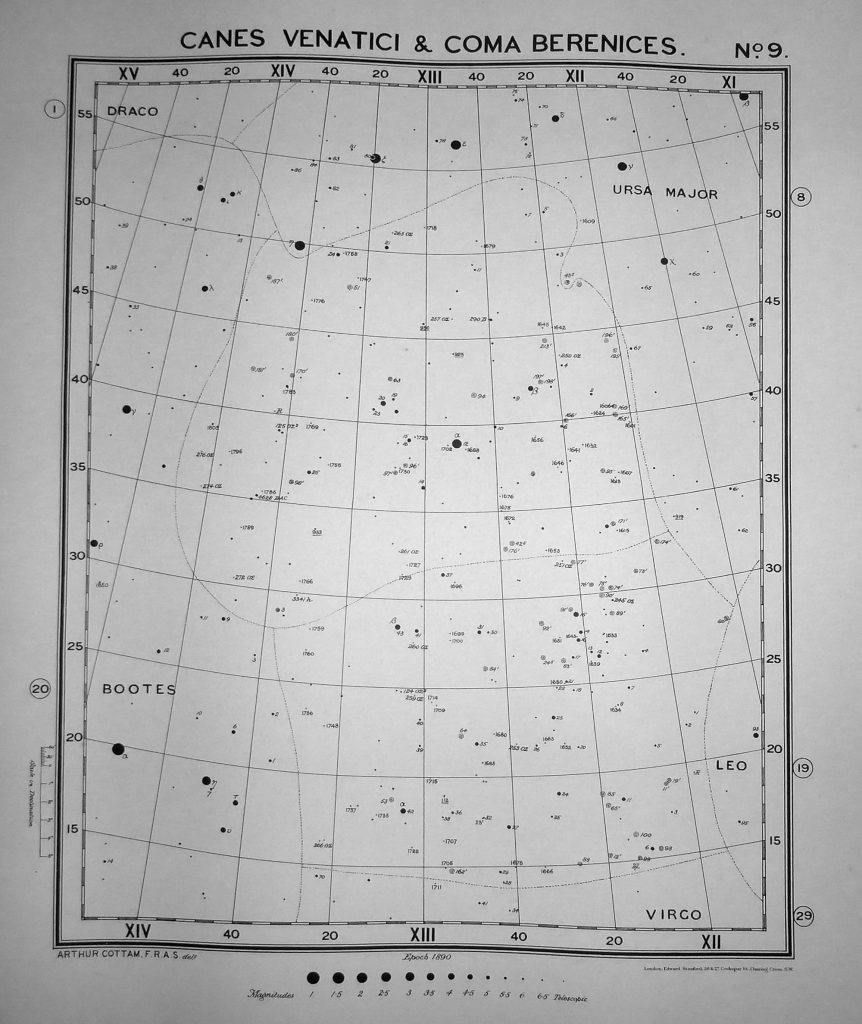

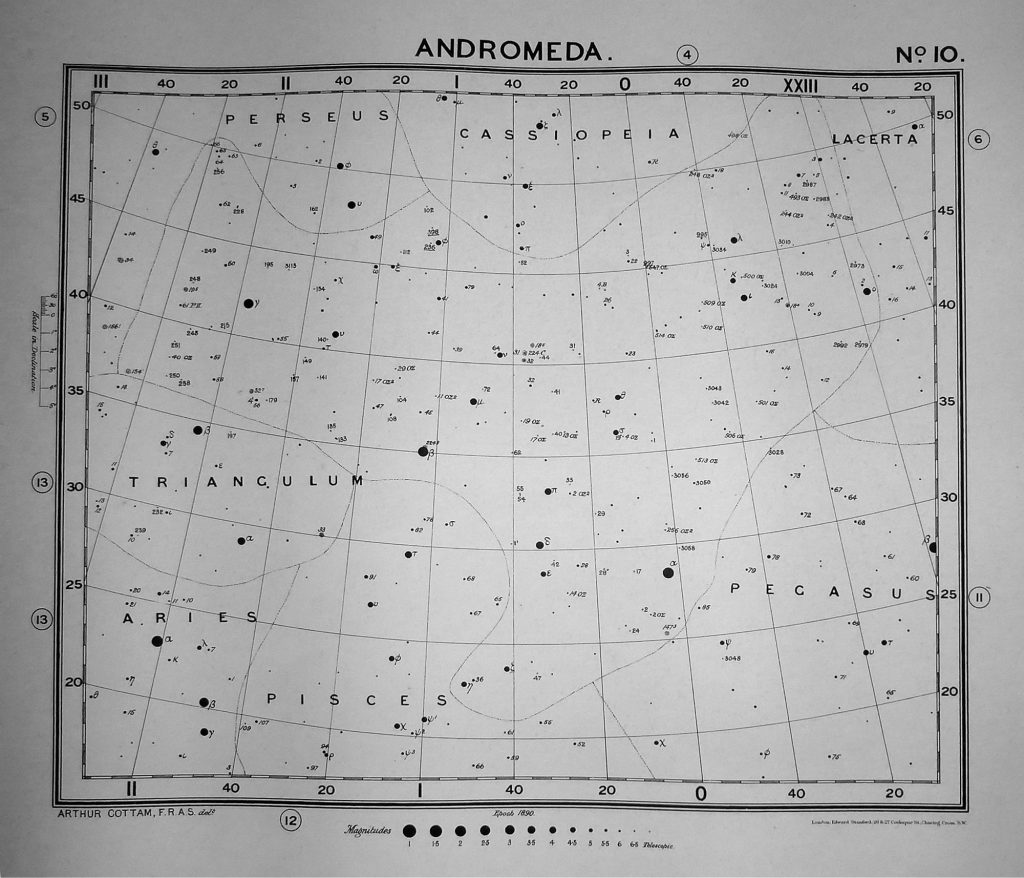

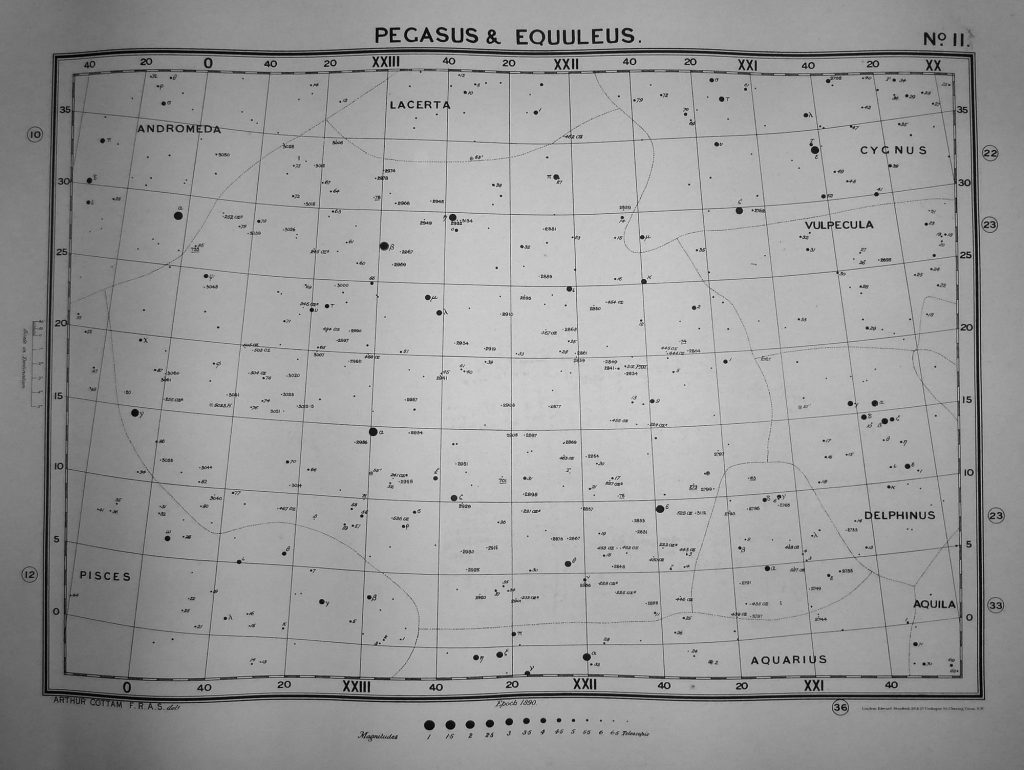

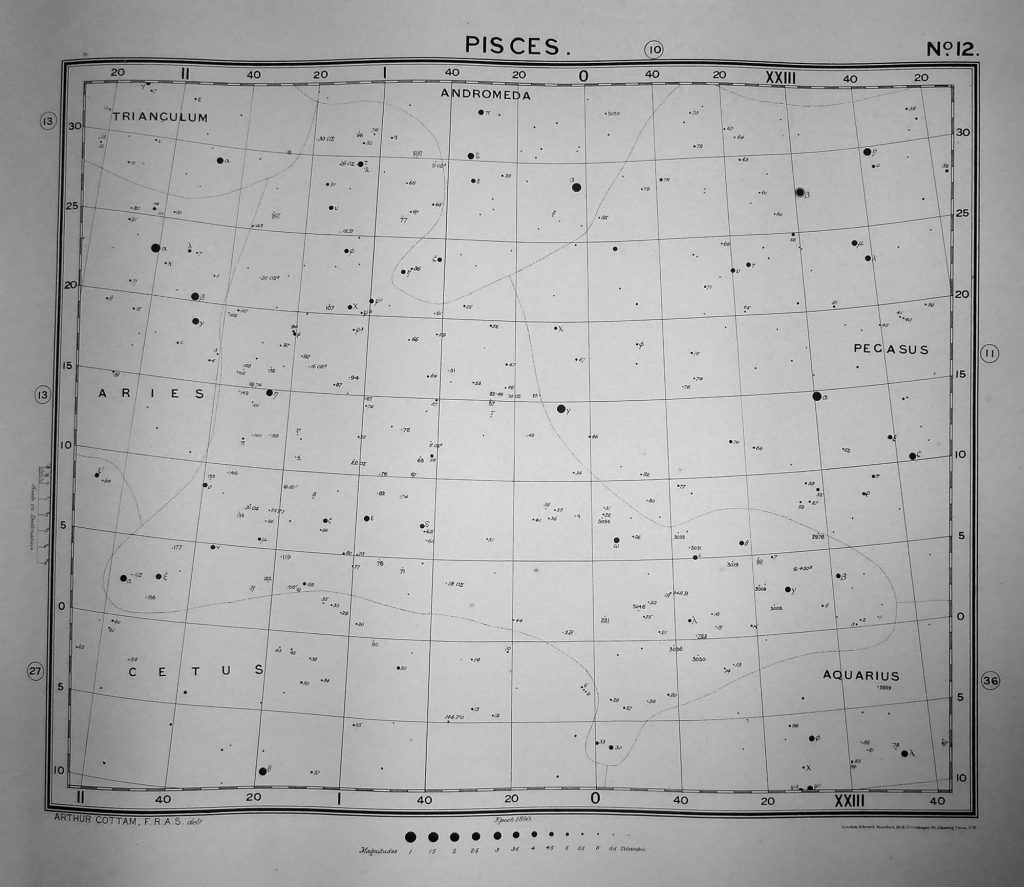

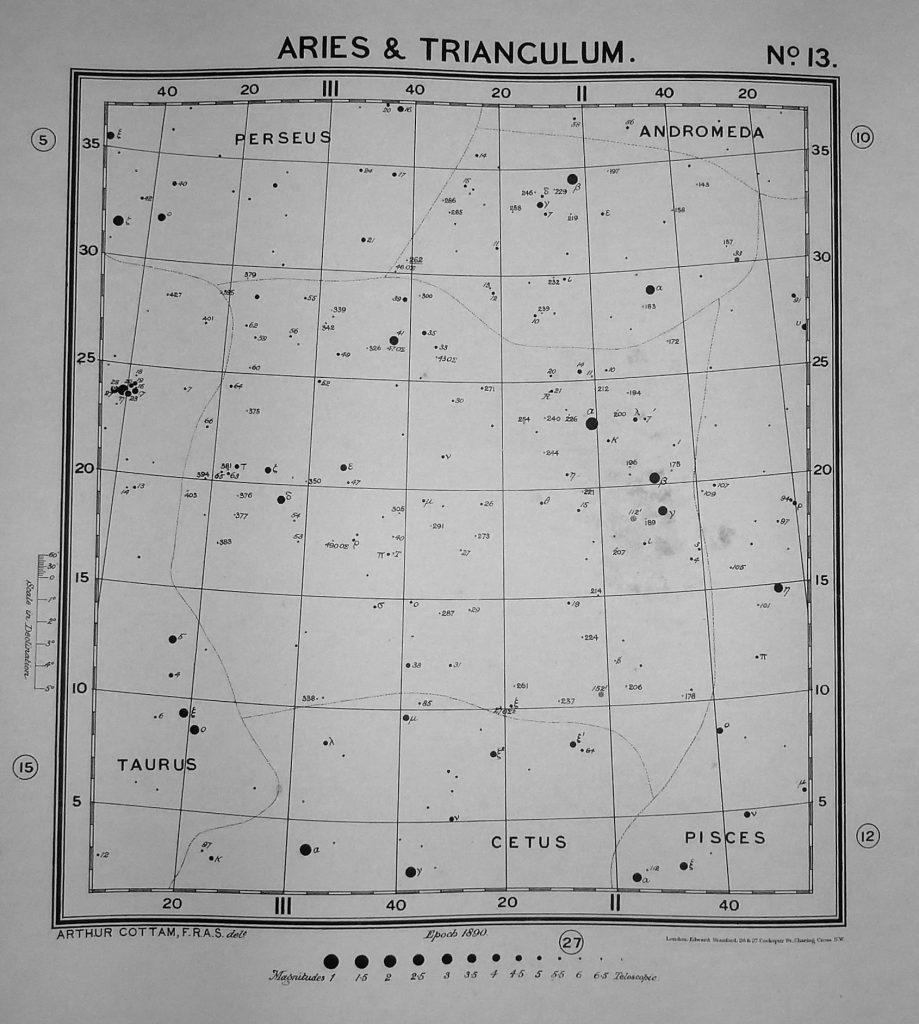

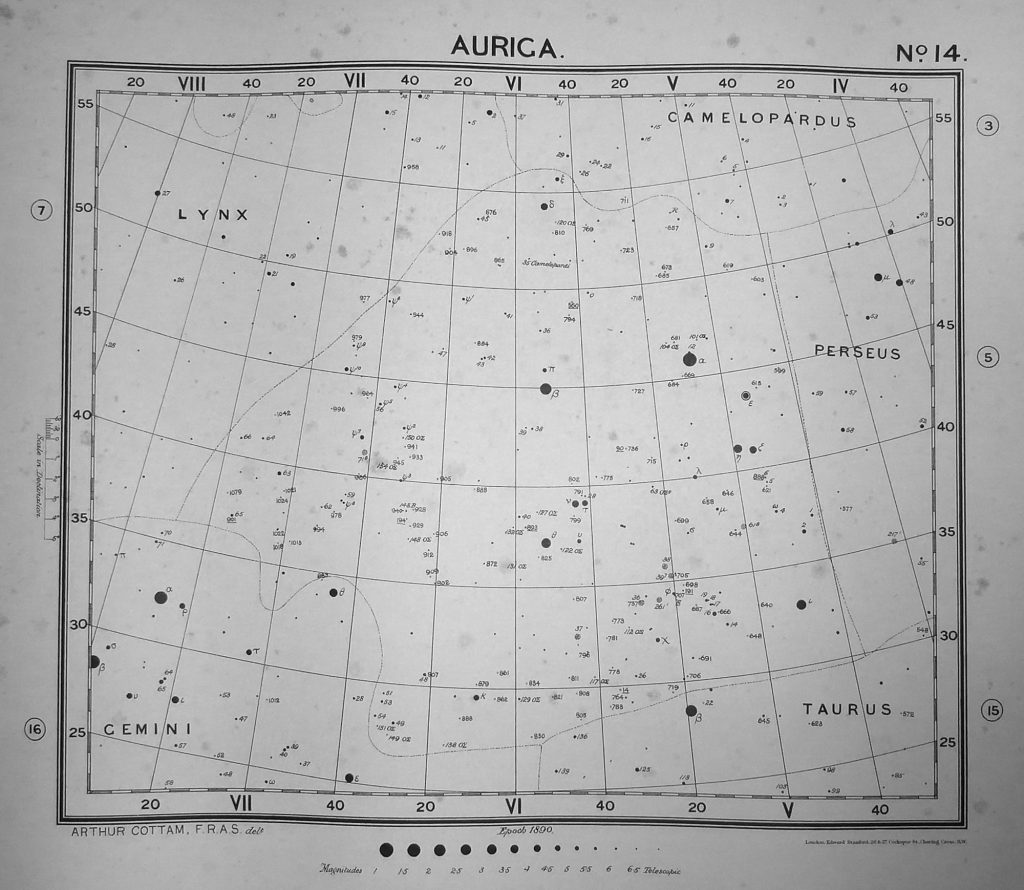

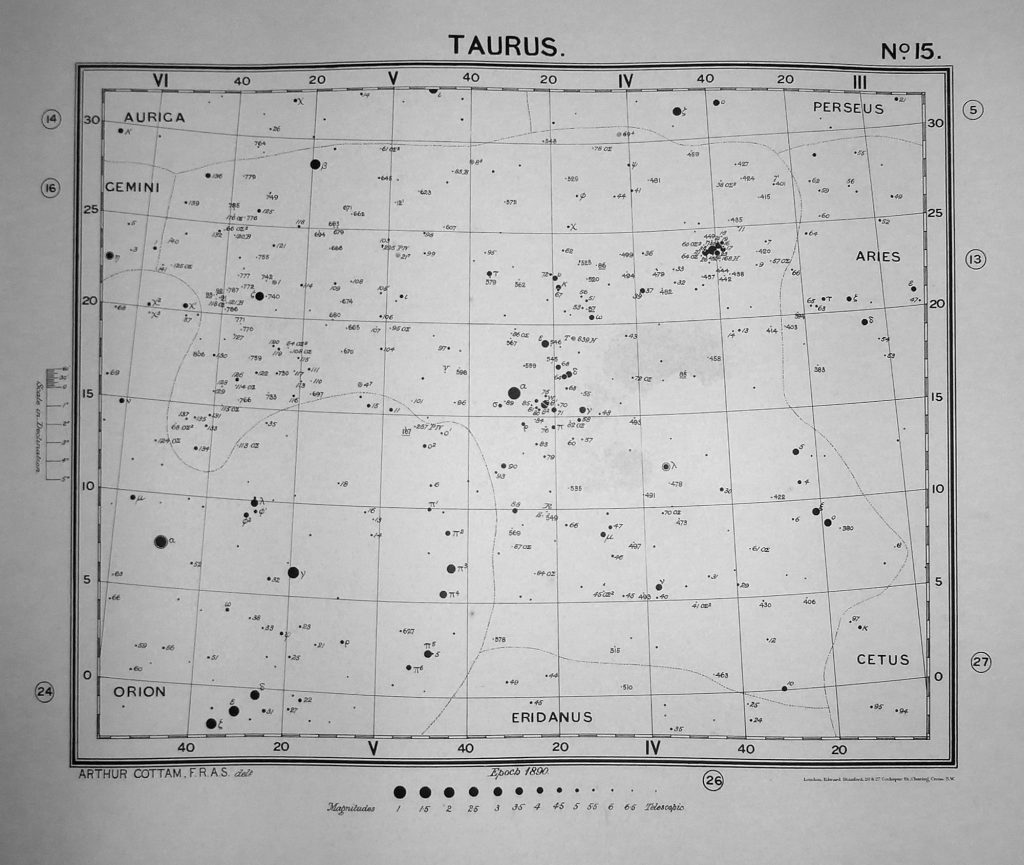

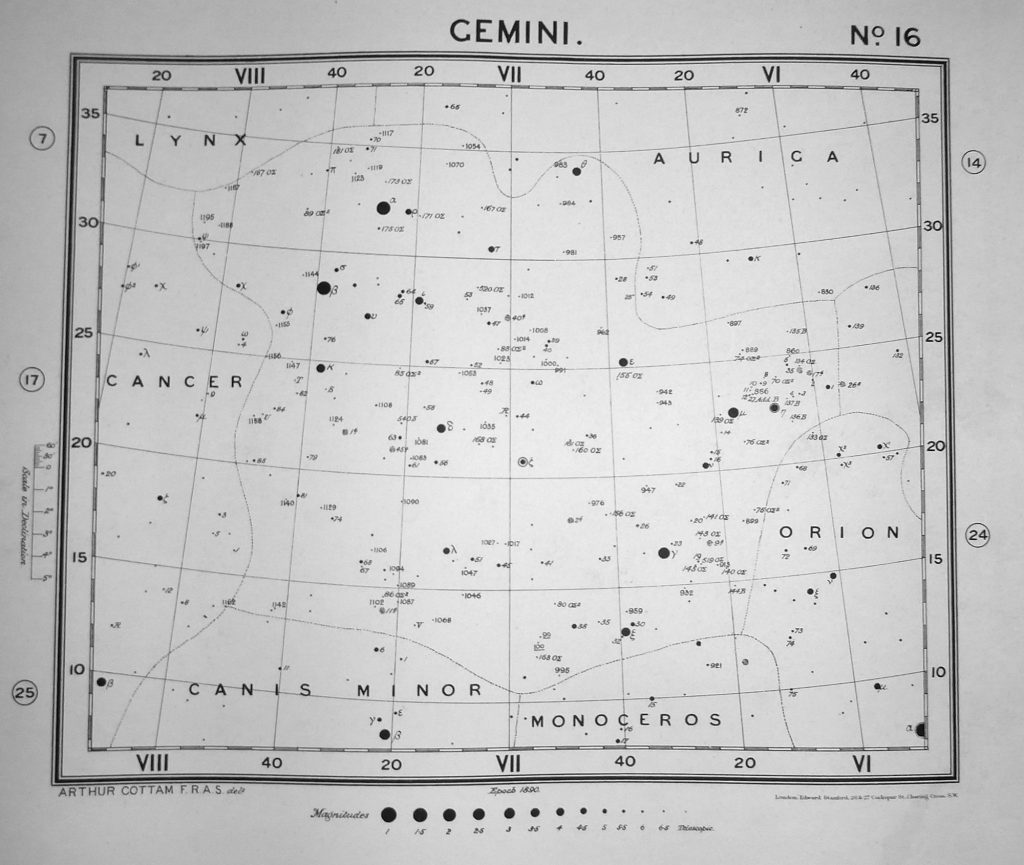

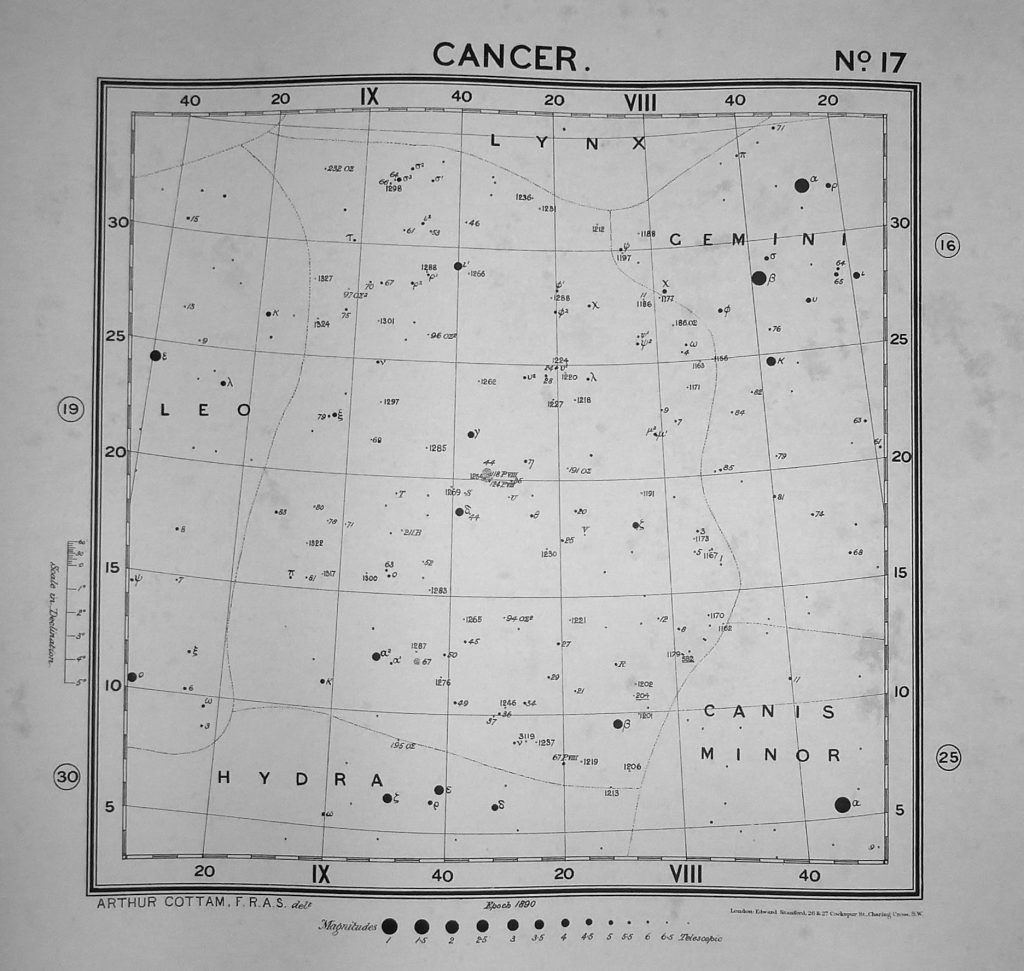

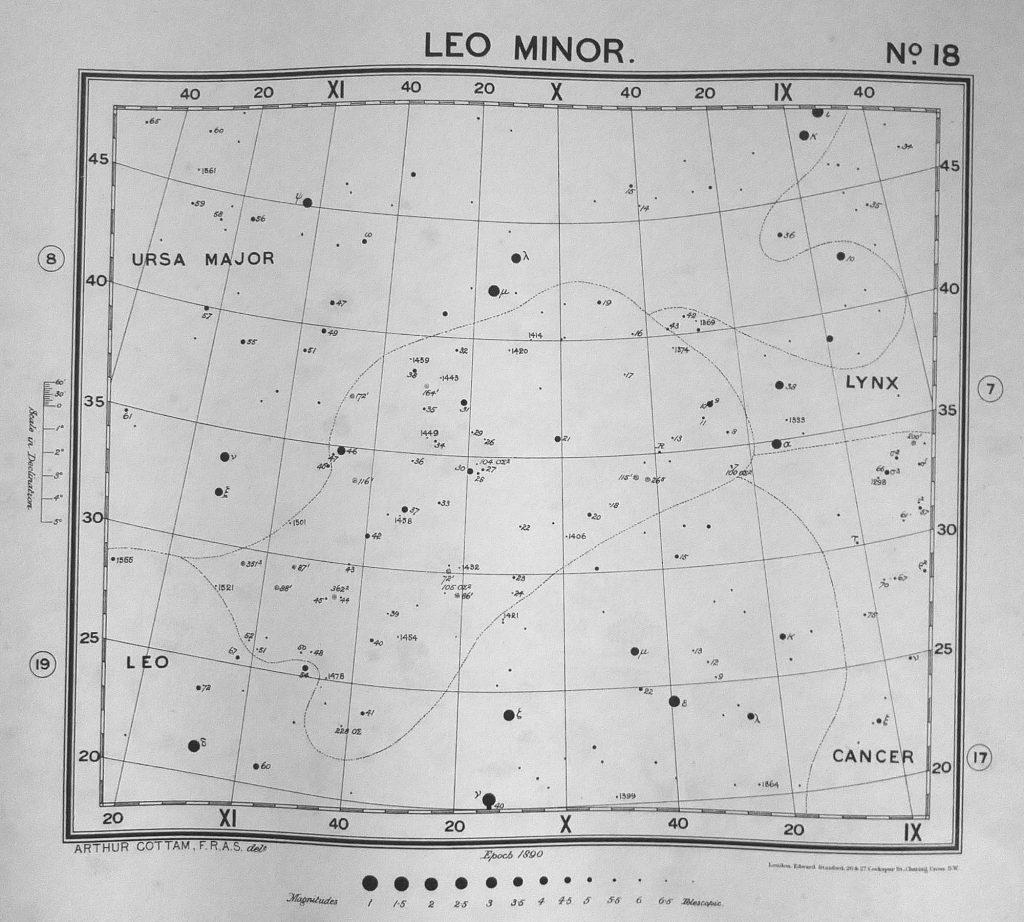

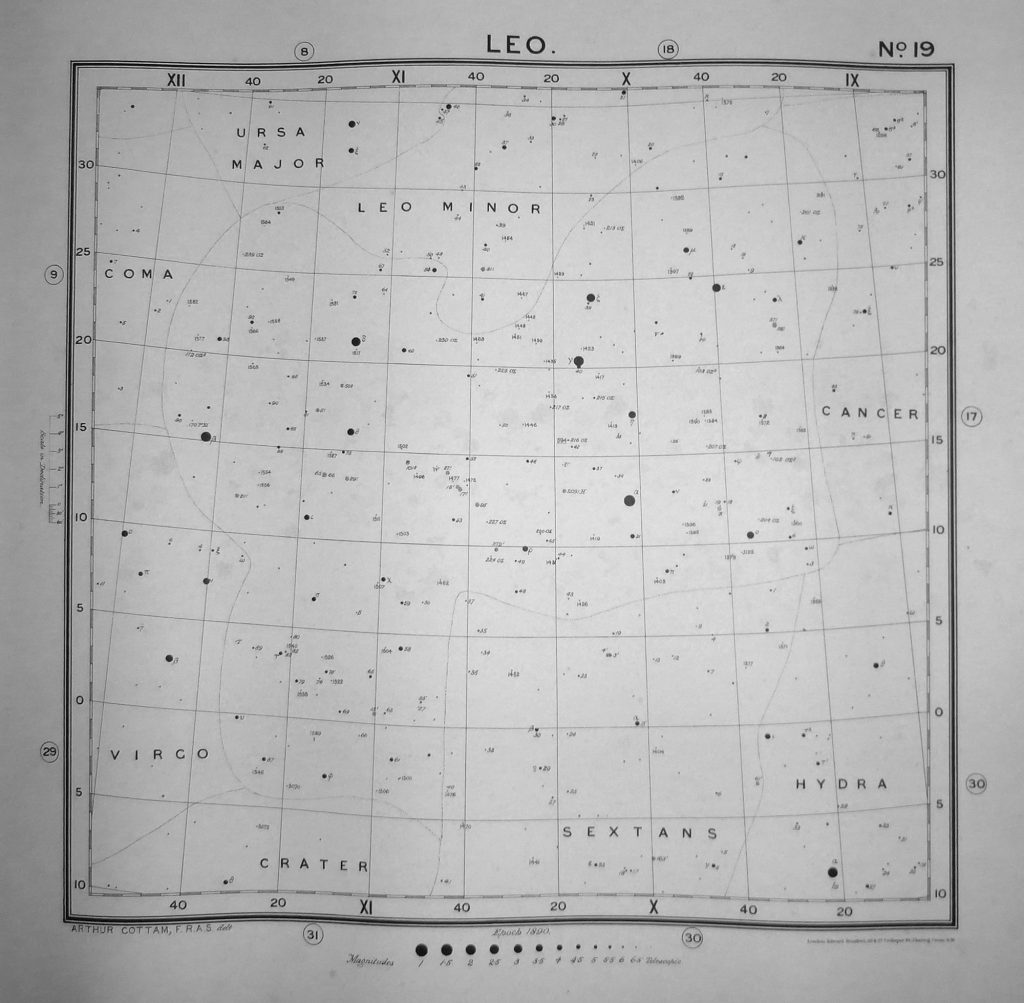

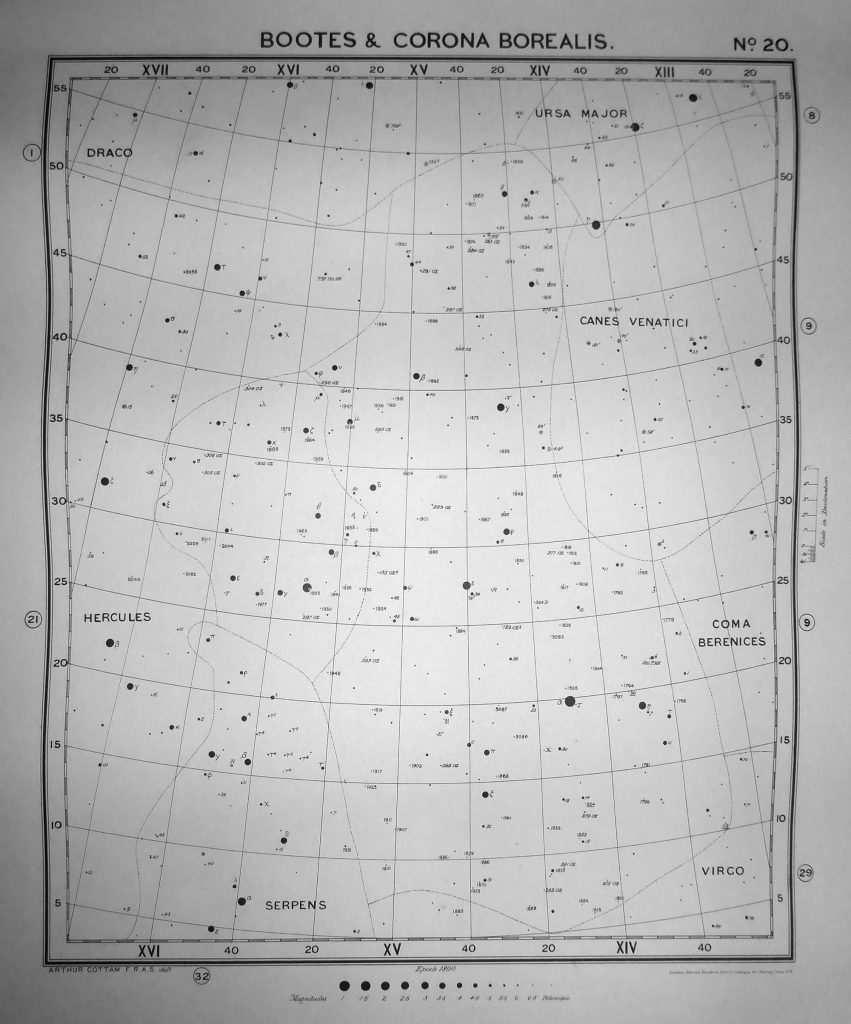

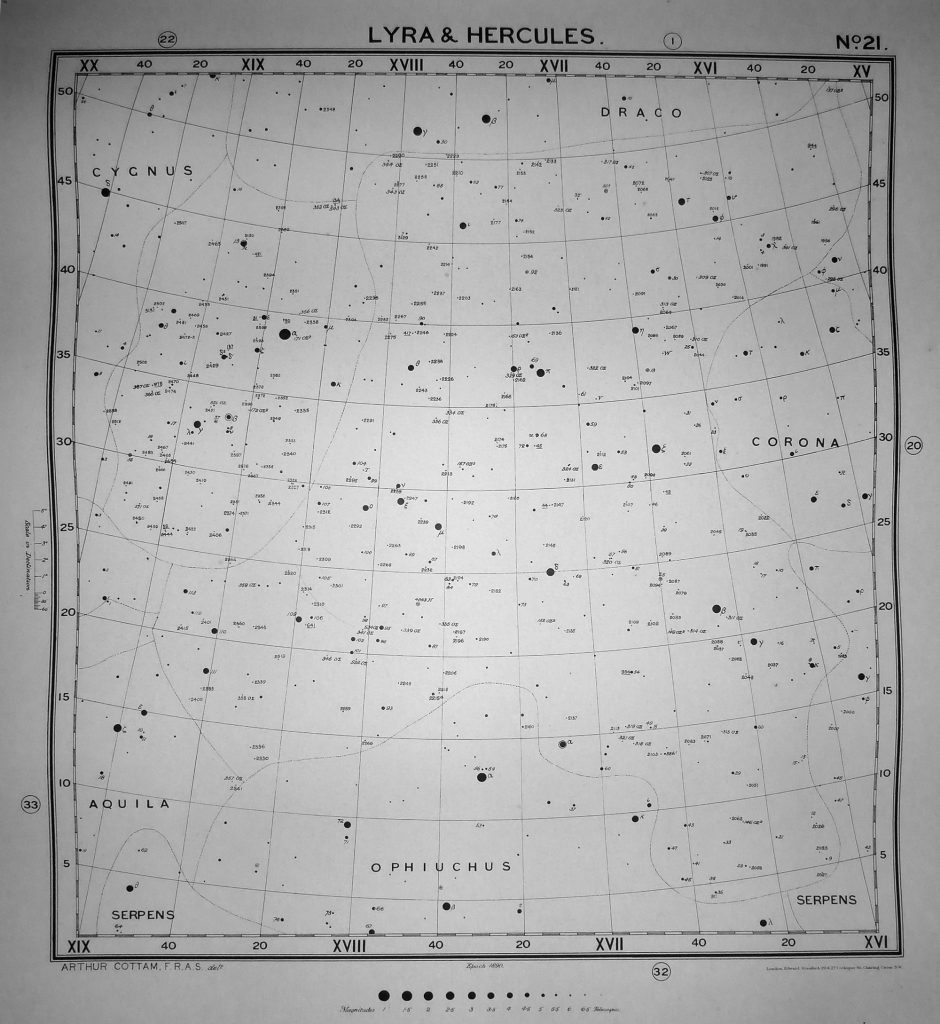

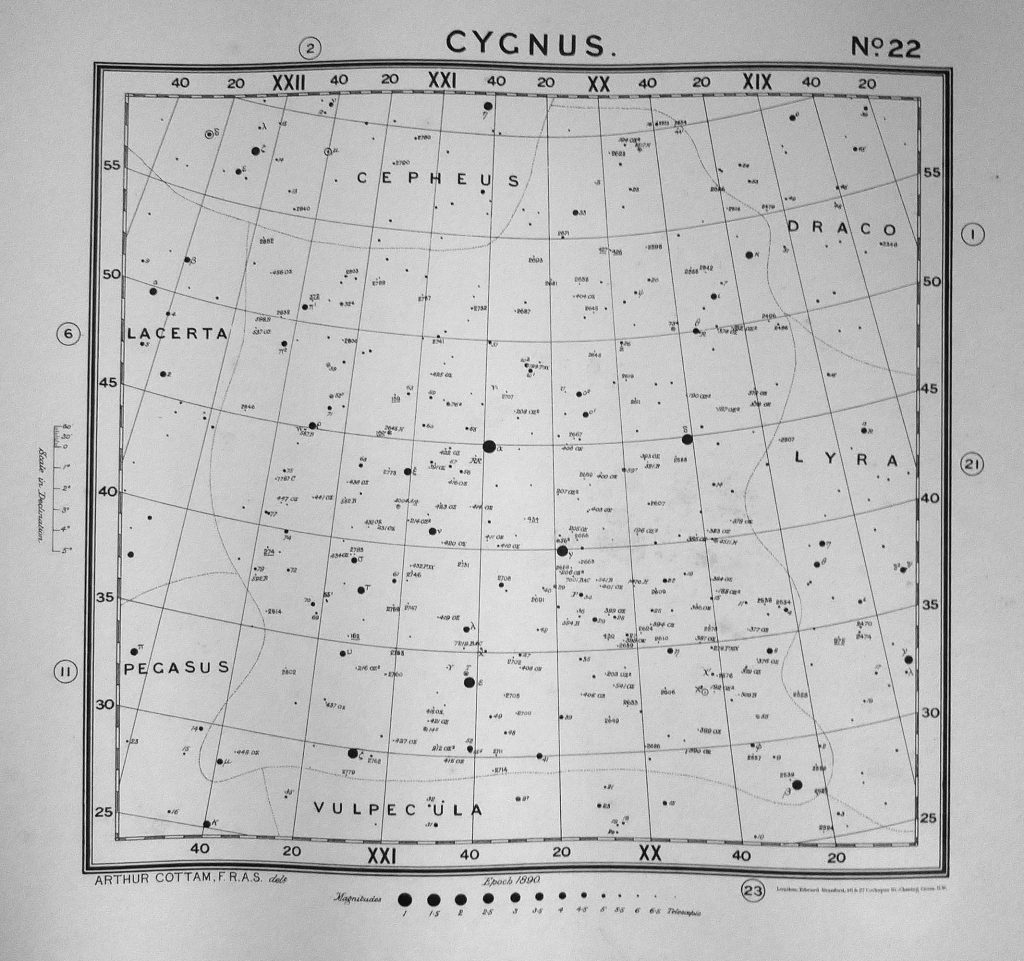

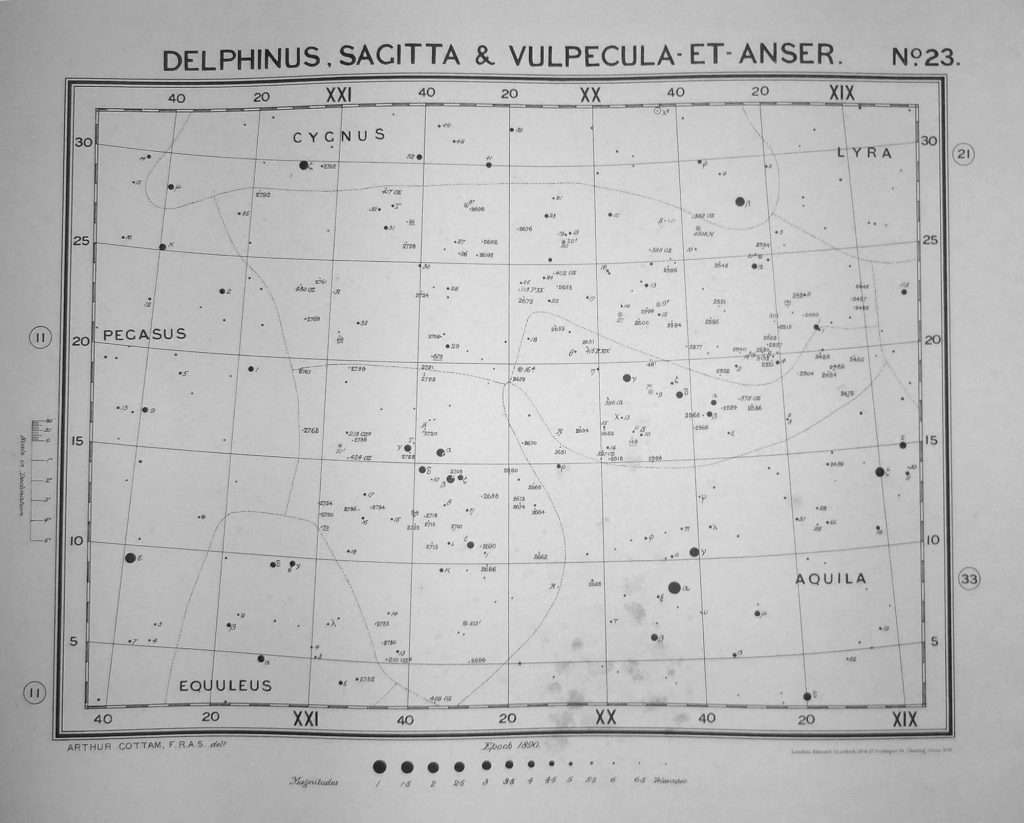

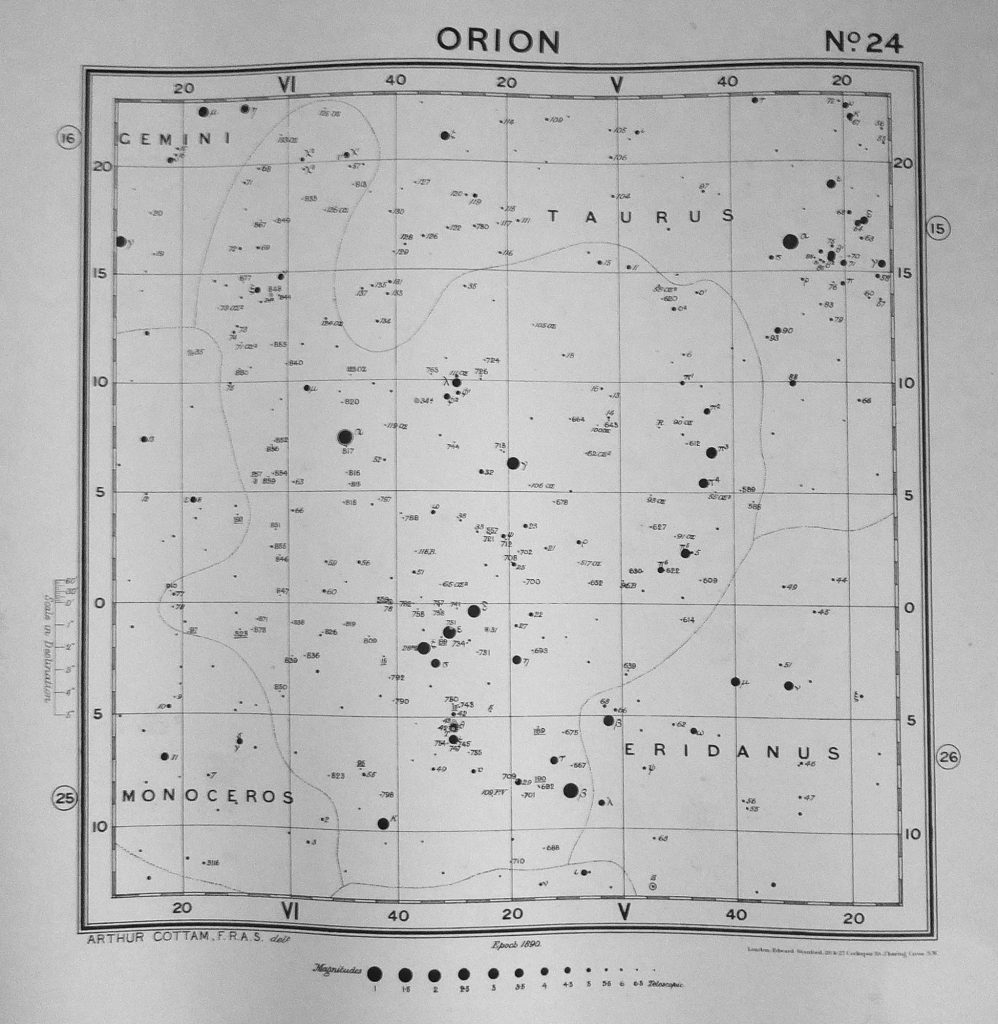

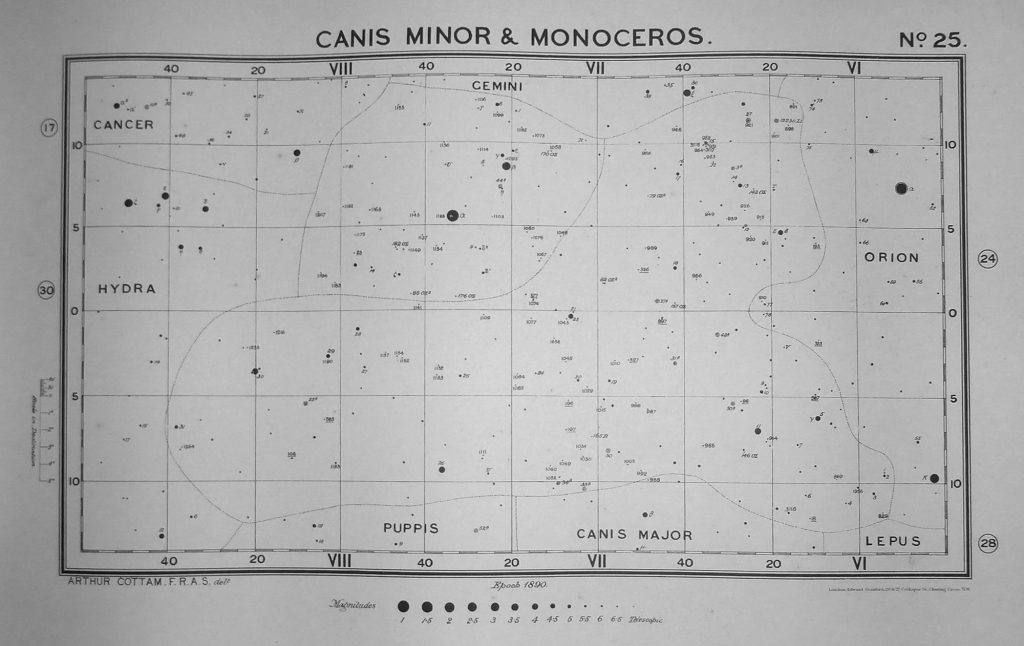

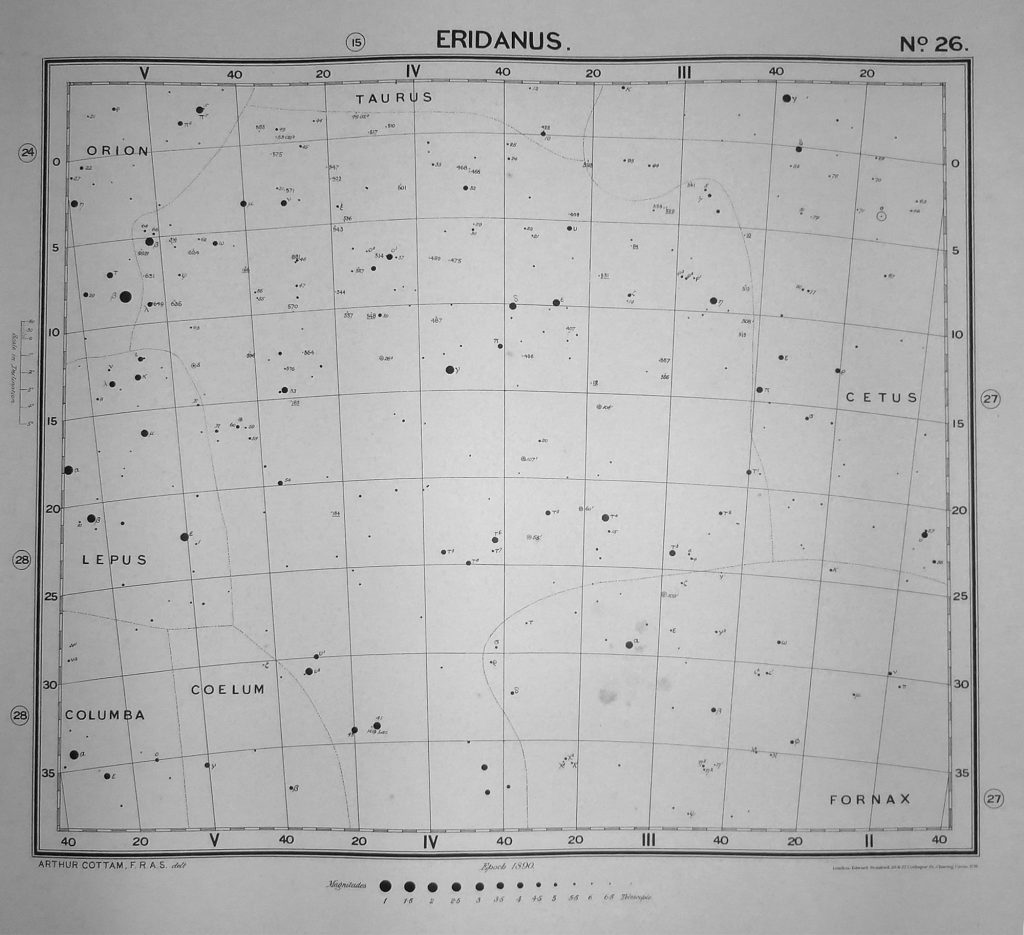

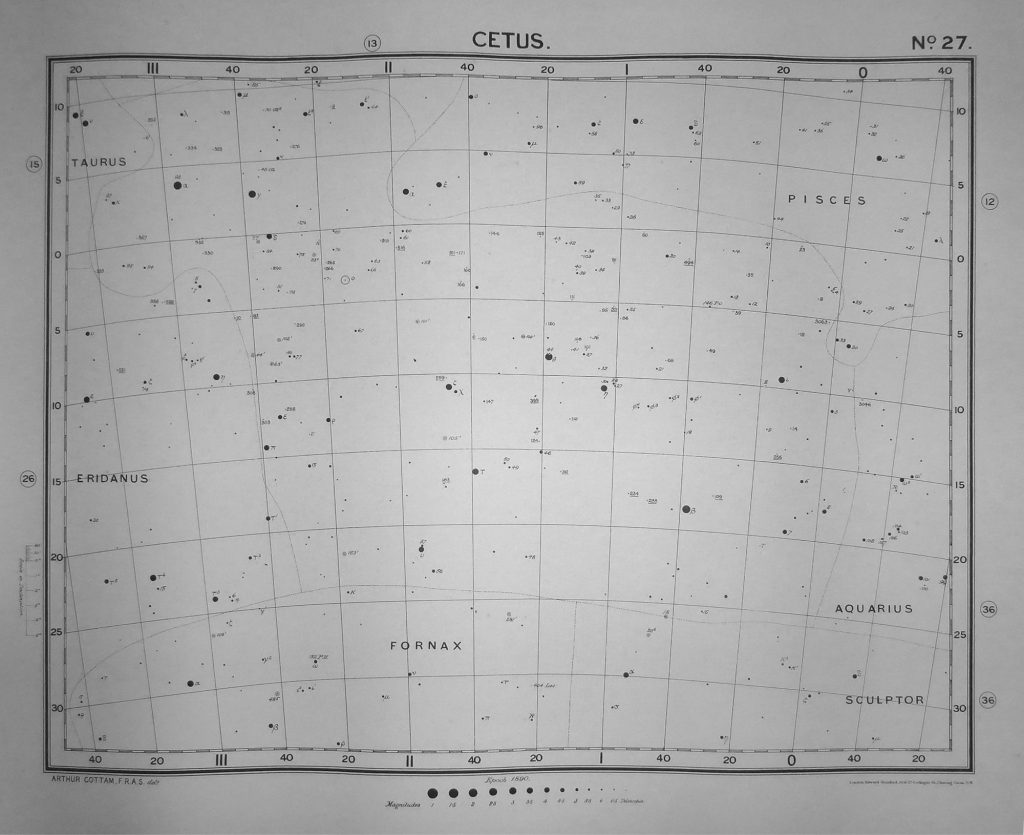

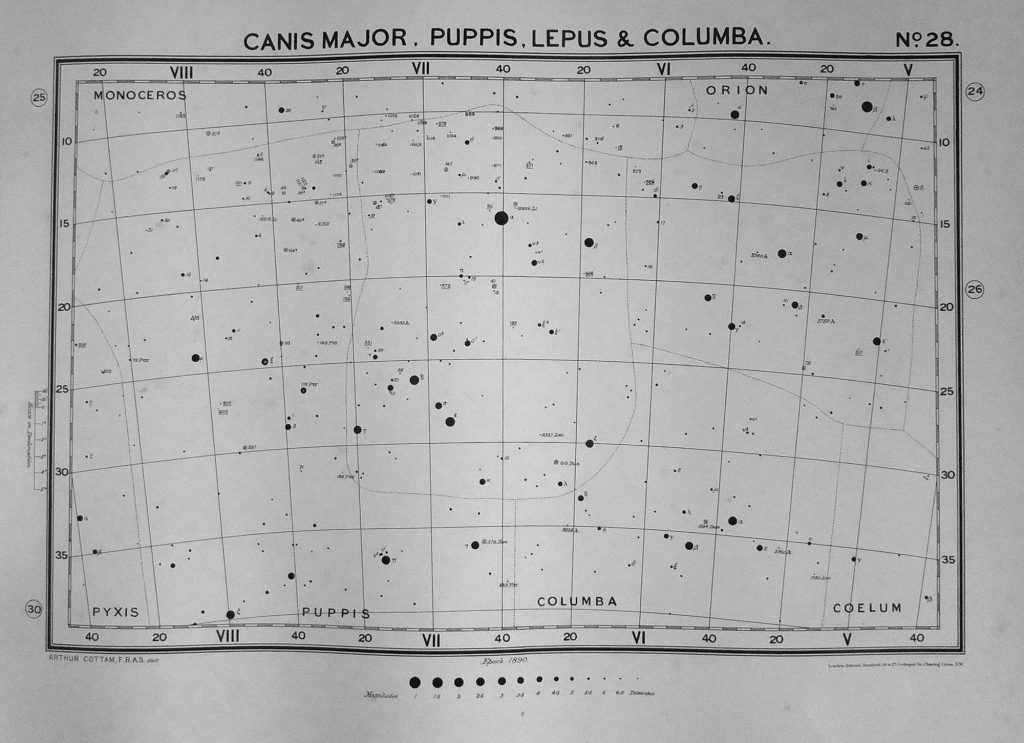

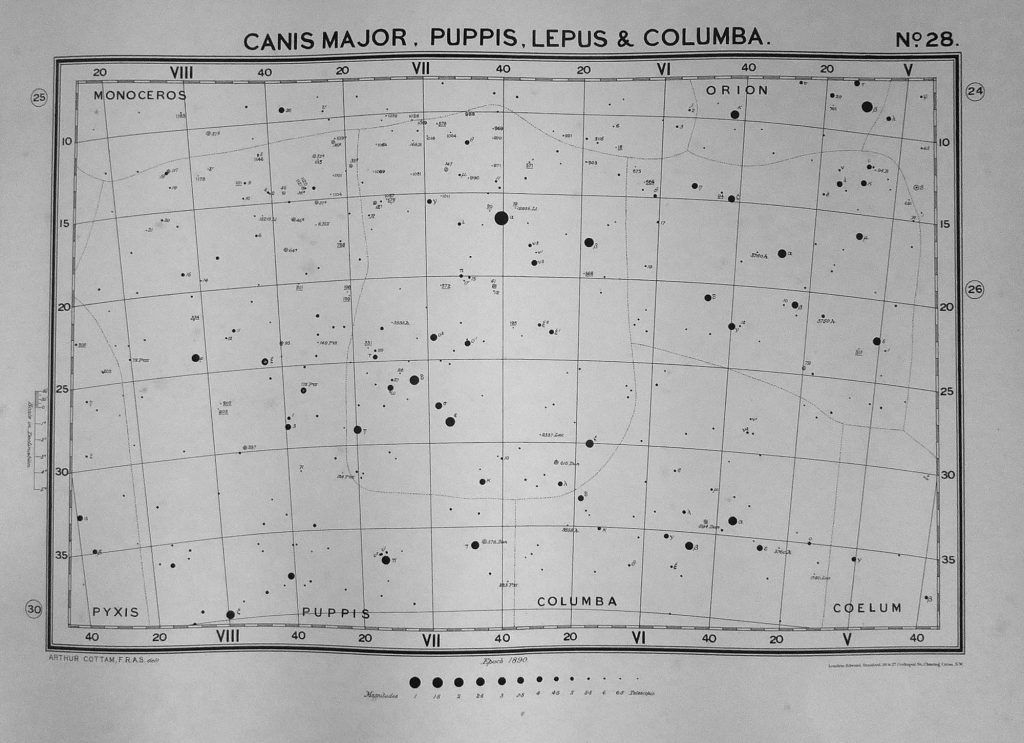

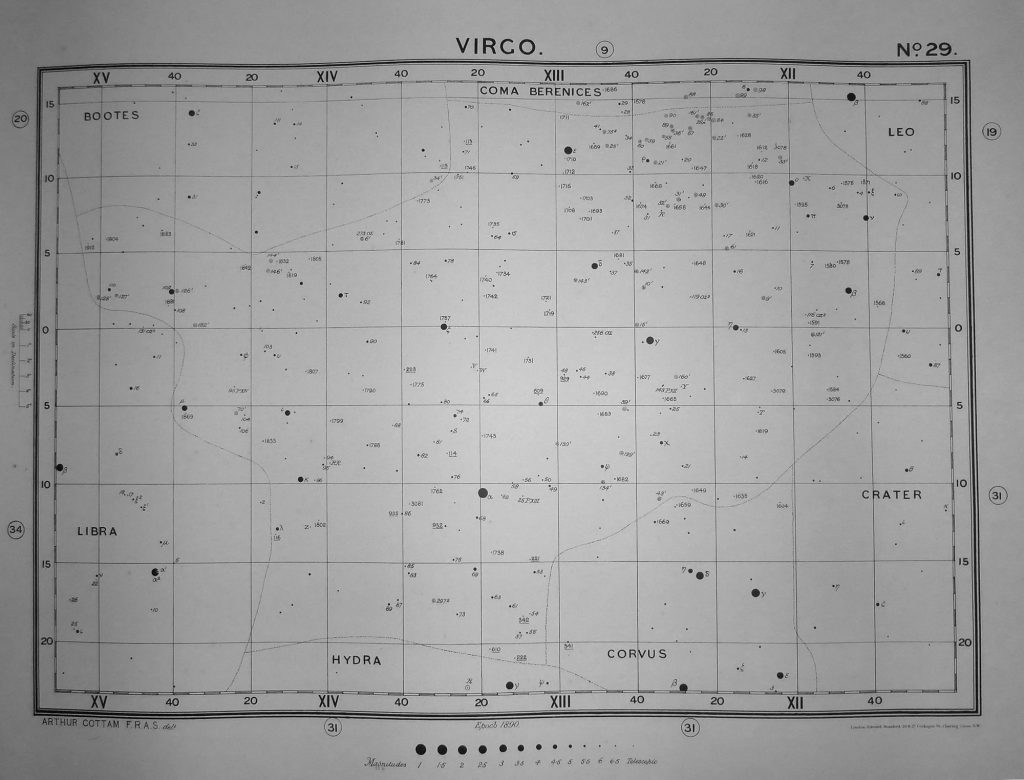

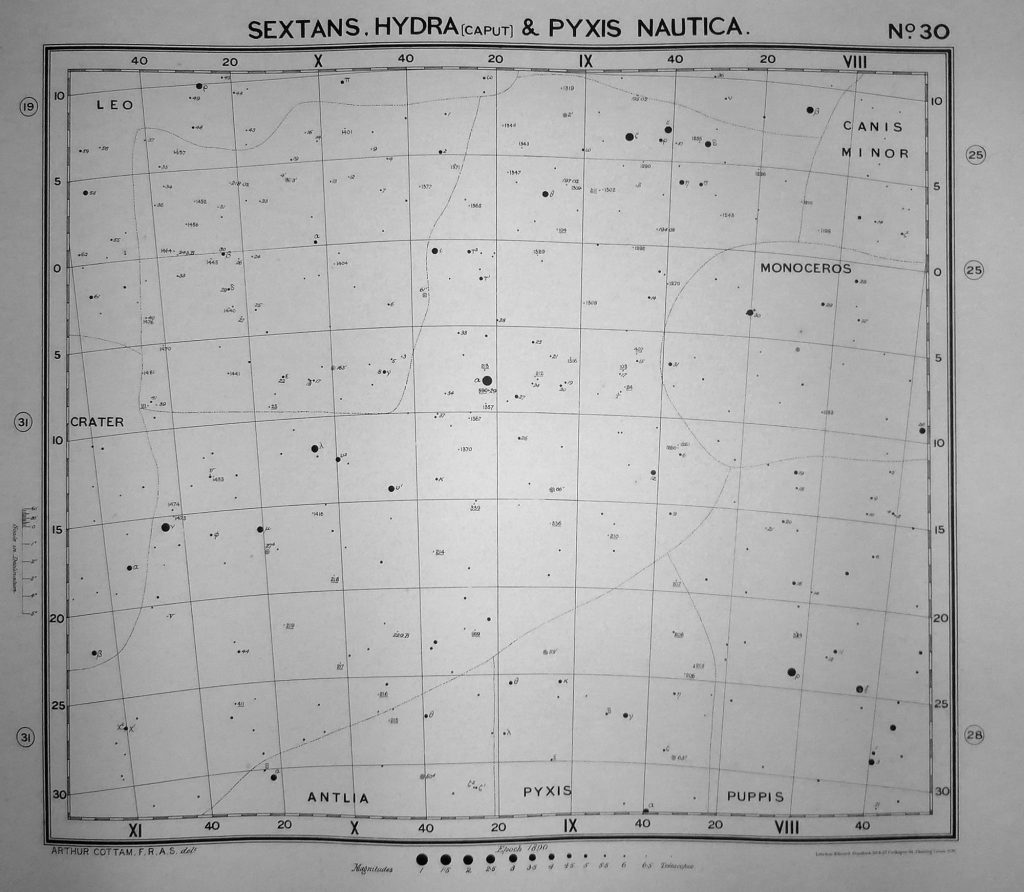

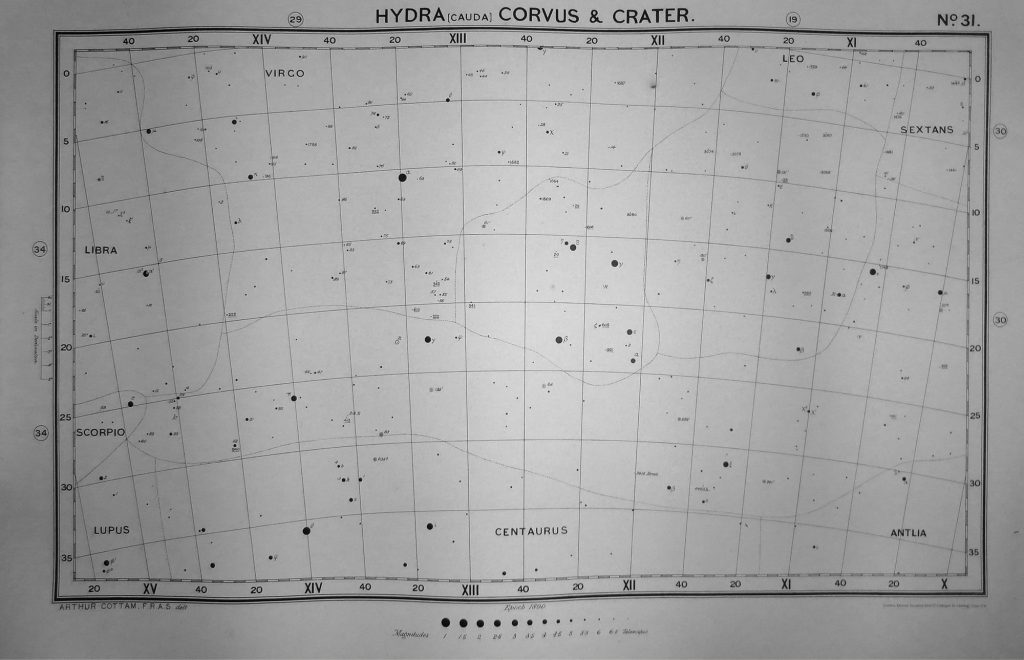

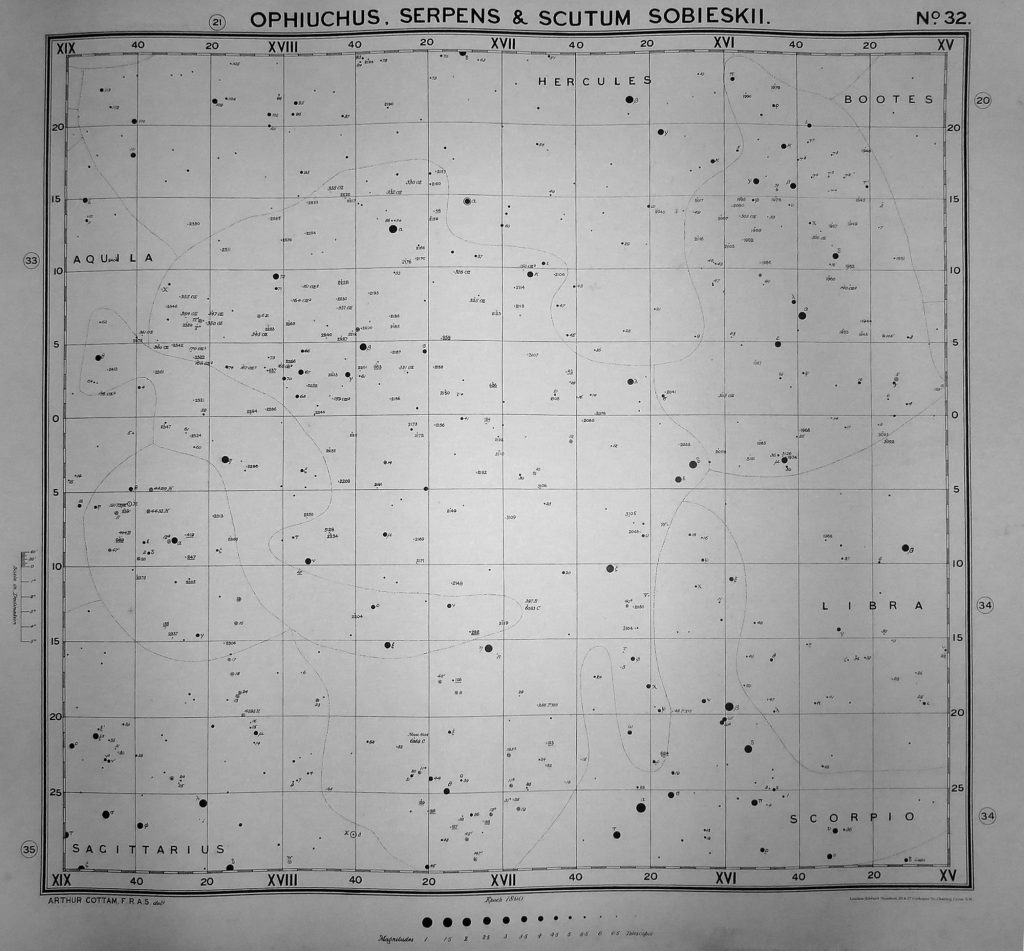

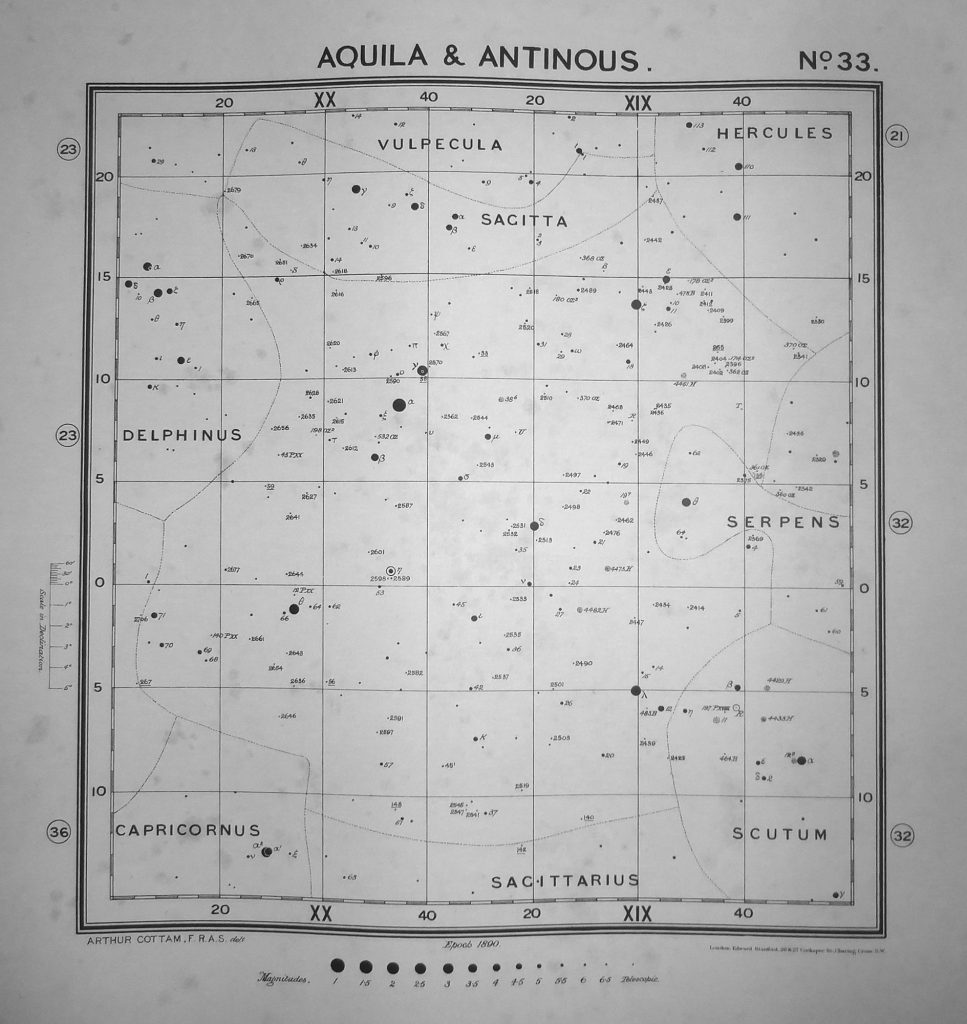

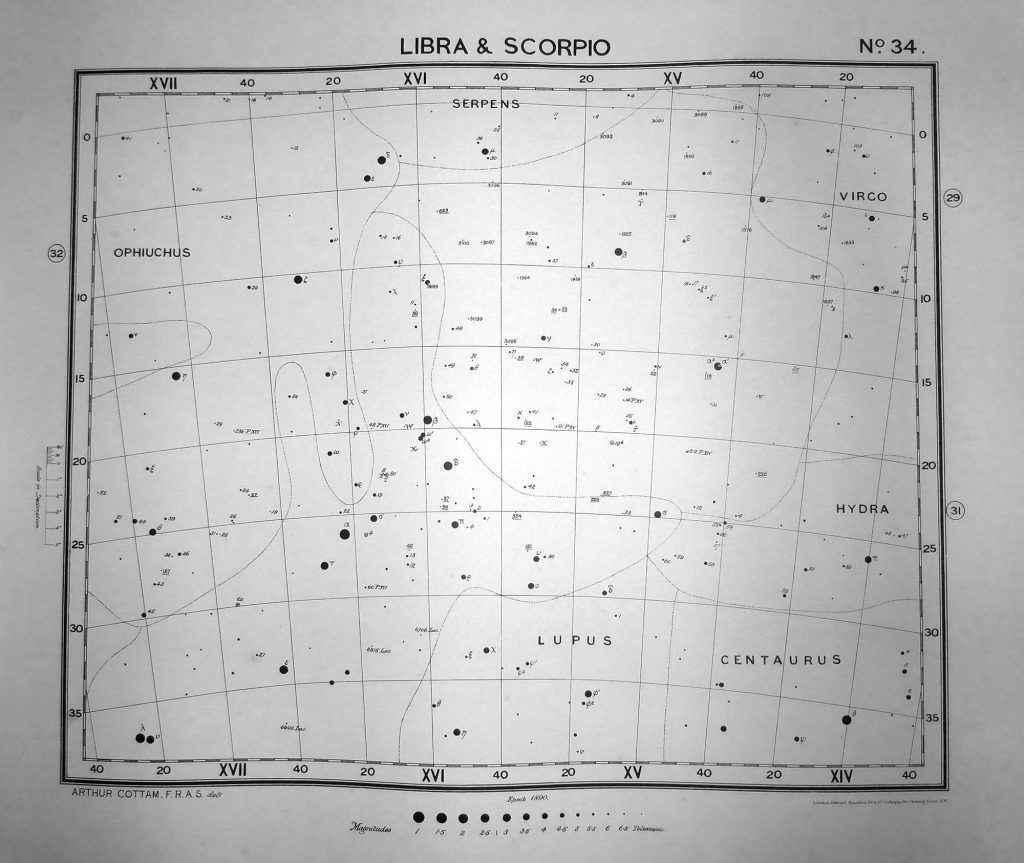

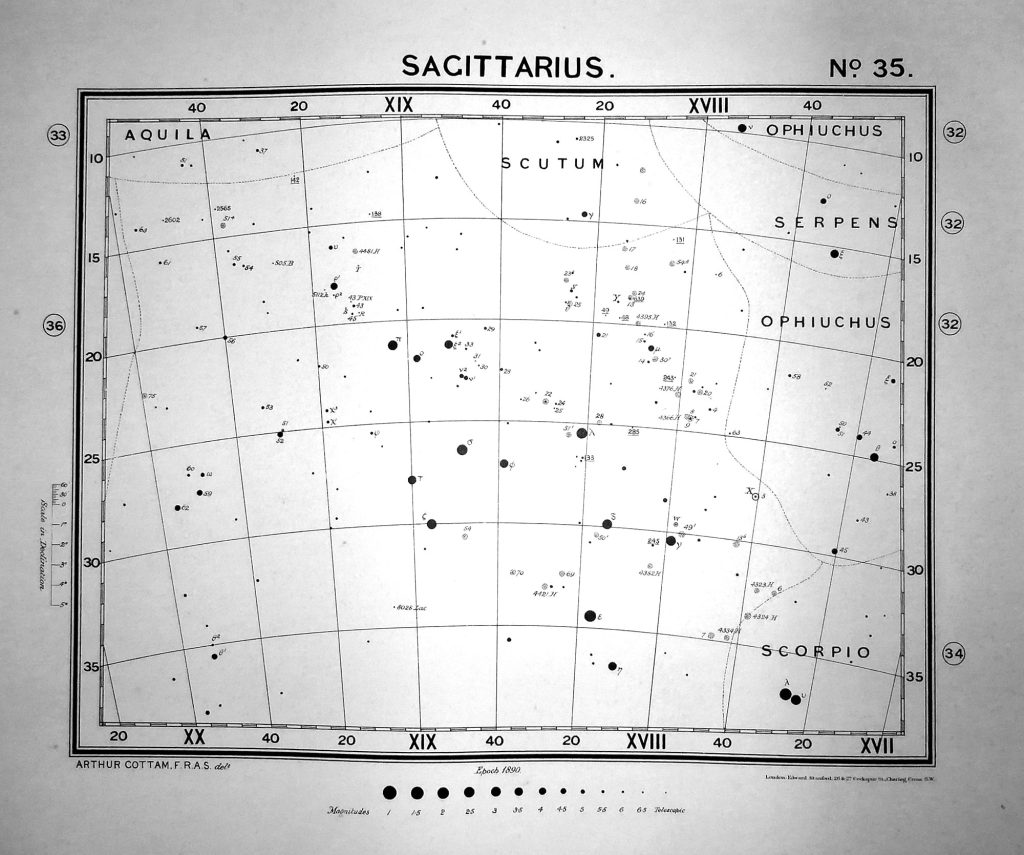

Arthur’s specialty was star charting and he was both knowledgeable and meticulous. ‘Charts of the Constellations from the North Pole to Between 35 and 40 Degrees of the South Declination. A Folio of 36 Maps.’ was published in 1889 and is reproduced below. It was more than just a collection of beautifully drawn charts as Arthur added many original features, made possible by diligent observations with a good telescope.

By 1890 the RAS was focusing more on the work of professional astronomers and so the British Astronomical Association (BAA) was formed to support the amateurs. Arthur was one of the original joint secretaries in the section focusing on observations. He was also very interested in the Jupiter section and was its director between 1898 and 1902.

Arthur was an early member of the Queckett Microscopical Club, which was formed in 1865. It is a learned society including both amateurs and professionals that aims to promote microscopy. Arthur joined in 1869 and served on the Club committee from 1876 to 1878. One of the aims of members was to produce slides that would be of interest to the others. Arthur was an authority on fossil diatomaceae and an expert on making microscopical slides. His slides are still collectors’ items, especially those of diatoms. He also made slides of plants, fungi and insects. Each slide has Arthur’s red ink on white AC monogram, which he registered as a trademark.

Arthur was one of the founders of the Watford Natural History Society (later the Hertfordshire Natural History Society) in 1875 and was its first treasurer. He served on its council, delivered lectures on slide preparation and diatoms and helped organise field meetings. None of the other members matched Arthur’s skill and interest in microscopy, but Arthur also enjoyed collecting moths and butterflies and studying insects, which were interests shared by many.

In 1905 Arthur and Mary moved to Furze Bank, Durleigh Road, Bridgwater, to be closer to Basil. Arthur died on 23 November 1911 at Furze Bank, aged 75.

Charts of the Constellations from the North Pole to Between 35 and 40 Degrees of the South Declination

Preface

WHEN, in 1881, the fourth edition of the Rev, T. W. Webb’s Celestial Charts for Common Telescopes was published, I could obtain no maps upon which a considerable number of the stars included in his lists could be found and identified. Proctor’s smaller Atlas was prepared specially as a companion to the third edition of that book, but the last edition included 1080 additional stars from F. G. W. Struve’s Dorpat Catalogue of double and multiple stars, besides a number from the catalogues of S. W. Burnham.

In the same year was published the Celestial Cycle, the re-issue by Mr. Chambers of Admiral Smyth’s Bedford Catalogue with numerous additions.

These charts were projected as companions to those two books, but their scope has since been considerably enlarged. They now show the whole of the stars (2775 in number) contained in the Earl of Crawford’s (Dun Echt) Summary of Struve’s Dorpat Catalogue; the whole of the stars (650) contained in Otto Struve’s revised Pulkova Catalogues of double and multiple stars, and a large selection from the catalogues of Burnham—the whole of the stars contained in the first four catalogues (which were all discovered with a 6-inch refractor), and a selection from the later catalogues-360 stars in all.

Mr. Webb, in a footnote on page 154 of the first edition of his book, published in 1859, suggested the lines upon which he considered that star maps should be laid down. He says, “An improved work, on the plan of Jamieson’s Celestial Atlas (1822), is much wanted, every Constellation of importance being separately represented;” and he goes on to quote a remark of Sir John Herschel, that in every map he had ever used, “the leading stars in the map are not those which catch the eye by their brightness in the heavens.”

I have endeavoured to meet these requirements. Each constellation (with the exception of “Hydra,” on account of its great length) is shown complete in a single chart. Some charts include two or more constellations, and in every case the naked-eye stars in the surrounding Asterisms are filled in up to the borders. The stars are shown by circular discs on a bold scale, and I think the criticism of Sir John Herschel, quoted above, will be held not to apply to these maps.

Scale.

The scale is one-third of an inch to a degree of a great circle. The original maps were drawn by me to a still larger scale—half an inch to a degree—and they have been reproduced by photolithography, the necessary reduction being made in the process of photographing them.

Projection.

The projection is conical, or, in such constellations as extend some distance both N. and S. of the Celestial Equator. These projections have two advantages. First, for charts each of which includes only a small portion of the heavens, there is very little distortion; practically none that is appreciable by the eye: and, secondly, all the meridians of Right Ascension being straight lines, and all the parallels of Declination being circles or lines that are everywhere precisely the same distance apart, it is an easy matter to lay down correctly the positions of any additional objects that it may be desired to show.

With this object in view, the charts are printed upon drawing paper, so that corrections and additions can be neatly made to them.

The divisions in the upper and lower borders of each chart include an interval of four minutes of time in Right Ascension. If a pencil line be ruled through the ends of corresponding divisions in the two borders, the space so enclosed will everywhere represent the same interval of four minutes. In any part where a fresh object is to be laid down, it is an easy matter to further divide this space into four equal parts by the eye, and again to lay down the centre of the object to the nearest tenth part of one of these sub-divisions.

There is a, scale in Declination in the margin of each chart ; but I recommend the use of an engine-divided scale for measuring positions in Declination. Mr. W. F. Stanley, of Great Turnstile, Holborn, London, makes a small boxwood scale, six inches long, specially for use with these charts. It is divided alike on both edges to thirds of an inch, each of which is again divided into twelve parts. These larger and smaller divisions represent one degree and five minutes of arc respectively. By these means objects can be readily laid down to the nearest tenth of a minute (six seconds) of time in Right Ascension ; and.to the nearest minute of arc in Declination.

Constellation Boundaries.

Heis’s Atlas Colestis has been used as the basis of these charts. But his boundaries have not in all cases been closely followed, when it seemed advisable to include some of Flamsteed’s stars which he had omitted. I have not attempted to lay down a boundary to the little modern constellation “Taurus Poniatowskii,” but all the objects given by Webb as being in that constellation will be found in Chart No. 32, on the borders of Ophiuchus, Hercules, and Aquila,

Star Magnitudes

These are shown to half magnitudes, Any smaller division was not practicable, and even now the sizes of the discs are sufficiently confusing.

The subject of star magnitudes is only now being worked out upon a definite system. The photometric measures made within the last few years, at Oxford by Professor Pritchard, and at Harvard College (U.S.A.) by Professor Pickering, have established something like a settled scale. By these measures the stars have been divided into tenths of each magnitude.

Heis gives two intermediate between the whole magnitudes, one-third and two-thirds. These are both shown on my charts as a half magnitude

South of to of North Decliniation, Dr, Gould’s Uranometria Argentina has been used to check and supplement Heis; and the Harvard photometric measures have been carefully compared with Heis’s list, and his magnitudes have been altered where it appeared necessary to do so. About 290 stars included in the Harvard Photometry as of 6’5 magnitude, or brighter, but which are omitted by Heis, or rated lower by Gould, have been inserted in the charts. It is hoped, therefore, that no stars visible to the naked eye have been omitted.

A considerable number of Flamsteed’s stars, mostly less than 6’5 magnitude, are omitted by Heis, and the greater part of these I have shown upon these maps.

Variable starts in which the maximum brilliancy exceeds the fifth magnitude are shown by a disc surrounded by a circle, which represent the minimum brightness respectively. This plan is impracticable with starts that are less than a fifth magnitude at their maximum.

No attempt has been made to show the Milky Way. It would only have confused the maps, without, in my opinion, serving any useful purpose.

Epoch.

The epoch of these charts is 1890. I did not anticipate when I commenced them, several years ago, that the work I was undertaking would prove so troublesome as I have found it to be; and I hoped to get them published a few years before the epoch chosen. But they will hold good, without serious errors, for twelve or fifteen years to come.

Lettering.

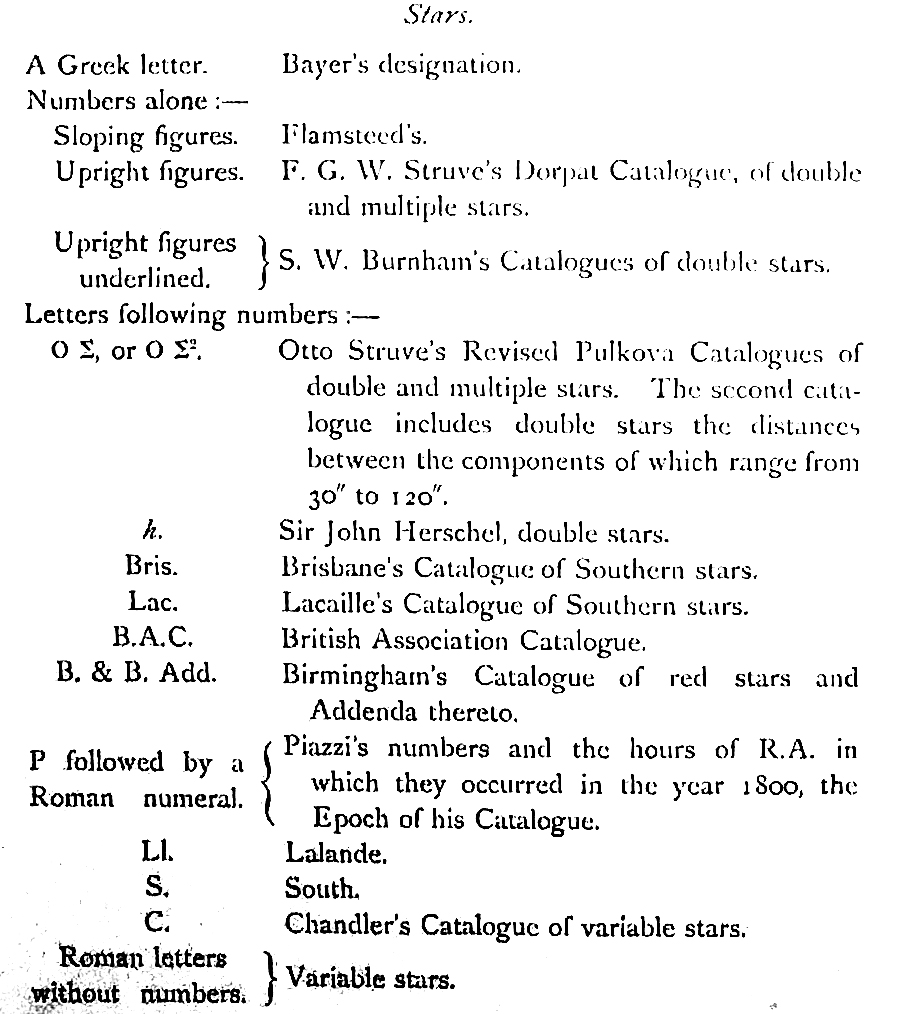

The system I have adopted in lettering these charts has been to give precedence to Bayer’s Greek letters, and after those to Flamsteed’s numbers. Any naked-eye stars distinguished neither by a Greek letter nor a Flamsteed number are not lettered or numbered at all, unless they are of some telescopic interest, i.e. double, variable, or coloured.

In the case of double and multiple stars, other than those already distinguished by a Greek letter or by one of Flamsteed’s numbers, the preference has been given to F. G. W. Struve’s numbers, if a star has two or more synonyms. Variable stars, where not at once distinguishable by a ring and disc, are as a rule shown by a Roman letter, generally a capital, and usually between R and the end of the alphabet.

In two constellations, Cygnus and Virgo, these letters have all been used up, and will now be repeated doubled, e.g. RR, &c.

Two new catalogues of variable stars have been published recently. J. E. Gore’s Revised Catalogue (in the Proceedings of Me Royal Irish Academy, 3rd Series, vol. i. No. i, December 1888). In this catalogue, a number of the recently-discovered variables have been left undistinguished by letters for the present. The other catalogue is by S. C. Chandler (published in the American Astronomical Journal, Nos. 179, 180, 1888). In this catalogue all the new variables are lettered, and I have inserted the letters proposed by Chandler. If any of these should ultimately not be adopted (which is very unlikely), the maps can be altered by erasing them and inserting others.

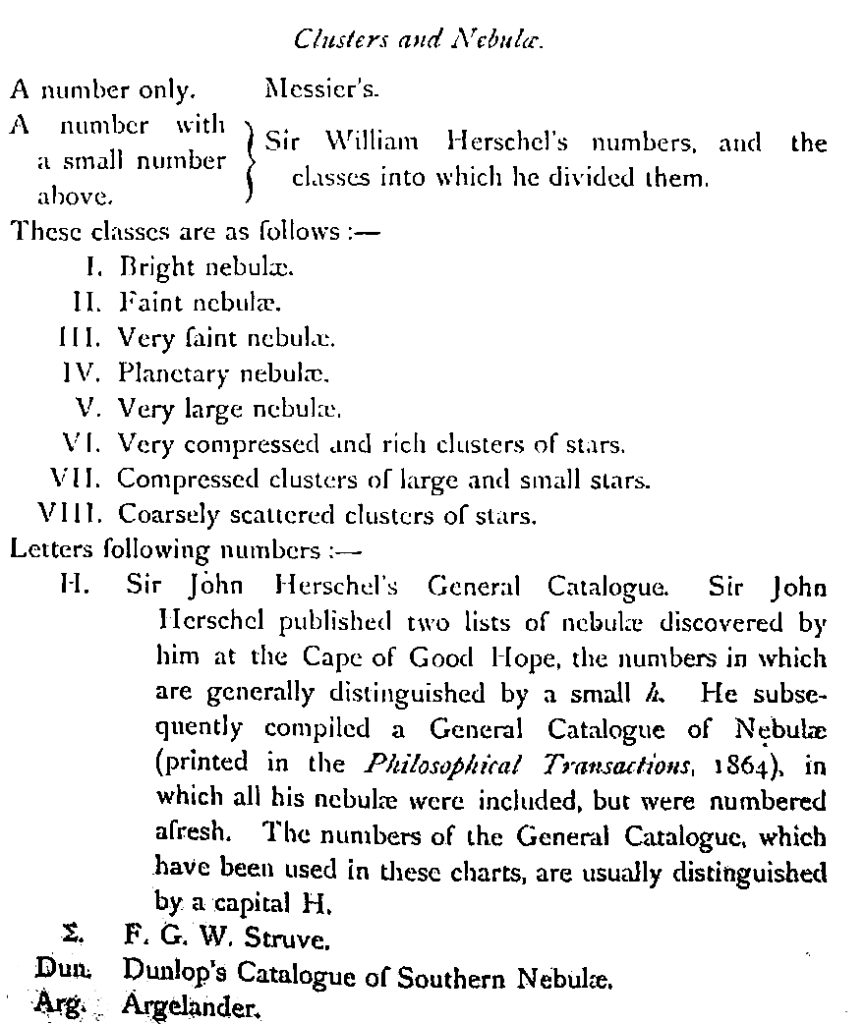

The following is a full key to the lettering of the Charts :—

I am indebted to the Earl of Crawford and Balcarres for the gift of a copy of his Dun Echt Summary of F. G. W. Struve’s Dorpat Catalogue of double and multiple stars, and to several friends for advice and assistance in a variety of ways; and I desire to acknowledge my obligations, and to express my thanks to them.

To Mr. E.B. Knobel, Mr. N.E. Green, Mr Herbert Sadler, and the late Mr. C.G. Talmage, I am indebted for the loan of many valuable books, and for suggestions and advice that materially assisted me in carrying out my work with such success as I may have achieved.

And to my cousin, Mr. Kenneth J. Tarrant, for the laborious work of comparing’ and checking the whole of the charts with the lists. This tedious and monotonous work he carried through with most persevering care and to it is due the elimination of a considerable number of errors made in laying down so large a number of objects – errors very difficult to avoid, however carefully such work may be done.

In conclusion, I would express my hope that these charts will be found to be useful in a variety of ways, but especially that they will help the possessors of telescopes mounted without circles, or on alt-azimuth stands, to find, with little or no difficulty, a large number of interesting objects; and that they will do something to extend the knowledge of the wonders and beauties of the Heavens, and to popularise one of the most fascinating – as it is the most ancient, and the noblest—of all the sciences.

ARTHUR COTTAM

Eldercroft, Watford, 1889.