John Creedy, c. 1772-1846

The baptism for John Creedy has not been found yet, but his year of birth was around 1772, according to the age he gave in various documents. The only place of birth shown for him was Enmore, but no likely baptisms have yet found for him in this area. John was illiterate, so the spelling of his surname depended on whoever was writing it down and over time it varied between Greedy and Creedy, with several other spelling variations. During the 1830s, the spelling settled on ‘Creedy’.

The first official record of John was on the 23rd of March 1804, when he married Mary Tamlyn in St Mary’s Church, Bridgwater. John, aged about 32, was a bachelor of that parish, and his wife Mary was a minor, aged about 20. They had to get the written permission of Mary’s mother before they could get married.

Working life in Bridgwater

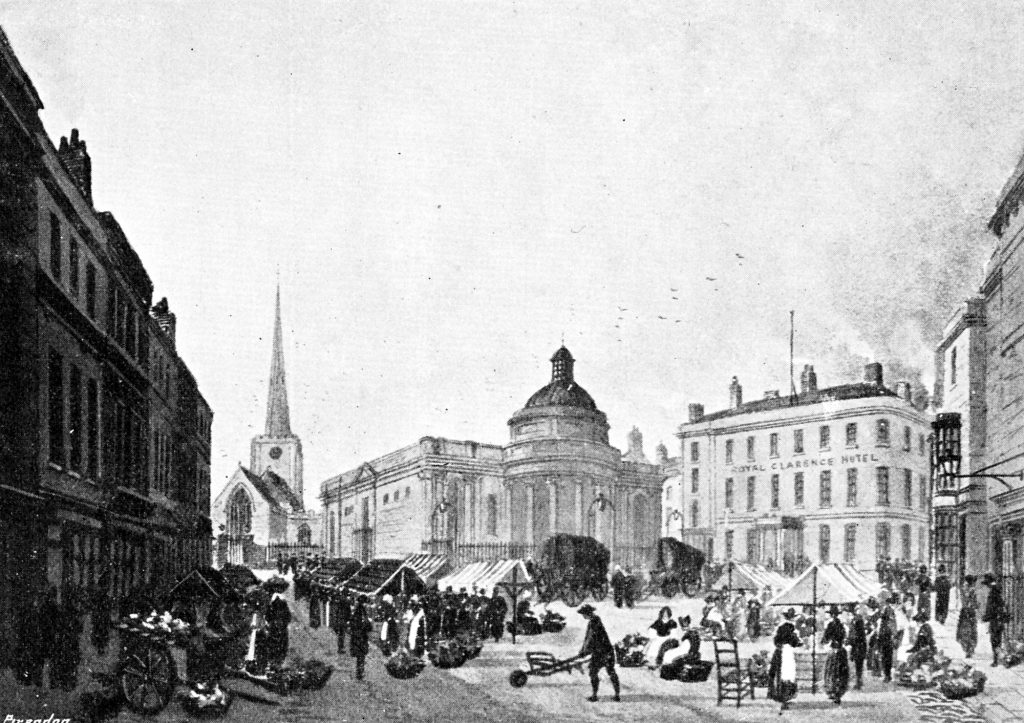

During the early 1800s when John and Mary were setting up their home and starting their family, Bridgwater was a bustling market town and busy port, with a population of around 3,600 people. There were two weekly markets as well as four annual fairs. These fairs and markets would have attracted farmers and traders of all kinds into the town, as well as itinerant street entertainers.

The brick yards, sited close to the river Parrett, exported bricks and tiles by sea to Bristol, Cardiff, Swansea and Irish ports, mainly using small coastal vessels. On their return voyage, these boats would often bring in coal from Wales. Fishing and cargo vessels moored along the quay on the river bank, and at the head of the quay was a fine new cast iron bridge. Several inns were situated in the town centre, catering to the visiting merchants as well as thirsty workers and shoppers, and many more inns and beer houses were to open over the next few decades.

With merchants and traders coming to the port and the markets by road as well as by sea, there was plenty of loading and unloading work for a labourer such as John Creedy, as well as brickyard work. All this activity meant that the town began to attract workers from the villages around. Bridgwater grew rapidly during the next few years, the population increased by a quarter in the decade after 1801, and continued to increase quickly for the next few decades. Construction would have provided more working opportunities, but the rapid growth in population still resulted in cramped housing conditions for the poorer families, and more competition for labouring work.

Hard times

John and Mary had three children between 1804 and 1811, so John had extra mouths to feed. The brick industry was a major employer in Bridgwater, but the yards usually laid off many of their workers during bad weather in the winter. These workers then had to find other labouring jobs to get them through this time. Building and dock work could also decline sharply during the colder months, so many labourers would be turned away without any pay. There was no social security system to help poor families, other than a small amount of parish relief, so it could be extremely hard to pay rent and put food on the table.

Not surprisingly, men with hungry children would have to try to find food where they could. This might involve trying to forage for nuts and berries in hedgerows, but this was unlikely to be sufficient to feed a family and so some might turn to poaching. Documents preserved in the South West Heritage Centre give a surprisingly detailed account of one such incident, involving John Creedy.

In 1811, as well as their three children, John and Mary were also supporting Mary’s sister Elizabeth Tamlyn and her half-brother William Dawe. By the end of 1811, John was being unlawfully creative in his attempts to feed his extended family.

Information of John Gibbs, maltster of Bridgwater 20th of October 1811

The case starts when John Gibbs, a maltster, lodged information on oath with a magistrate. Gibbs alleged that John Creedy had stolen seven empty bags, and so a warrant was issued to search John Creedy’s house.

Examinations of Joseph Durston, constable, Richard Cave, accountant, Thomas Cape, yeoman, John Graham, merchant and John Gibbs, merchant (and maltster), all of Bridgwater, taken on oath 29th of October 1811

The witnesses Richard Cave, Thomas Cape, John Graham and John Gibbs were all relatively wealthy businessmen, compared to John Creedy. John may have wrongly calculated that there were a lot of empty bags lying around in the maltster’s barn, and a few would not be missed. The search was carried out by Constable Joseph Durston, who found four empty bags and one with some oats in it, one wooden keg and about a quarter of a peck of potatoes (this is a volume measure, a quarter of a peck would be about 3 or 4 pounds of potatoes, depending on their size and weight.) John Graham said two of the bags belonged to him, Richard Cave claimed another bag, and Thomas Cape said that the keg was his. Gibbs the maltster thought that the potatoes had been stolen from him. John may have felt that the discovery of a few empty containers in his house would not be a big problem, and what happened next must have been a horrible shock.

John’s young brother in law, William Dawe, testified against him. The confession of William Dawe was described as ‘voluntary’, but William was only 17, and he was probably promised the commuting of a likely prison sentence if he turned King’s evidence.

The testimony of William Dawe, paints a picture of life in the Creedy household, and the unorthodox methods of John Creedy.

The voluntary confession and examination of William Dawe of Bridgwater aforesaid Labourer taken this thirty first day of October 1811

William stated that he was 17 years old, and the half-brother of John Creedy’s wife Mary. He had been having his dinner at John’s house for the last six months. One Saturday evening at about seven o’clock, William pulled up three quarters of a peck of potatoes on the field of Mr Gibbs (where he worked), and took them back to John Creedy’s house. This was probably William’s contribution to the family meal. John doesn’t seem to have been too impressed with the potatoes and asked William if he ‘had got e’er a duck’, to which William replied that he ‘could not get ne’er a one’.

William had met John as John was coming out of his house carrying on his back a three bushel bag containing about two bushels of beans. (A bushel is a volume measure of about 8 gallons). John asked for William’s help and William carried the bag on his back while John walked beside him. They walked to the stable of the butcher William Long, and put the bag down in the stable. Long then immediately tipped the beans into another bag, but as there was no light in the stable, William Dawe could not be sure. They all went into Long’s house, and while Long’s wife went out to fetch a quart of beer, Long paid John Creedy the sum of one pound for the two bushels just delivered and including four more bushels which John had brought previously. Long deducted one shilling and eight pence which John owed him for meat.

John and William Dawe then went to the nearby house of Edward Baker, and John paid Baker seven shillings and sixpence, although Baker complained that it was not enough a bushel. (It seems likely that Baker, Creedy and Long were involved in buying and selling beans at below market price, possibly because the beans were obtained illegally.) William Dawe and John Creedy then went home via the pub, calling in at the Bell Inn for two quarts of half and half. (In 1811, the Bell was an inn on the South side of West Street, on the site of the Cardiff Arms).

William, John, John’s wife Mary and her sister all sat down together for supper. Perhaps John was still hungry because after the meal he asked William if he would go with him to get some ducks, and William agreed. They went out together and began to walk towards Wembdon where there were several farms. The seventeen year old William was still naïve and probably had not anticipated that John wanted to make use of William’s insider knowledge of his employer’s farm. John asked William if Mr Gibbs had got some fat ducks and how the barn door lock could be broken. William was clearly anxious not to go to his employer’s farm and denied all knowledge of the ducks and the door lock, but John was not to be deterred.

When they arrived at Gibbs’ farm, William still insisted that he could not break open the lock, but John was adamant that William should get in somehow. William climbed up over the threshing machine and got on to the rafters of the barn. The intention was to wriggle along the rafters and get into the poultry enclosure, but unfortunately William slipped and fell painfully to the ground. At this point, William returned to John and complained that he had ‘fallen from a very high place’ and would not go in again. He begged John to give up and return home with him.

John refused to go, and reluctantly William had to climb up to the rafters again. This time he managed to get over into the poultry enclosure and open a window. William caught a goose, twisted its neck and dropped it into the bag which John was holding outside the window. William then caught and despatched two ducks in the same way. By this time the ducks and geese were making a great din and John thought he heard someone come into the barton. William hastily scrambled out of the window, while John declared that he would kill anyone who approached them with his stick. (This may have just been bravado on John’s part, there is no evidence that he was ever accused of violence).

They returned to John’s house, and that evening William, John, Mary and Elizabeth all sat down together and plucked and drew the birds, ready for cooking the next day. The next day, the three birds provided three meals – breakfast, dinner and supper for the four adults and three children.

William added that he had seen John take beans and oats to William Long’s house on another occasion, and been paid for them, but he did not know where John had got them. While the theft of a few empty bags does not seem a great crime to modern eyes, times were much harsher then. It also seems likely that the authorities had really hoped to catch John Creedy and William Long out in their ‘oats and beans scam’, but were unable to get enough evidence for this.

What happened next.

William Dawe and John Creedy were both admitted to Wilton Gaol on the 6th November 1811, and then transferred to Ilchester Gaol. William was charged, on his own admission, with stealing a goose and two ducks, but was discharged at the next sessions, Wells 13 Jan 1812, because he had given evidence for the prosecution. He was probably very unwelcome in the Creedy household after this, and seems to have left Bridgwater for a new life elsewhere.

John was charged on the oath of William Dawe, with stealing a goose and two ducks, and with receiving and having in his possession three bags, knowing that they had been stolen. John was convicted and sentenced to 12 months imprisonment at Ilchester Gaol. He was discharged on 13 Jan 1813.

Life after gaol

In the ten years between 1813 and 1823, John and Mary had a further five children and the family managed to stay out of trouble. However, after 1823 things began to take a downwards turn again. Between 1824 and 1838, three of John’s young sons – John (junior), Thomas and George all received convictions for petty thefts of vegetables, so it seems as though the family was struggling to get enough to eat.

On the 2nd of April 1827 John (senior) had another brush with the law. He was convicted of an offence against the Excise Laws. The offence was not described, but if John was working in the quay area, he could have been caught helping to unload a boat along the river bank away from the quay. The excise duties on goods (including coal) were heavy, and merchants had been known to try to unload their boats further along the river bank in an attempt to avoid paying the duty. The Description Book for Wilton Gaol gives a description of John. He was 55 years old, with a sallow complexion, grey eyes and brown hair. He was also described as unable to read or write, and having ‘vermin and the itch’, indicating that he was living in very poor accommodation. For distinguishing marks, he had ‘wounds in both legs’, perhaps scars from old injuries, or fresh wounds from trying to evade arrest. He was ordered to be detained until a fine of £20 was paid. This must have been a very large sum for such a poor family, but somehow it was paid on the 23rd of August that year. Perhaps the extended family had to rally round and contribute. John was discharged on that day.

Sadly in February 1828, John and Mary’s eldest child Sarah, now married to Francis Price, died aged 24, leaving behind a five month old baby and a three year old son.

This was followed in August 1829 by the death of their second daughter Charlotte, aged 10 years.

More duck thefts

The Creedy family hadn’t lost their taste for duck. On the 1st of July 1839, John’s son John junior and son in law Francis Price were convicted together of stealing one duck between them. John junior had two previous minor convictions for petty theft, and received a gaol sentence of 40 months in Wilton Gaol, Francis received a sentence of 30 months. Only six months later, the family were to realise that this gaol sentence was in fact a lucky escape for John junior.

John and Mary’s youngest son George had already had two convictions for petty theft of food. In 1833 aged only 11, he was sent to prison for three months with hard labour for stealing some onions, and in 1839, aged 17, he received another 3 months hard labour for stealing some apples. Then came a terrible blow for the Creedy family.

On the 17th of February 1840, the 18 year old George was taken into prison, accused of stealing three ducks and a drake, the property of Robert Skinner. At the Wells Spring Sessions on the 23rd of March 1840, George was found guilty and sentenced to be transported for seven years. We do not know why George received a much harsher sentence than his older brother for a similar crime, when both young men had two previous convictions for petty theft. Possibly it was down to the judges on the day. George was not transported immediately, he spent two years on the prison hulk ship Stirling Castle, moored at Devonport. He must have been a strong and healthy young man to survive the appalling conditions on board for so long. George was finally transported to Tasmania in April 1842, arriving in Hobart in August 1842. He never returned to Bridgwater.

As his whole family were illiterate, they probably never heard from George again. This sentence must have been a great shock for his family, and they largely stayed out of trouble from this time onwards.

1841 census

In April 1841, John’s wife Mary and his youngest daughter Harriet were living in Mount Street, Bridgwater. John should have been with them, but so far has not been found on this census. Mary was obviously having a hard time, both Mary and Harriet were described as washerwomen, and they were living in shared accommodation with twelve other people. As John and Mary’s three older sons had all left home, their income would no longer be a help.

Mary and Harriet were struggling to pay rent and feed themselves, as in 1842, Harriet, aged 18, got a conviction for stealing turnip greens. Her gaol description record described her as ‘slightly pock pitted’, indicating that she had survived small pox, an illness which was easily transmitted in overcrowded housing.

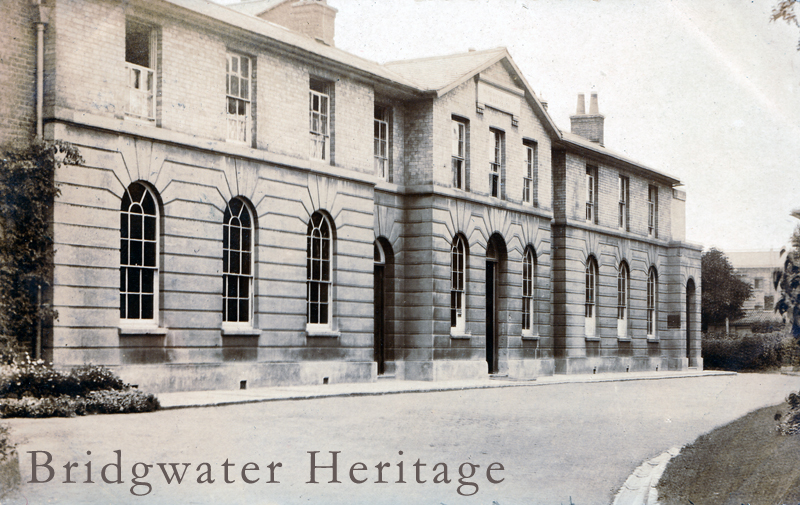

The Workhouse

John Creedy (senior) was not in the workhouse on the 1841 census, but some time after this he ended up in the Bridgwater Union, as he died there in August 1846. He may have been ill or injured, and had to go to the infirmary. John had a pauper’s burial in an unmarked grave in St Mary’s Churchyard on the 10th of August 1846.

Mary Creedy

John had a difficult life in harsh times, and his wife Mary must have had an even harder struggle. In 1849, when Mary was a widow living with her daughter Harriet, a cholera epidemic hit Bridgwater. In the space of two days in September, Mary lost three relatives to the disease. Her 25 year old daughter Harriet and 5 year old grandson Edward died on the 10th of September, and on the 12th of September her 3 year old grandson William died.

In 1851, Mary was lodging in Gold’s Buildings and living on parish relief. Mary died on the 10th of December 1852, and she was buried in the Pauper’s Section of the Wembdon Road Cemetery.

This is the story of my 4x Great grandfather John Creedy.

Clare Spicer 23/06/2020

With thanks to my cousins for their comments and advice – Chris Creedy, Hilary Southall and Jill Trethewey.

Sources:–

- Q/SR/383/106 Information of John Gibbs 20 Oct 1811

- Q/SR/383/104 Examinations of Joseph Durston and others 29 Oct 1811

- Q/SR/383/105 Confession of William Dawe 31 Oct 1811

Ancestry.com –

- Somerset Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials 1531 – 1914

- Somerset Marriage Registers, Bonds and Allegations 1754 – 1914

- Parish Register of St Mary’s Church Bridgwater.

- 1841 and 1851 Census of England

Bridgwaterheritage.org.uk –

- Friarn Research, descriptions of Bridgwater in the early 19th century by Charles Dibdin, Rees’s Cyclopaedia, Rev. J Nightingale and George Alexander Cooke.

- Bridgwater Industry Past and Present by Edmund Porter

- Lost Bridgwater – The West Street Area

British History Online (Victoria County Histories)