Does anyone know what became of ….?

Whilst digitising and editing for this web-site the text of Sydney Gaynor Jarman’s book The Bridgwater Infirmary. A record of its rise and progress, 1890, I noted throughout the book records of the gift of monetary presents to medical staff as they left or retired. It would be good to know what has happened to some of these Lost Things.

In addition, long standing Trustees or Honorary staff were given elaborate gifts of silver-ware, usually accompanied by a Testimonial Dinner at the Clarence Hotel.

Jarman recorded:

A Silver Tea and Coffee Service, 1867

RETIREMENT OF JOHN LILLY AS HONORARY SECRETARY OF THE INFIRMARY TRUST.

The Sub-Committee appointed in reference to the Testimonial to be presented to Mr. Lilly, reported to the Committee that they had selected and purchased a Silver Tea and Coffee Service, of the Princess Royal pattern, consisting of an urn, kettle, tea and coffee pots, sugar basin, cream jug, and cake basket, at a cost, to include the engraving, of £150; and that they had given directions for the following inscription to be engraved on each of the principal pieces

“Presented to Mr. Lilly by the Friends of the Bridgwater Infirmary, as a tribute of personal respect, and a mark of their appreciation of his zealous and energetic services as Honorary Secretary to that Institution during the past 16 years.”

A Silver Centre Piece, 1878

RETIREMENT OF MR. JOHN PARSONS, THE SENIOR MEDICAL OFFICER OF THE INFIRMARY.

As evidencing Mr. Parsons’ popularity and the high appreciation of his valuable services, immediately after the determination became publicly known, subscriptions flowed in from all quarters (and not the less gratifying were the contributions of several patients who had derived great benefit under Mr. Parsons’ treatment) until a sum amounting to more than £450 had been received. A Sub-committee obtained through Mr. James Rich, jeweller, &c., of Bridgwater, a magnificent and massive silver centre piece, with three figures, representing Benevolence, Esculapius, and Medicine, with three boy figures of frosted silver on the angles of the base, the base and shield being of gilt, with the arms and crest of the recipient engraved thereon, and beautifully, ornamented with foliage, ferns, and palms; and four dessert stands to correspond, the latter having also boy figures, with gilt bases. A case of six apostle spoons and sugar ladle of silver and gilt accompanied the centre piece. On the base of such centre piece there is an engraved inscription, of which the following is a copy :-

“Presented to John Parsons, Esquire, F.R.C.S., Senior Medical Officer of the Bridgwater Infirmary, by the friends and supporters of the Institution, and by patients mindful of its benefits, as an expression of their thanks for his gratuitous services and unremitting kindness for period of 33 years.”

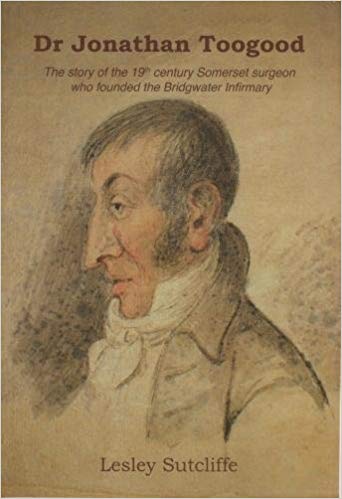

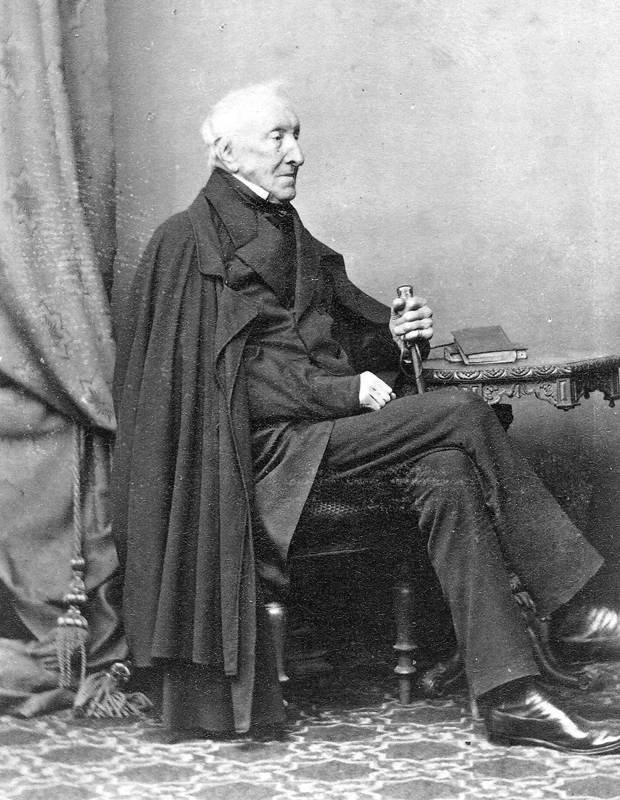

A Portrait of Dr Jonathan Toogood, 1845

In recognition of the long and valuable services of Dr. Toogood, extending over a period of 30 years, who from his extensive connection and influence had been one of the chief supporters of the Institution from the date of its establishment, a life-size portrait of Dr. Toogood was painted by Mr. William Baker, a native of Bridgwater, at the expense of £65 of the subscribers in the town and neighbourhood. The Rev. Noel Ellison, Rector of Huntspill, forwarded such portrait to the Committee, with a request that it should be placed in some appropriate part of the building. The following is a copy of an inscription on a brass plate affixed to the frame of the portrait:-

“Presented to the Bridgwater Infirmary by Subscribers to this Institution, whose names are recorded in the minutes of December 29th, 1845, as a testimony of their grateful sense of the gratuitous and highly valuable services of Jonathan Toogood, Esq, M.D., to this Institution for a period of more than 30 years.”

The artist William Baker was a son of William Baker, the Bridgwater natural historian. It is much regretted that the portrait is now missing and is feared lost to the town.

Found: Items relating to Rev. Bazell

In 1932, on the 50th anniversary of his ordination, Prebendary Bazell, Vicar of St John’s Eastover, was presented with an elaborately illuminated Testimonial book, with the names of the members of the congregation and school pupils. Following a house clearance it turned up on EBay in 2013, together with an album of Bazell’s photographs of late C19 Bridgwater. The Blake Museum purchased the Testimonial, and it now forms part of the Permanent Collection, and at the time of writing is currently on display. The album was purchased by Mr David Bown and subsequently published by him, with historical notes, as Bridgwater in the 1890s. Copies are available exclusively from the Museum shop for £14.95.

1931 Silver Salver

Following the opening of the new canal bridge in Victoria Road in 1931, the Mayor, Mr Frederick Oswald Symons, was given an engraved silver salver as a memento. This turned up on EBay in about 2010, but the Museum was outbid. It is now part of a private collection.

19th century Regalia of the King of Eastover

When I first became involved with the Museum in 2008/9 I read the minutes of the old Blake Museum Management Committee, then in Bridgwater Reference Library, and noted that in the late 1940s the Museum was offered by an antique dealer (and rejected) what was described as ‘The Regalia of the King of Eastover‘. This comprised a ram’s skull, the horns of which were decorated by silver, and a gavel. It was linked to a pub there. I infer from this that it related to what in London were known as Coal Holes – a room in a pub where folk did musical turns for the audience. These were ancestors of the Music Hall. The show was moderated by a chairman, with his gavel. Readers of a certain age may remember the 30-year run on BBC TV of The Good Old Days with Leonard Sachs. This gave a good idea of what was involved.

Powell’s Bridgwater in the Later Days (1908), pp.192-193 mentions:

Bridgwater also had other festivities and joys. Eastover, not to be outdone by the western side of the town, celebrated its revels, which long held sway with great success. Sports were arranged on the usual scale and in the manner common to West country towns, and the fun at these gatherings was fast and furious. The following note, published in a local newspaper on June 4th, 1832, might at first sight be a little misleading. It suggests a solemn municipal function:

“The Anniversary Dinner of the Mayor and Corporation of Eastover was held at the Globe Inn, on Tuesday last, Edward Bryant, jun. Esq, in the Chair. An excellent dinner and ample attendance was provided by Mr Thyer, whose endeavours to please were properly appreciated by a numerous and respectable party. It appeared to be equally the determination of the chairman and the company to avoid any topic that could by possibility break in upon the harmony which ought to prevail on such occasions. The party broke up at a late hour, highly pleased with the good feeling which had been displayed, and the good taste with which the duties of the Chair had been performed, under circumstances rendered unusually trying by passing events, and requiring no common degree of circumspection”

Eastover did not, as might be supposed from the above lines, possess a mayor and corporation, but it grew to be a sort of annual joke to seize upon some popular man, frequently the landlord of one of the inns, and elect him a sort of mock mayor for the occasion. A highly festive dinner was part of the programme, which was duly announced in the newspapers with all solemnity. On May 27th, 1833, the comong event was thus advertised:

“The annual dinner of the Mayor and Corporation of St. John’s Eastover, takes place on Wednesday next, at the Globe Tavern, when the Mayor elect will be installed with all the customary formalities. William Stradling, Esq., has been appointed to preside at the feast, and a numerous party is expected to honour the Mayor upon this occasion.”

… Mr Thyer, of the Globe Inn, proved to be a very popular Eastover mayor. It was the custom of the day to organise a great procession through the streets, through which the mayor of the day was carried seated aloft in a chair gaily decked with laurels. Various inn-keepers or other popular persons were chosen year after year. Mr York, landlord of the Ship Aground, took his turn in the high office; Mr Bullen, of the White Hart; Mr Jesty, of the Bunch of Grapes; and Mr Joseph Francis, the plumber. A greasy pole was erected near where Mr Waddon’s premises now stand, and the usual athletic contests, races, and so on were indulged in. The whole thing was got up to enliven the times and the people, and it was looked upon as an excellent joke.

What became of the Regalia I don’t know. Then, of course, the Museum concentrated much more on Robert Blake and the Battle of Sedgemoor. An interest in Social History did not begin until the 1950’s, after a report on the Museum’s Collecting Policy, by Dr F. S. Wallis of Bristol Museum, who recommended that the Museum’s scope was expanded.

There is undoubtedly more Bridgwater-related ceremonial material out there somewhere. It would be good to get it back for the Museum’s collection where possible.

A Silver Shield

In Chapter 20 of Jarman’s History of Bridgwater there is a mention of Colonel Kemeys Tynte who died in November 1860 aged 82. He had been Bridgwater’s Member of Parliament for 6 parliaments. The passage mentions a very interesting item:

“… [Two presentations were ] from the inhabitants of Bridgwater, in March, 1858, and again in 1860, the year of his death. The presentation in 1858 was a noteworthy one. It took the form of a massive silver shield, valued at nearly £200, and was beautifully engraved with pictorial representations of the old stone bridge, St. Mary’s Church, the Cornhill, Market House, &c.; it was also inscribed to the effect that it was an offering to one who had faithfully represented the borough in six successive Parliaments.”

The engravings were presumably based on Chubb’s illustrations of the old town, which had been later published through the support of the Tynte family.

Tony Woolrich 2 December 2019

Other Lost Things

Three Portraits from the Town Hall

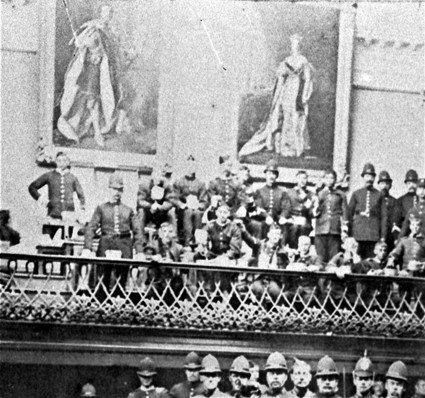

Jarman’s History of Bridgwater (1889) notes that in the main hall of the Town Hall:

Here are three life sized portraits, of great merit, painted by the late Mr. W. Baker, of Bridgwater. Two of these portraits, those of Queen Victoria and the late Prince Consort, were, according to brass tablets subjoined, Copied by permission of Her Most Gracious Majesty from the originals in Windsor Castle by Winterhalter, presented to the Borough of Bridgwater, in the year 1865, by John Browne, Esq., when this hall was opened. The third portrait is that of Alderman Brown himself, and underneath it are the words: This portrait of John Browne, Esq., J.P., was presented to him during his fifth mayoralty, in the year 1865, by the inhabitants of the town, and given by him to the Corporation to be placed in this hall.

These three portraits were not among the property of the town handed over to Sedgemoor District Council in 1974.

On 16th August 1900 there is a record that the painting of Albert had became quite badly damaged and the caretaker was due to be interviewed as to how this came about. As the hall was due for redecoration, it was decided to take them both down and get the Albert one restored. Victoria died very soon after, on 22nd January 1901 (with thanks to Mike Searle for passing on this information – 21 August 2023).

Another Portrait

The Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser of 12 October 1940 recorded the following:

SERVED WITH NELSON AT TRAFALGAR – FORMER BRIDGWATER BANK MANAGER – PORTRAIT FOR THE TOWN

The offer of a portrait of a Bridgwater man who served under Nelson at Trafalgar was reported to the monthly meeting of the Town Council.

Captain P. A. Thompson, of Brighton, wrote stating that he had in his possession a portrait in oils of a distinguished old Bridgwater man, Captain George Lewis Brown, and suggesting that the most suitable home for the portrait would be in the Town Hall or in some picture gallery in Bridgwater. Captain Thompson pointed out that Brown was born in Bridgwater in 1784. At the age of 13 he joined the Navy and served on H.M.S. Victory under Nelson, and at the Battle of Trafalgar he was second Signal Lieutenant on the Victory. Brown always claimed that it was he himself who suggested to Nelson one of the changes from the original draft of the famous signal “England expects.” Brown left the Navy in 1810 and after taking up farming and later practising as a barrister he was at the age of 52, in March 1836, appointed manager of the Bridgwater Branch of the West of England Bank, which post he held for 20 years until he died in 1856.

It was resolved to thank Captain Thompson and to accept the portrait for hanging in a suitable position either in the library or the Museum.

With thanks to Peter Randle for finding mention of this lost item.

The Holy Trinity Altarpiece and Stained Glass.

The picture below shows the interior of Holy Trinity Church before the 1876 restoration. The altarpiece is a copy of Guido Renni’s St John the Baptist, made by a talented local artist William Baker (1824-1870). What happened to this picture is unknown, as to why a picture of St John ended up in Holy Trinity and not St John’s in Eastover. The painting may have been sold to help pay for the 1876 restoration of the church, as photographs of the church after that date do not seem to show it.

Also missing from Holy Trinity are the stained glass windows, removed when the church was demolished in the 1960s. The Western Daily Press of 2 February 1914 reported:

The East window of this church has just been fitted with stained glass, which was yesterday dedicatedby the Bishop of Bath and Wells. The window consists of four lights and tracery, and the subject represented is “The Resurrection Morn.” The dominating figure is the Angel Messenger, who, seated at the entrance to the rock-hewn tomb, with arm upraised, is announcing to the Holy Women the joyous Easter message: “He is not here, for He is risen, as He said. Come see the place where the Lord lay.” The colouring throughout the window, as befits the subject, is soft and subdued in tone. The quiet and carefully blended shades of blue and purple in the robes of the Holy Women the soft tints of the foliage, the neutral tones in the rock work of the tomb, and the grey sky of dawn are all subservient to the rich ruby wings and the pale garments of the Angel. A distant view of the hill of Calvary, with the three crosses outlined thereon, the scattered grave clothes, and the box of precious ointment are amongst the details which add interest and refinement. The window was executed by Messrs Joseph Bell and son, at their studio at 12, College Green, Bristol, under the supervision of Mr P Hartland Thomas, diocesan surveyor for Bath and Wells. The work is undoubtedly a very handsome addition to the church.

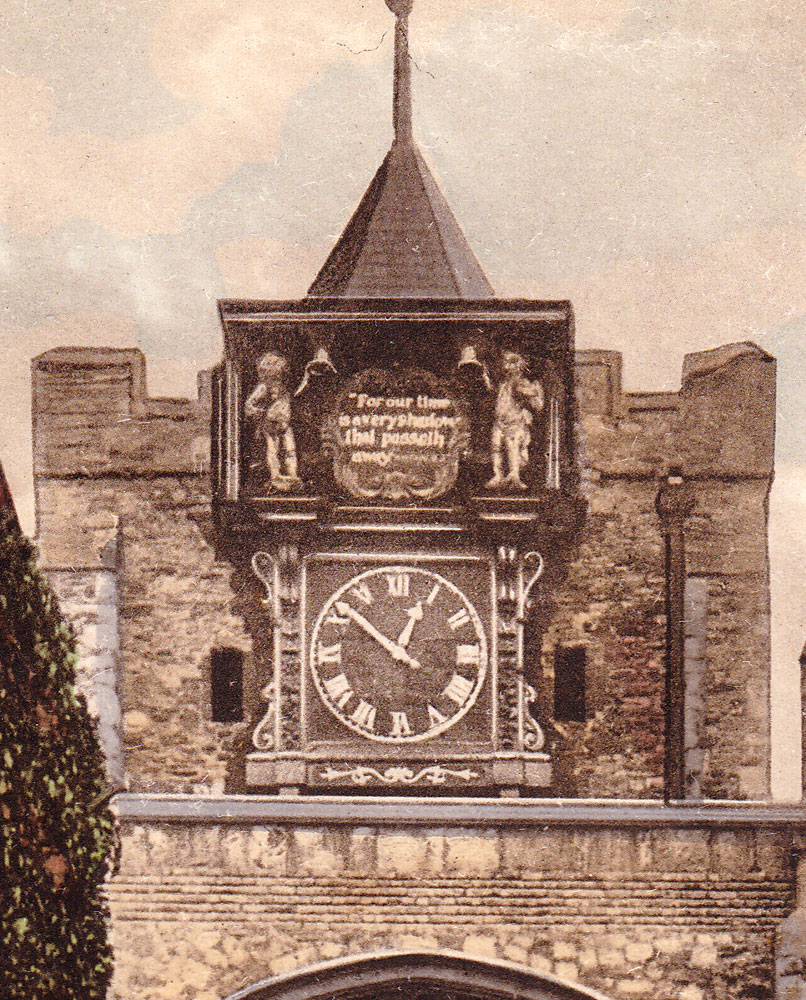

The striking figures from the Gaol Clock.

[T.Woolrich]

George Parker wrote a poem for a fund-raising exhibition in the Town Hall to help pay for the Restoration of St Mary’s Church. It took place in November 1854. In the Notes is the following passage:

A handsome cross once stood on the Corn Hill. Between it and the Bridge stands the old Jail, over which is a clock; some years since the hours were struck by two large antiquated wood figures on two excellent bells. They held in their hands a sort of battle axe, and their arms were moved by means of springs. When the old Town Hall [this same building] which stood there was removed, and the building became altered, these figures were taken down and sold by order of the authorities, which is to be regretted. I have heard, at some Election freak, a platform was made at night upon the Cornhill, and those two figures craftly removed there; where, in the morning, they appeared dressed as representing two of the Candidates.

Bridgwater Items Kept at Chilton Polden Priory

From A description of the Priory of Chilton-super-Polden, and its contents by William Stradling, 1839, page 6:

In a nich in the porch, is the lower part of a figure clad in Priestly robes, the toes of the shoes sharp pointed, and resting on a dead lion, found in the ruins of St. John’s Chapel, Bridgwater, and from the remains of paint on it, etc, is supposed to have been part of the tomb of one of the family of the De Brewers, who were great benefactors to that Hospitalm and also founders of the Parish Church. This probably represents a person who in early life was a soldier, and afterwards became an ecclesiastic (presented by Mr. Josepth Francis). Below is the top stone but one of Bridgwater Spire, which, after having braved the blasts of nearly six centuries, was so much injured by lightning as to be rendered dangerous, and therefore partly taken down and restored. In the corner at the right is a large stone ball, shot into the town of Bridgwater during the siege by General Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell, and lodged in the wall of the old White Hart Inn, in Eastover, lately burn.

pages 11-11

…on this stand is an iron hook which supported one of the eastern gates of the town of Bridgwater. To which, tradition says, several of the rebels were hung, after the Monmouth’s flight in Weston Moor on the 6th of July 1685.

A bust of Andrew Carnegie

From the obituary of James Cook Jnr, Bridgwater Mercury 29 November 1911:

He was present in September 1906, when the new Carnegie Library was opened in the Blake Gardens, and was mainly responsible for the possession of a stone bust of the millionaire donor, which is a conspicuous feature of the handsome buildings.

Possibly lost when the library caught fire in 1978?

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

A statue of Napoleon I

In the large niche on the side of Castle House (the ‘Concrete’ or ‘Portland’ Castle) in Queen Street was a concrete statue of Napoleon Bonaparte. This was removed in the 1980s and its location now unknown. A photograph of the statue can be seen here.

Memorial Plaque from Wembdon for Thomas John Berry

Somewhere near the old Post Office and Stores in Wembdon was a memorial plaque for a Thomas John Berry, who was killed there in an accident in 1890. It was still there within living memory, but the exact location and its fate remain unknown. The Weston Mercury of 6 December 1890 recorded

BRIDGWATER. SHOCKING FATAL ACCIDENT —Shortly before midnight on Wednesday, Mr Thomas George Berry, 19 years of age, and son of a farmer at Dodington, was riding home from Bridgwater, and when going down hill near Mr Akerman’s residence at Wembdon his hone stumbled and fell. Mr E. K. Babbage and Mr Jarvis, of Bridgwater, were near at the time and on going to Mr Berry’s assistance found him lying in the road insensible. Medical assistance was speedily obtained, Dr Marsden being soon in attendance, and the unfortunate young man was removed in a cab to the Brigdwater Infirmary. He did not recover consciousness, and died in the institution about four hours after his admission, through, it is believed, the rupture of a blood vessel. The deceased was a member of the Bridgwater Troop of the West Somerset Yeomanry Cavalry, and was much respected.

Additions MKP