Extracts from Charles Robert Browning Barrett (writer and illustrator) Somersetshire: Highways, Byways and Waterways. Published in London by Bliis, Sands and Foster in 1894

CHAPTER X. (pages 254 to 269)

BRIDGWATER AND SEDGMOOR.

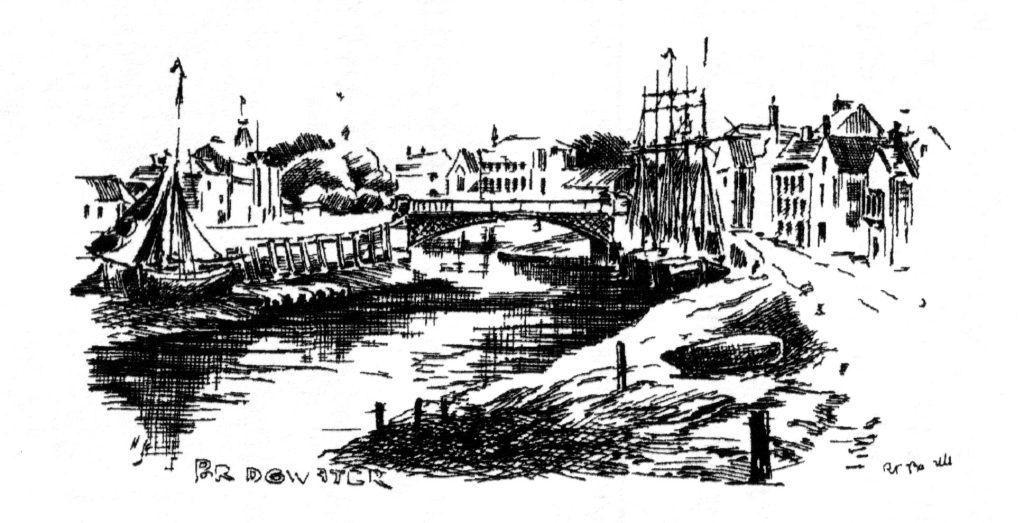

THE ancient borough of Bridgwater has changed its outward appearance nearly as much as IIlchester, since the days when old Leland “enterid into a Suburbe, and so over a Bridg, under the which renneth a Brook, that risith 4. Miles of by West at Bromefelde.”[1] It was even then going to ruin, and the worthy antiquary noted that “the Castelle, sumtyme a right fair and strong Peace of Worke,” was a wreck. Of the religious houses the domestic buildings of the college of “Gray Freres” were in existence then; but in these days an arched door in Silver Street, if my memory serves me aright, is the sole relic thereof. The “Chapelle of S. Salviour at the South side without. the Towne, which was buildid in hominum memoriae by a Merchaunt of Bridgewater cawIlid William Poel or Pole,” has vanished completely, and the same remark applies to the college of St John, the only thing “notable” in the “East Part of the Town.” This college is called by Leland “late,” as if then unoccupied. It stood partly without the East Gate. To it adjoined “an Hospital for pore folkes,” and it appears that the costumes of the priests had been that of secular priests with a “Crosse on there Breaste.” The house of the Grey Friars was then in the occupation of the “Accustomer” of Bridgwater, who had “translatid” it to a right goodly and pleasant dwelling house. Leland also mentions another hospital built and founded by the townsfolk, but “endowed with little or no Lande.” Of the ancient three-arch stone bridge over the Parret, we read that it was “stronge and high,” and that it was begun by William Briwere the first lord of Bridgwater, in the time of Richard I and John. This famous bridge was finished by a certain Triveth or Trivet, a man of “Devonshire or Comwalle,” and thereon he placed his arms “in a Shield yn the coping of the Chekes of the Bridge.” The old bridge endured from his day till the year 1795, when it was taken down to be replaced by an iron structure. My sketch, taken from the new London and South Western Railway swing bridge,[2] shows the present appearance of the old port of Bridgwater.

Leland makes no mention of the very curious market-cross which formerly stood on the Cornhill opposite the entrance to High Street. This market cross was notable from the fact that it contained, in its upper part, a cistern to which water was laid on to pipes from a certain mill known as the Queen’s Mill. In form it was hexagonal, with flat-arched openings and a crenelated parapet. Curious bamboo-shaped buttresses stood at each corner, and terminated in plain elongated conical pinnacles. Similar pinnacles also projected upwards from the crown at each arch. A band of quatrefoils ran round just beneath the crenelations, except on one side, which lacked both crenelations and quatrefoils, but bore a sun-dial. The pertinent inscription, ” Mind your own business,” was sculped on this interesting market cross. Alas, all vanished about the same time the ancient bridge.[3]

But though ruinous in the days of Leland, the old castle of Bridgwater was destined to play a part, and an important part, in the county history more than a century later. Of this I shall speak presently. Nowadays there is unfortunately but little remaining to us of this historic spot. Built, like the bridge, by William de Briwere, it probably shared in the discomforts attaching to the capture of the town by the barons doing the reign of Henry III. The only relic of the castle visible at the present day is the archway of which I give sketch — an archway which, in all probability, formed the watergate of the stronghold. Some arched cellars beneath a house a few feet distant are stated to have also belonged to the foundations of the castle defences; but these, I was given to understand, had been bricked up quite recently, owing to the constant irruption of the tide, which rendered them useless.[4] The main buildings of William de Briwere’s stronghold occupied the open space now known as the Square – a site on a rising ground a little drawn back from the river and approached by walking up Chandos Street. Here, not so many years age a few walls were yet standing; and a portion of the fosse, even then thirty feet deep, was visible. The castle well, a very large one, is believed to have been situated in one corner of the present square. It should be mentioned that a “castle bridge,” distinct from the ” three-arch” bridge existed formerly, and I understand that a few fragments of its masonry are at times to be seen when the tide is very low.

Bridgwater was never a walled town, though possessed of four gates, known as the North, south, East, and West Gates. Leland states that the “Waulles of the Stone Houses of the Toune be yn steede of the Towne Waulles.” But despite its then decaying condition (two hundred houses recently gone to ruin), the borough of Bridgwater must have been a most picturesque place in the days of Leland. That it is not so now is mainly owing to the making of its history, as I shall presently show. First, however, it will be more fitting to notice the church of St Mary and such other buildings of antiquity as remain —few enough, alas; At for their rarity there is ample reason.

St Mary’s Church is large and possesses one feature which in this county I have already alluded to as being uncommon, viz. a spire. In style the architecture is mainly Perpendicular; but touches are observable of Decorated work, which may safely be assumed to be fragments of a former church. Externally the most interesting portion is on the north side, where near the ground level some curious arches are visible. A most extraordinary series of hagioscopes was destroyed some years ago.[5] These hagioscopes gave a view through three different walls, so that a person standing it the porch had a perfect sight of the high altar.

On first entering the church I was struck by the large amount of carved woodwork. That the chancel roof was modern I could at once discern, but with the side screens there it is far different.[6] These are of late fourteenth-century date or I am much mistaken. They are handsome and extremely well preserved.[7] By no means so ancient, of course, though equally well kept, is the Jacobean screen or grille which partitions off the seats appropriated to the corporation on the south side of the church.[8] How different the condition of these, which evidently show that loving care has been bestowed on them, from the rotted corporation benches in the north aisle of the tumble-down Orford chapel in Suffolk. Above the altar is a large and valuable picture of which the subject is “The Descent from the Cross.”

The story of this picture is somewhat remarkable. According to tradition it was taken out of a privateer, of nationality variously stated as Spanish or French. In some way the Hon. A. Poulett (his name in fact was Anne, after his royal godmother) became possessed of it. At that time he was one of the Members of Parliament for the borough, and presented this painting to the mayor and corporation, with a proviso that it should form the altar-piece for the parish church. The picture is one of great beauty, and it is somewhat remarkable that hitherto the painter thereof has remained unidentified. It has been suggested that its origin is either Spanish, Italian, French, or Flemish—a suggestion which includes a fairly wide number of schools! Flemish it certainly is not; French I should consider it impossible for it to be. There remains but a Spanish or Italian origin, and of those, speaking not as an expert in any way, I should be inclined to reject the first named. But in these days it seems extraordinary that no absolute clue has ever been obtained to clear up the mystery attaching to the painter of this noble work of art. In Bridgwater I was told a curious story that Sir Joshua Reynolds on more than one occasion went out of his way to visit the church and study the painting and composition of this picture. If true, this speaks volumes for both its beauty and its artistic value.[9]

One tomb in the churchyard needs notice. It is that of a native of Bridgwater, John Oldmixon, who was born in 1673. He was a prolific writer, being the author of a “History of the Stuarts” a “Critical History of England,” and a “Life of Queen Anne,” besides various pastorals, plays, criticisms and political pamphlets.[10] His political services obtained for him the post of collector of customs at the port of Bridgwater, while his abusive attacks on various men of letters obtained for him the distinction of being ridiculed in the Tatler, under the none of “Mr. Omicron, the Unborn Poet.” Pope, whom he had abused, accorded to him the questionable honour of mention in the Dunciad, where he is represented as mounting the side of a lighter in order the better to plunge into the mud of the Fleet ditch. Oldmixon, in his writings, was a fierce opponent of the house of Stuart, and was guilty of making a most false and shameful accusation against three persons —Dr. Aldrich, Dr. Smallridge, and Bishop Atterbury—two of whom were dead; viz. that they had interpolated certain passages in Lord Clarendon’s History. Bishop Atterbury, the survivor, refuted this calumny, writing from his place of exile in Paris, October 26, 1731. The story will be found in full in the Gentleman’s Magazine, Vol.1, p.514, and vol. iii. pp. 117,129..140. Oldmixon died in 1742.

A very remarkable manuscript account or inventory of the vestments and furniture belonging to St Katherine’s aisle in the church of St Mary’s Bridgwater, is still among the corporation archives. To this list is appended a statement of the rents which were then the property of the aisle. The document, from its character and phraseology, appears to be of fifteenth-century date. From the list, the aisle of St Katherine must have been fairly well equipped with both vestments and furniture. One or two entries are remarkable, such as a “quer of Commemorations” and “ij steyned clothes to stand bifore the Tablemer in ye lent tyme.” The materials used for the vestments, altar-cloths, and hangings were not by any means costly, four only being of silk, while the remainder were damask, worsted, “chekered” (probably some inexpensive stuff in squares), “Bustyan,” diaper, plain cloth, and ” Howlond” cloth (?Holland). A mass book with two silver clasps and a chalice weighing nineteen ounces comprise the plate. There were four “sacryn belles,” three pairs of candlesticks, two “cruets of tyne,” “ij corpas with ij cacys,” and three “steyned bannarse.” The plate certainly was but a meagre supply, though possibly some of the bells and candlesticks were of silver. For the above details I am indebted to the paper of the Rev. W. A. Jones, “Som. Arch. Soc. Proc.,” vol. vii.[11]

Close by the churchyard on the north side, and separated only by a narrow pathway, stood, until a few months ago, a very beautiful old house, rich with carved wood decoration, both within and without. It is most grievous to think that this has been entirely demolished, to be replaced by an ugly red brick dwelling—even more grievous when we consider the scarcity of half-timber houses in the county, a scarcity which I have previously mentioned.[12]

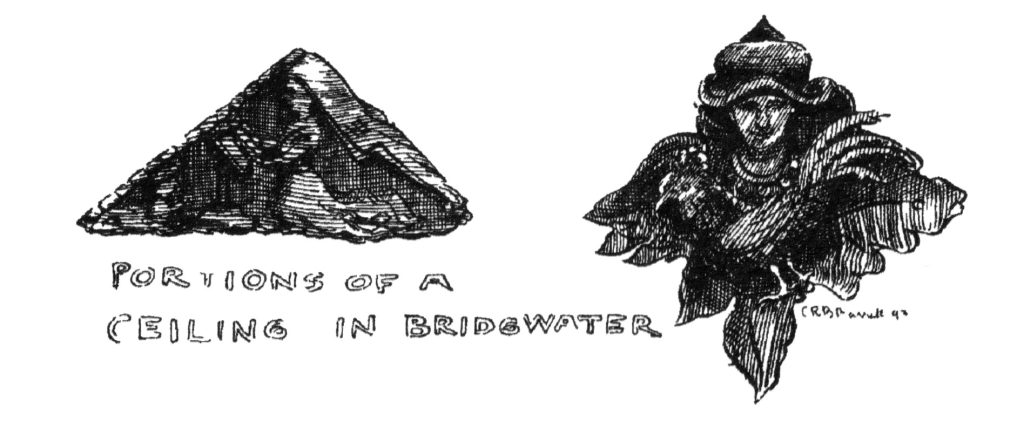

In a house at the east end of the churchyard, now used as refreshment rooms, there is a very remarkable ceiling, from which I derived the two details here illustrated. This ceiling has twelve panels, divided by massive well-moulded beams, and decorated with very quaint bosses. My sketches show two of these and the most remarkable of the remainder have for their subjects four pigs or boars intertwined, a tomfool, an ecclesiastic and lion, a demi-figure clutching a fiend, and an animal devouring grapes. Behind some matchboarding, which has quite recently been nailed on to the staircase. I was told that some beautiful carved “windows” exist, but I suspect that these ” windows’. are in reality the remains of a screen.[13]

There is one house in Bridgwater which, though unpretending, nay, even uninteresting in its exterior, from its associations needs a few words: I allude to the birthplace of Robert Blake. This house stands at the bottom of Blake Street, close by a little foot-bridge which spans the brook. The view up this brook, of walls, buttresses, and tenements is in its own way picturesque, but I did not tarry, to sketch it. The interior of “Blake’s House” contains one room of which the panelled ceiling is an interesting specimen of its date; and there is also a fair fireplace. In the passage on one side of the house I discerned traces of old work now half concealed by whitewash.

[Here is a summary life of Admiral Blake and the Story of Bridgwater in 1645]

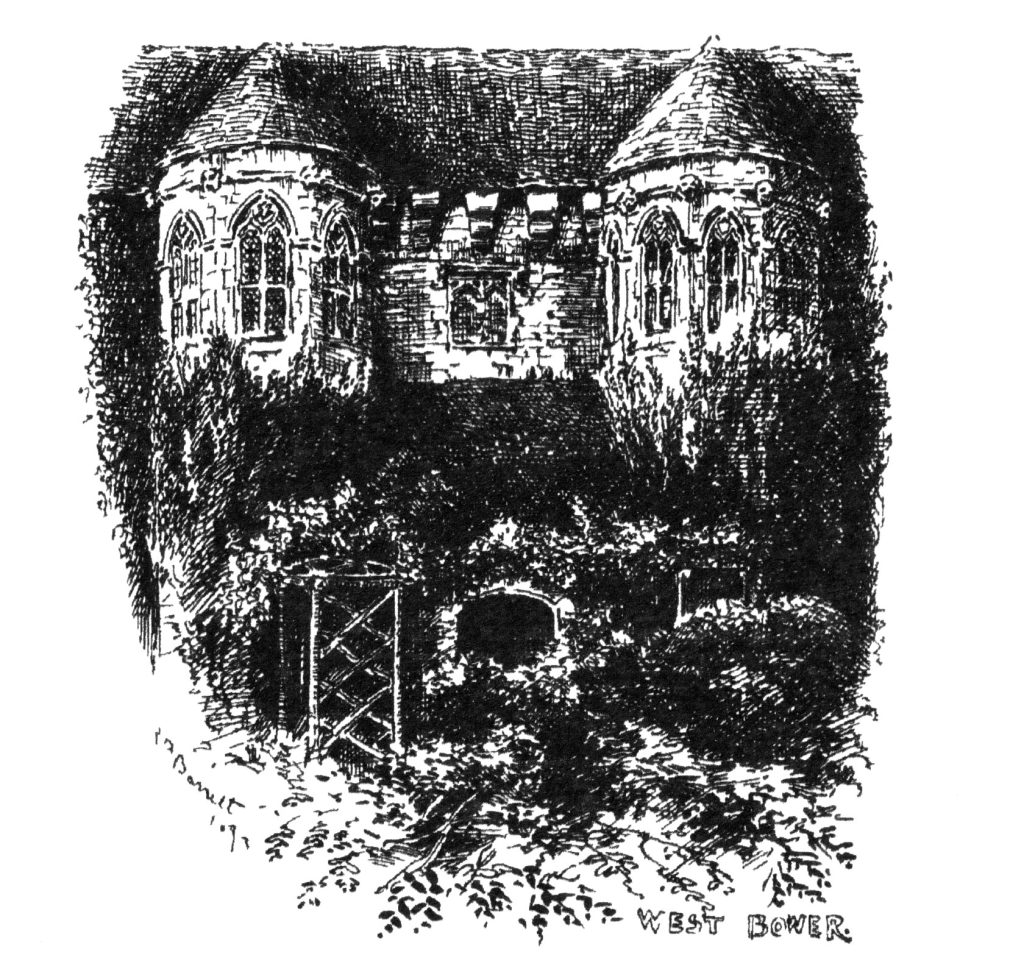

Before making my way from Bridgwater to the equally historic Sedgmoor, I rambled for a short distance in a westerly direction to visit a most picturesque old manor house not far from Enmore Castle, but in the parish of Durleigh. It is known now by the name of West Bower Farm. My reception here by the occupier, Mr. Talbot, was most kindly, and I was freely permitted to thoroughly inspect this interesting fragment of an old-time manor house.

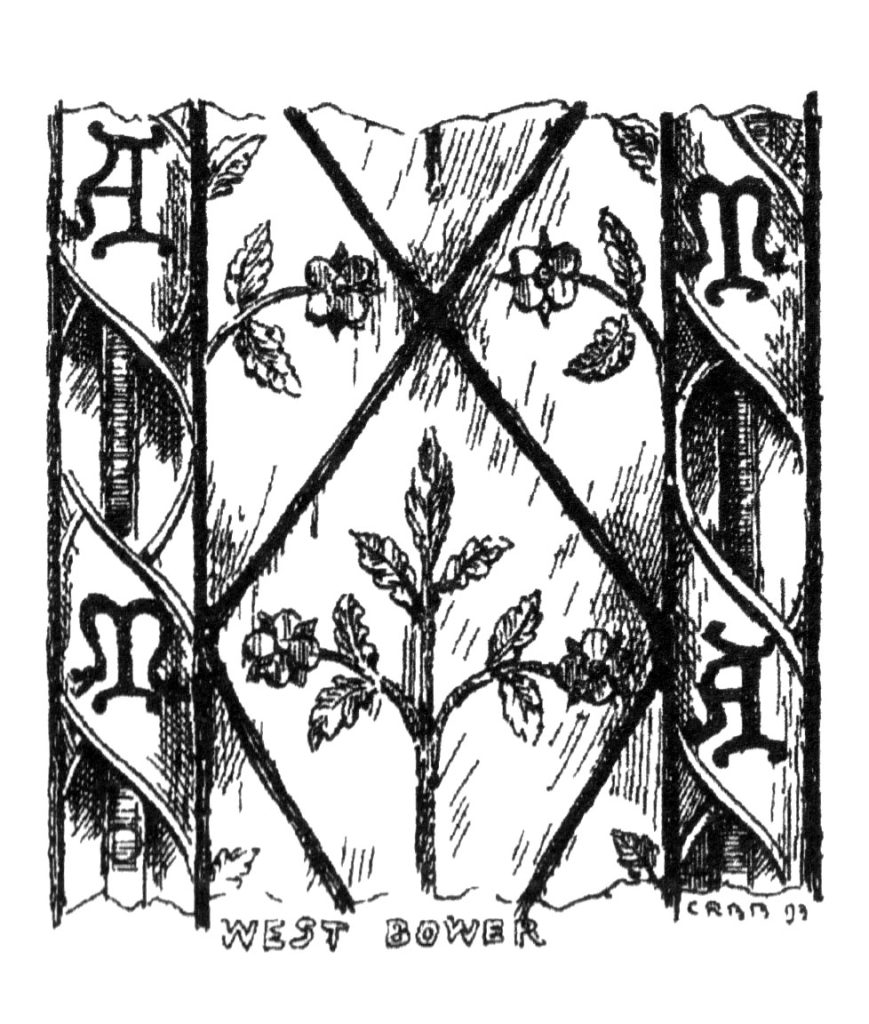

My sketch shows the general appearance of this quaint old place whose creeper-clad sides and wild-garden surroundings form in the summer or autumn tide a sufficiently pleasing picture. The porch roof between the turrets is, it is almost needless to state comparatively modern. By means of a low flat arch I entered the house, and found an inner arch of larger size within, but this is cut by a modern ceiling. There are four arched doors in this vestibule, of which three are moulded, while one in front is plain. A fifth door arch which was to be looked for appears to be lacking. A well with a pump is in one corner. I next inspected the turrets, and was delighted to find in the windows some of the charming glass of which I here give a sketch.

From what I can learn West Bower belonged long ago to the Malets, and possibly the initials in the glass refer to some member of that family. In the right-hand turret room there are small windows amounting in number to twenty lights. Upon each side are two stone panels which are blank, while the old door is surmounted by balusters. The left-hand turret contains a stone newel, and is entered by a low flat-arched door. Above the windows on the inside are three shields and two ornaments, which are repeated in the tracery on the outside. There are fragments of the same glass in this turrett, and I also noticed a peculiar swelling in the centre of each mullion somewhat similar to the pierced knob in the window at Meare. There were also traces of shutter-hinge hooks. Unfortunately the vaulting of both these interesting turrets has been removed. It is not, I believe generally known that the columbarium at Wet Bower is perhaps the most remarkable specimen in the county. It is circular in shape, of large size, and with the exception of its thatched roof built entirely of mud. The nesting niches number nearly nine hundred, and are formed in the mud wall, which is actually more than three feet in thickness. It should be noted that West Bower Farm is but a fragment of the original manor house. Foundations have frequently been met with in the garden and yard, which prove that the extent of the place when perfect must have been very considerable. At West Bower I was told that, traditionally, it was the birthplace of “Queen Catherine” This statement could only refer to either Catherine Howard or Catherine Parr. But on reference I find that the tradition has no warrant in fact.

The road to the battlefield of Sedgemoor is not picturesque, and were it not for the frequent orchards laden with ruddy fruit at the time of my visit, I should have unhesitatingly celled it ugly. Muddy I can assure the reader that road was, and, indeed, my expedition to Weston Zoyland and its sister parish was the most unpleasant, as far asthe weather was concerned, during my entire trip.

[on to Westonzoyland]

[1] See this page for Leland’s notes on Bridgwater.

[2] The Black Bridge/Telescopic Bridge.

[3] See this age for notes on the High Cross.

[4] Possibly the cellars under the old Watergate Hotel. These were accessible in the 2000s, but when the river wall collapsed they were inundated with mud.

[5] These are also referred to in the literature as ‘squints’.

[6] The ceiling actually has some fine medieval bosses mounted to the Victorian work, although Barrett can be forgiven for missing these, given how high up they are and surrounded by Victorian work.

[7] The Rood Screen.

[8] The Corporation Pews.

[9] See this page for more on this painting.

[10] Oldmixon is not actually buried there, but relatives are. See this page. In the time Barrett was visiting it was thought Oldmixon was there, so again, he can be forgiven.

[11] See this page for the full inventory.

[12] The demolished building is almost certainly 23 High Street – rebuilt in 1892 for Mr Curry.

[13] This is the famous Burrell Ceiling. The screen is now in St Donat’s Castle in Wales. Barrett is the first datable account of the ceiling after its discovery by Mr Pitman. It was sold in the 1920s to Hurst the American newspaper tycoon, and then to Sir William Burrell. It can now be seen in Glasgow.