‘How it came to be’ is by Tony Woolrich and was originally one of a series of booklets written for the re-ordering fund raising.

Introduction

It is quite wrong to think that the Saint Mary’s today is an unspoiled medieval gem, or even an unspoiled Victorian one The history of Saint Mary’s building has been one of continual development to cater for changes in the liturgy, in ecclesiological taste and in the needs of the congregation; it has always adapted to the needs of the time and is not a museum piece. The stonework continually degrades and is in need of constant repair.

The origins of Saint Mary’s are not known with any certainty. Remains of Christianity dating from Saxon times have been found nearby at Wembdon, Cannington, Combwich and North Petherton, and it is reasonably certain that Christianity flourished in those times in Bridgwater as well.

It is possible a simple wooden building pre-dated the formation of the Borough in 1200, but it was not until after that date, perhaps coincidental with the construction of the castle and the bridge over the Parrett, that the first stone church was built The name of the first vicar of Bridgwater was recorded in 1170.

The Medieval Church

For much of the Middle Ages Bridgwater was a prosperous port and market town, and Saint Mary’s was often extended and modified. In the thirteenth century it was aisled and was extended westward and by transepts in the following century, when work was also done on the tower. By 1400 it had three chapels as well as the high altar and the rood, and eight priests served it. In the fifteenth century much work was done rebuilding and extending the chancel, making three more chantry chapels and a rood screen and modifying the nave.

In medieval times the focus of the religious service was the altar at the east end of the building. This was concealed behind an elaborate carved and coloured screen, which ran across the Chancel arch. Above this hung the Rood, the hook for supporting which can still be seen in the apex of the Chancel Arch. The religious ceremonies were carried out separate from the people, who took no part in them and who could only stand outside the screen and watch. At that time the east end of the church was on the line of the present steps separating the chancel and the sanctuary. The area around the altar was highly coloured and lit by many candles. The surviving churchwardens’ accounts contain many references to the purchase of candles and vestments. Saint Mary’s also had three chantry chapels, and seven guild altars served by mass priests who lived in cottages around the church. A squint was also constructed to allow sick people such as lepers, who were barred from entering the church, to see the ceremonies from the north porch.

Apart from the basic floor plan all that survives of the medieval church is the tower and spire, some walling round the northern flank of the building, the pillars separating the nave from the aisles and a handful of ornamental carvings, such was the comprehensiveness of the Victorian rebuilding.

Little is known about the music used in Saint Mary’s then, but various leaves from illuminated service books were recovered from the bindings of the Bridgwater Borough records during the last century and may be seen in the Heritage Centre archive office at Taunton.

The Reformation and Protestant Worship

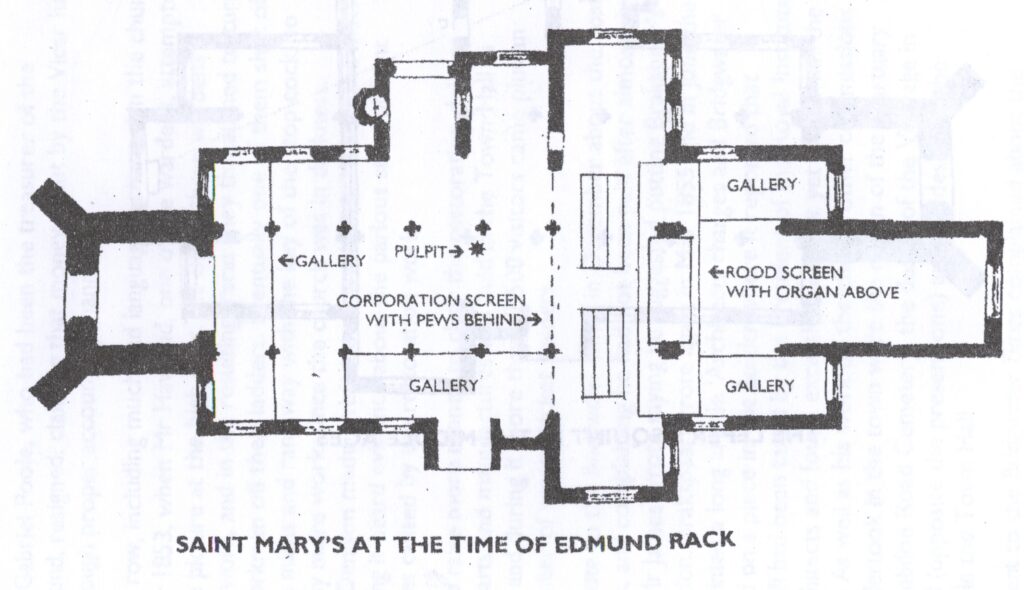

Radical changes in theology and ways of worship occurred after the Reformation. Preaching became far more important than before, and the layout of the church was adapted to allow this. The Rood and the various chantries would have been removed by the middle of the sixteenth century, and soon after a pulpit was built against a pillar in the middle of the church, where the preacher could be heard by all the people. In the seventeenth century special pews, facing west towards the pulpit for the Corporation, were built in the nave behind a carved screen parallel to the medieval screen. Box pews were installed, and during the eighteenth century various galleries were built as well.

The first authoritative account of the appearance of the inside of the church was written in around 1785 by Edmund Rack (1735?-1787). He was a resident of Bath and collected a mass of topographical material about Somerset which remains unpublished, though John Collinson had access to it when he wrote his History of Somerset, 1792.

The church (which is dedicated to Saint Mary) is a large and handsome gothic structure 156ft long and 88ft wide, consisting of a nave, chancel, north and south ayles [,] vestry room, belfry and 2 porches all covered with [MS blank]. At the west end is a Tower 60 ft high with a spire on its top 114 ft high, the whole height being 174ft This tower contain[s] a clock and chimes and 8 bells The outside of the church, tower and spire is whitewash’d.

The nave roof is 35ft high archd and ceild with the ribs of the arch projecting. Chancel roof 32ft arch’d and Ceil’d also. The roof of the ayles 25ft flat and open to the timbers. Each of the ayles is divided from the nave by 6 arches 12½ feet wide and 21 high. The pillars that support them are light and handsome Those on the south side 12ft high to the spring of the arches – on the north side 13 ft All of them are 5½ ft in circumference.

The altar piece is an admirable painting of Raphaels* – the subject is our Saviour just taken from the Cross. This painting is 8ft wide and 13 high, in a very elegant gilded and carved frame surrounded by very elegant emblematical figures in plaister of Paris on a dove coloured and blue ground On each side [of] this painting are 2 very handsome clustered pillars in stucco with Corinthian Capitals terminated in 2 superb flaming urn[s] girt with gilded foliage. This altar piece was given by the Hon Ann Paulet member for this borough in the year [1775]…

The Communion table is very antique and curiously carved and enclosed within an elegant iron Chinese railing embelished with gilded stars and top’d with mahogany. The chancel is divided from the nave and ayles by a curious open work Gothic screen over which is an organ loft with a large fine toned organ in the centre and galleries to the right and left in the front of this gallery are the Royal Arms and 12 other coats in the pannels of the wainscot belonging to the families who subscribed to the organ There is also a gallery half the length of the south ayle, supported by a large clustered pillar 6ft round and 8ft high. In front of it a set of 4 fluted pilasters of the Corinthian Order with a Cornice and a panelled front above it.

At the west end of the nave is a good gallery for the singers supported by 4 square fluted pillars Wth a Doric cornice and panell’d front above it. In front of the Organ loft are 6 pews inclosed within a very antique and curious open arch’d screen on which is a profusion of fine ancient carving The spot thus inclosed is called the Mayor’s Ayle and will hold the whole Corporation.

The pulpit and reading desk are very ancient and curiously carved in small Gothic arch’d work. In the centre of the church is a fine brass chandelier of 30 sockets – 10 in each row. The church contains 5 doors and 37 windows, are large and handsome, being crownglass and wir’d without side. There are also 192 pews, many of which are large and good, but mostly of old painted wainscot and some small and ordinary. The pavement is very good and almost covered with inscriptions, the most memorable of which will be given in their order The church is very dry and kept very clean and decent…

* Note, Rack’s attribution of the authorship of the painting is not supported by modern scholarly opinion.

Very little has so far been discovered about the musical life of Saint Mary’s before the nineteenth century. The Sherborne Mercury in the 1730’s carried advertisements for the appointment of a church organist. The Book of Common Prayer made no provision for the use of metrical psalms and hymns, and indeed it was unlawful to use them during the services until 1822; the only sung item permitted was the anthem after the third collect in Morning and Evening Prayer. Hymn writing developed during the eighteenth century through the activities of the Methodists and various non-conformist writers, and particularly in evangelical and rural churches (which rarely had organs) the practice grew up of the singing being led by a choir accompanied by a small band of string and wind instruments.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century England was dominated by two philosophical doctrines, Utilitarian and Evangelical. Both were opposed to the Church of England. The church did not try to respond to the imagination with stately liturgy, performed with ceremony; instead, the clergy gave cautious sermons in bleak churches.

The Church of England of the 1830s differed greatly from what most people think of as the church today. Chancels and altars, clergymen in surplices, anthems, festivals, frequent standings and kneelings -these form part of everyone’s image of the Anglican Church. To a good Protestant of 1830 the least suggestion of symbolism – a cross on a gable or on a prayer book cover – was rank Popery. All forms of ritual were equally suspect The clergyman wore a black gown and read the communion service from his pulpit; no one knelt during the longer prayers, or stood when the choir entered; indeed the choir, if it existed at all, was hidden in a gallery, where it performed to the accompaniment of violins and a cello. The old Gothic churches had been gradually adapted to this style of service. Features such as piscinæ and sedilæ were abolished; since altars were seldom used, even as tables, the chancel was either abandoned or used as a vestry, and whatever symbolical sculpture existed in the nave was concealed by massive comfortable pews for the rich and galleries for the poor.

The Tractarian movement grew up in the early 1830’s in reaction to this lethargy and indifference. Unlike Luther and Wesley who looked back to the very early church for theological purity of worship, the Tractarians looked to the Middle Ages, which in turn meant Gothic architecture. Various societies were formed to investigate and publicise the architectural aspects of the church buildings and the liturgy carried out there, which in effect meant full Catholic ritual. Architects were drawn into the movement with the result that very many perfectly acceptable historic churches were altered or often completely rebuilt, with varying degrees of scholarship and competence to mirror the Tractarian view of how a church should be. The population of Bridgwater grew in the first part of the nineteenth century, and by 1831 had risen to 7807 from 3634 in 1801. A survey by John Bowen, Churchwarden at Saint Mary’s, made in October 1830 showed that Saint Mary’s could only seat 800 people, while the Dissenting churches of the town had seating for a further 2000 inhabitants.

This increase in population, which by 1851 had risen to 15,883, caused problems in the use of the churchyard, which until the mid -1800’s was surrounded by insanitary cottages in Saint Mary Street and Little Saint Mary Street, which backed onto it Apart from the small burial grounds attached to the Dissenting churches, and the Quakers’ Burial Ground in Ropers Lane (now Albert Street), Saint Mary’s was the only burial ground in Bridgwater until the erection of Holy Trinity and Saint John’s Churches in 1839 and 1845 respectively. Bridgwater was notorious for outbreaks of various and often fatal fevers, mostly caused by the inadequate water supply. There were usually around 300 burials a year in the churchyard, which had space for no more than 100, so it was the practice to disinter bodies after about six months of burial and store the remains in the charnel house under the north transept. Newspaper reports in 1849 commented about parts of half-decomposed bodies being left for children and dogs to play with when graves were opened for new burials, and the churchyard was closed in 1851.

It is clear that changes had been made to the internal layout of Saint Mary’s, for early in the nineteenth century the organ had been moved from above the chancel screen to the West Gallery against the tower wall, where it covered the upper part of the arch.

In June 1831 a correspondent wrote to the local newspaper about the need to build a new church in the town to cater for the increased population. In May 1832 the Corporation decided to build another gallery in the church for charity school children. The Vestry agreed to apply for a faculty, but nothing seems to have been done, since in December 1833 a meeting convened to go into the question found it would be more sensible instead to build a new church. This was the origin of Holy Trinity Church, which was opened in 1839 just outside the site of the South Gate of the town at the beginning of Taunton Road. A new church, consecrated to the Holy Trinity, was built in Hamp in I960 after the demolition of the old structure in 1958.

The First Victorian Reordering

Little is known about Saint Mary’s in the early years of Victoria’s reign, as no local newspapers were published between 1834 and 1846, and information about the church building was rarely recorded in the vestry minutes. In the latter year concern began to be expressed about the state of the fabric of the church. Some of the stucco on the external walls was flaking away and there was a major leak in the chancel roof. The repairs were carried out by a local jobbing builder and this caused some criticism in the pages of the The Builder. The writer urged the removal of the galleries and the re-pewing of the church. He also commented there was a need to employ a professional architect.

Concern was also expressed about the church choir. This sang from the West Gallery and appears to have been entirely mixed adult singers, possibly using wind and string instrumental accompaniment as well as the organ.

In August 1848 the Vestry discussed the bill of Mr Hutchins, the local builder who had carried out repairs. He had claimed over £50 to supervise work worth only £180 and was accused of sharp practice. The dispute reached the pages of The Builder.

A fund had been set up to restore the organ, and in October 1848 it was decided to rebuild it. In November 1848 the Rev T. G. James was inducted in succession to the Rev D. Nihill and from this time the restoration received a much greater impetus. James had been educated at Oxford at the time when the Oxford Movement arose

The first project done was to strip the pulpit of layers of old paint and then varnish it. By April 1849 designs for the improvements to the church were advertised for, and by the end of the month the organ had been taken down and the choir was moved to the chancel. The galleries at the west end were taken down and room for the organ was to be made in the north chancel chapel by taking down the gallery there. These changes were criticised by the Corporation who in fact owned the Chancel and who complained about interference with their property.

Nine sets of drawings were received from competitors and the winner was W. H. Brakspear (1818-1898). He had worked with Pugin in designing the decoration of the Houses of Parliament Brakspear’s drawings for Saint Mary’s restoration may be seen in the Library of the Royal Institute of British Architects, London

The Organ was re-opened with a full cathedral service on 22 July 1849. There were eight choristers in surplices and bands, the first time they were worn.

It is very curious how little the changes were recorded in the Vestry Minutes, and indeed the lack of any record of faculties is astonishing – the only one recorded relating to the removal of a gallery in one of the chapels. Very little discussion appeared in the local newspapers either, but the Bridgwater Times printed in October 1849 a very interesting letter about the impact of these first alterations:

I don’t like the going on in our old church I’d as sooner sit in a barn as there just now. I used to have a cosy comfortable seat, where as sure as Sunday came I used to go without let or hindrance and where I looked round and saw lots of neighbours met together for public worship in decent and respectable order, and now I cannot find a place for myself or see where my old neighbours are poked to but am poked about on some ricketty stool jostling against nobody knows who in a most uncomfortable manner. My trouble don’t end here These men who are bitten with what they call ‘church restoring’ first pull down a thing and then put it up somewhere else and call it an improvement and that’s what they’ve done with the organ. Our old organ which used to look so well and so grand in the western gallery is taken away to expose a dissightly arch and to let in cold air from the belfiy, which it does to a frightful extent, and is carried and put up in the chancel to form a dissight there in the place of a gallery which was taken down because it was dissightly, as if one was worse than the other, and there now stands the old organ dressed up m a scanty red petticoat as if attired to be seen and as if it had no business there, which I am sure it hasn’t.

I went to church last Sunday morning, and never did I feel more melancholy, there was his worship and the corporation shivering away in a new place they’ve found for them, and the old pulpit and reading desk were torn away from the place where the’ve stood for the last three or four hundred Years, and put up divorced from each other by the pillars where the corporation seats used to be and the clerk’s desk stuck up in the centre, for no use whatever, for our new vicar won’t have a clerk, but sticks him away out of sight and makes the singing boys in white surplices do the clerk’s work. As for reading the prayers that’s now out of the question, they are drawed out in one tone, chanting they call it and the responses are squeaked out by the boys. I used to like to answer for myself in the proper form following the clerk, but now I am stared at and put out by the singing and I don’t like it I don’t see why because our new Vicar likes singing instead of praying that I should be forced to sing too. I’ve said my prayers decently and reverently in our old church for many a year long before our vicar was thought of, and I don’t see why these new fangled notions should be forced upon us by any body. Again, the nearest door for me to enter the church is the chancel door, and I have always, with hundreds of other folk gone in by that door, and now its always locked and when I asked somebody why this was “Oh” said this disciple of the vicar, that’s the priest’s door – it is kept sacred. A pretty thing this, indeed, as if every portion of the church was not as sacred as this. …

During the summer Chilton Trinity church was re-pewed and in December 1849 estimates were sought for the re-seating of Saint Mary’s. It was awarded to Mr Wainwright of Bridgwater at a price of £416. This work was commented on in The Builder. The box pews were removed and replaced by the present benches. According to Brakspear’s drawings almost 1400 seats were provided, an increase of 600 over the numbers recorded in Bowen’s report of 1830.

In January 1850 the lath and plaster vestry in the Chancel had been pulled down, the picture was moved and the church was reported to be very cold. The last gallery in the church, that in the south chancel chapel was taken down in February. At the Easter vestry there were complaints that the new pews were not as comfortable as the old ones had been.

In April it was discovered that the structure of the church was unsafe and a town rate was to be raised to pay for the restoration. Brakspear’s report was printed in full in the Bridgwater Times. He found that the walls of the south aisle were weakened and unsafe, and that the weight of the nave roof was pushing out the clerestory walls above the arches. There were also several defects in the walls of the South porch. The timbers of the nave roof were in the main sound, but the rotting away of the ends of many of them made the structure unsafe. The floors within the tower were also dangerous.

Saint Mary’s was closed whilst the repairs were done and services were held at Chilton Trinity and also Holy Trinity.

The nave roof was removed and the clerestory and eastern gable walls were taken down and rebuilt. The nave roof timbers were re-fashioned from the timbers of the old roof. Then the walls of the south aisle and porch were taken down and rebuilt to a slightly different design, in that the oriel window was not retained.

A bazaar was held to raise funds towards the cost of restoration. At the very end of the year the Wardens refused to pay Mr James and Brakspear the money for roof repairs. This was because tiles had been used instead of the slates specified. Brakspear also made another report on the state of the tower recommending the entire structure be demolished and a new one built This was rejected.

In February 1851 the Corporation voted £200 to beautify the chancel. At the Easter vestry there was complaint about the form the services were now taking.

By July 1851 work was now being done on the north side of the church. The Corporaton were sued by a local upholsterer for payment for work done in relation to the move of the corporation pews to the South transept. The Corporation lost the case.

The restoration of the church was criticised by a speaker at the Bristol meeting of the Archaeological Institute. The Builder commented on this. The Bridgwater newspaper printed a letter complaining about errors in the accounts of the restoration. In October the Diocesan Society (which had provided a grant) approved the new seating plan for Saint Mary’s.

Saint Mary’s was finally reopened on Easter Sunday 1852, with what the newspaper claimed to be a congregation of about 1500 people, though unless numbers of them stood it is hard to see where they might have fitted. By August the organ had given out and the instrument was taken to Bath for repair. Mr Akerman, the local organ tuner wrote to the paper a letter about the various moves of the organ and the clearly disorganised way the rebuilding had been done.

Permit me through the medium of your Journal to reply to some remarks lately made in it respecting the “Position, &c.” of the Saint Mary’s Organ, lest I should be accountable for the seeming failure of its remaining in proper order; as it may not be generally known that the architect’s plan limited me to the eighth of an inch. I utterly disapproved of its position and premature erection at which my employer told me “that is my business not yours” I encountered the work in the depth of Winter with outer walls down and the inner ones streaming with wet, amidst the confusion of masons, carpenters, glaziers and other work, two services a day, bell tolling marriages &c, &c notwithstanding that I had specified for the usual cleanliness and quiet

Being much driven for time for the opening I engaged an assistant (Mr Clarke, of Bath who had worked for me before; made the necessary repairs and alterations as heard at the organ opening, for £[copy blurred] including the removal to and from the vestry which had been well waterlogged. My work had not long been completed when the instrument was beset, over, under and on all sides with bricks, dust, mortar, damp and rain. I have frequently removed from within the pipes, channels, &c, a wheelbarrow full of rubbish to even .make it playable for Sundays. I subjected myself to these annoyances and losses expecting fair play when the church was in a fit state to receive an organ. Therefore, in order to show that I am not much enriched by the “Very large expenditure” alluded to in your previous quotations, I trouble you to give this a place in your impartial columns.

In November 1852 the vestry discussed the tower and spire problem again. The matter trundled on through 1853, but eventually no action was taken on Brakspear’s scheme. Instead Mr Hutchins was contracted to make repairs to the structure. In May 1853 Gabriel Poole, who had been the treasurer of the restoration fund, resigned, claiming that money spent by the Vicar had not gone through proper accounting channels.

An unseemly row, including much bad language, occurred in the church in November 1853, when Mr Haviland, one of the wardens, attempted to rehang the picture at the high altar. The other three wardens opposed the work, and in the resulting fracas they threatened to turn Haviland’s workmen off their ladders. Eventually one of them shut off the gas at the mains and ran away with the key of the stop cock, so preventing any more work, since the church was in darkness. Archdeacon Denison made a visitation a week later to sort the matter out, and during it heard evidence about the parlous state of Saint Mary’s finances caused by the restoration work.

In an effort to raise more money to clear the restoration debt an exhibition of arts and manufactures was held in the Town Hall in August 1854, and during it more than 12,500 visitors came plus an unknown number of season ticket holders.

Brakspear wrote to the Bridgwater Times in December about the of restoration, and complaining he had not been paid after almost six years work. Mr James wrote saying he suggested putting Brakspear’s bill to arbitration. Brakspear wrote again in May 1855 and in June the Newspaper printed a long article ”Architects charges and Bridgwater Church”, based on a piece in The Builder where it reported that Brakspear’s bill had been taxed by the President of the Royal of British Architects and found excessive. It is not yet clear what the outcome was. As well as his work on the church other commissions Brakspear undertook in the town were the design of the mortuary Chapel in Wembdon Road Cemetery, the design of the Vicarage in Durleigh Road and the design of the Mayoral chair in the Town Hall.

A correspondent to the Bridgwater Times complained about the appearance of the new vestry, saying it looked like a blancmange. In a later letter Brakspear noted that in fact he had never designed this, since the churchwardens had taken a rough sketch he had made and had built it without ornamentation or further discussion with him.

In January 1856 the vicar announced he was planning to preach to the Mayor and Corporation on the need for more funds to complete the restoration, but they declined to attend. A meeting organised by the expenditors – the equivalent to the present-day finance committee – ended in uproar, with accusations against the churchwardens of bullying some of the congregation for more money. The ostensible reason for the meeting was to discuss unauthorised expenditure on further decoration of the chancel. In June an amateur concert was held to raise funds, and in July poor Mr Akerman placed an advertisement requesting payment for his efforts on the organ.

Mr James resigned in April 1857 and was replaced by the Rev M. F. Sadler. During this year a series of letters appeared in the press about Mr James and the collecting box in the church for the restoration fund, accusing him of diverting the money for his own purposes. No accounts had ever been published. The affair was referred to the Bishop and the Archdeacon.

From this time the affair of Saint Mary’s church and its restoration largely faded from the newspapers for almost twenty years.

The rebuilding of the church resulted in very cramped conditions, with pews reaching pretty well to the chancel step, so it was impossible to go to the north aisle and transept without crouching in front of the base of the pulpit. A gallery was even planned for the tower, and another at the west end of the north aisle. It is not known if these were ever built Pews were crammed into the north chancel chapel surrounding the organ console, in the south chancel chapel, in the north aisle transept and above the north porch. The font was placed adjacent to the north porch, and a baptistry constructed there. The heating was to be by a Gurney stove in the middle of the nave.

The screen of the Corporation Pews was removed to the South. Transept Surplus carved panels from it were made into a sideboard which during the 1930’s was taken apart and the carvings then incorporated in the sanctuary of Moorland (Northmoor Green) Church – whose vicar had once been a curate at Saint Mary’s. At the same time there was an exchange of offertory dishes between the two churches.

The medieval chancel screen was dismantled and rebuilt separating the choir stalls from the north and south chapels. There were no screens separating the chapels from the nave.

In the sanctuary, the altar was placed on steps about three feet higher than the chancel floor and was backed by a carved reredos reaching to below the bottom of the picture. The picture was placed against the east window, which was not covered, so that the tracery showed, and on either side of it were fixed ornate moulded frames containing the text of the Ten Commandments. A painted text followed the curves of the window arch. The walls in the sanctuary were tiled to about waist height.

It is not known whether the altar at Saint Mary’s at this time was furnished with a cross and candlesticks. To many eyes these favoured Popery, and during the 1850’s there were notorious court cases instigated to prevent their use. As late as the 1870’s riots broke out at Moorland Church (Northmoor Green), when the vicar, Mr Hunt attempted to introduce a cross to the church.

This layout was clearly planned for services held at the area of the chancel step where were located the pulpit, lectern and reading desk. The high altar was invisible to the bulk of the seats, and in the days before public address systems the ceremonies there would be largely inaudible. One wonders how audible were the words spoken at the chancel step, and just how much the congregation got out of the service. The frequency of communion services then is not known, nor the numbers who attended.

These changes did not find favour everywhere. In many towns they were greeted with suspicion, and today we have little idea how they were regarded.

A poem which appeared in a Bridgwater newspapers gives an idea of how the changes were perceived in some quarters:

Complaint of the old Parish Clerk against ritualism

Our Parson’s took up with Ritchelist views,

And he’s all over changed from his hat to his shoes;

His coat is so long, and his face is so grave.

And he calls his good crab stick a pastoral stave;

And his voice has got hollow, and sad-like, and mild,

And he’d think he was yielding to sin if he smiled:

They may say what they please, but whatever they says.

I don’t like the looks of them Ritchelist ways!

Our Parson, he once was so hearty and stout.

And knew that the farmers and folk were about:

He’d talk with the men as they worked in the field,

He knew every acre and what it would yield;

He’d a famous loud voice, and a kind, merry face,

‘Cept when he was scolding a child in disgrace;

Now he walks through the lanes in a sort of a maze,

And that’s what has come of his Ritchelist ways!

And the old village church, he’ve adone it up new

And there’s plenty of benches but never a pew:

And pillards, and Aalters and things queer in spellin’.

And as to the vestry, that’s quite past my tellin’.

There used to be two gowns I had in my care,

A black one for preaching, a white un for prayers;

And now there are twenty, with gold all ablaze,

And that’s the expense of these Ritchelist ways!

There’s tippets and stoles, that is always in wear

And copes to put on for the Litany prayer

And green with white edgings for Churchings – and listen!

He puts on a purple and white gown to christen!

There’s things that hang loose and things that fit tight,

And he’s mighty displeased if I don’t bring ’em right.

Oh, its almost enough a poor body to craze,

The ins and the outs of these Ritchelist ways!

Then there’s bowings and scrapings and turnings and flexions,

It’s hard work to mind ail the proper directions:

He’l first chant a sentence, then turn round his stole,

Then wheel to the East with a sort of a roll;

Now he reads low and loud – now he jabbers so fast,

As if it was something he wished to get past;

At the back of the building you can’t hear a phrase,

For they don’t speak distinct in these Ritchelist ways.

And the music, it’s altered, I can’t tell you how,

But the old Psalms o’ David we never sing now;

They’ve got some new Hymns, with some very queer words,

And they twitter and pipe like a parcel of birds;

They tell me it’s grand, and I shouldn’t complain,

But I long for the old Psalms o’ David again,

Or else for our godly and Protestant lays –

Not these dreadful quick chants of these Ritchelist ways.

I’ve been Parish Clerk for nigh thirty year.

But the Parson and Wardens is getting so queer,

An’ the work of my office is getting so great.

What W’i brushing the vestments and cleaning the plate.

That I’d almost resolved to resign it and go,

But my friends, they say “Don’t,” and my wife, she says “No.”

So I bide in my place, and each Sunday I prays

There may soon be an end to them Ritchelist ways!

Bridgwater Mercury 8 October 1873. This was originally written by Ebenezer Higgins and published in Cheltenham in 1867.

The Second Victorian Restoration

In the 1860’s there was correspondence in the newspapers about the state of the choir, with several writers complaining about being excluded from taking any part in the services since all the responses were sung and they were made to feel interlopers if they attempted to join in. One correspondent complained about “bawling boys in shirts”.

At the end of the 1860’s letters appeared about the lack of heating and draughts through the main doors, which were evidently opened fully when the church was in use. Wicket doors were cut in them to cut down on the draughts entering the church. There was also lengthy discussion of the organ, which was almost unplayable since parts of the pipes were so rotten the metal could not support its own weight. In 1871 a new ‘Father Willis’ organ was placed in the church, which is the basis of the one used today. In 1872 and 1873 there was much discussion by the Corporation about the clock and chimes in the tower. The chimes were of the barrel organ type which played the bells every three hours. The mechanism for this may still be seen in one of the upper floors of the tower.

During 1876 repairs were done in the Chancel. In 1877 a fund was started to replace the glass in the windows in the west end of the church, and there was some discussion by the Corporation about whether they should sell the picture. The main gates to the church from Little Saint Mary Street, which had been opposite the end of Silver Street, were moved to their present position. At about this time the last of the cottages which backed onto the churchyard from Little Saint Mary Street were demolished. There was also discussion by the Corporation on making alterations to the chancel including a new floor. At the end of 1877 a comprehensive scheme of improvement was agreed. This widened the side aisles at the front of the church and the centre aisle for its entire length by cutting back the ends of the pews and replaced the lias tomb slabs with encaustic tiles. A hot water-heating system and brass standard gas lamps were installed. The church was closed throughout February 1878, and services were held in the Town Hall. Red tiles were fixed to the walls of the nave and transepts up to the stone dado. As the work progressed some pews were removed to open up more space. The church re-opened 29 July 1878, but fund raising continued throughout 1879. A water-powered organ blower was installed early in the 1880’s, soon after the opening of the Bridgwater Corporation Waterworks. To judge by the number of late Victorian memorial slabs within the church, the last decades of the century must have been very prosperous for Bridgwater, but apart from the donation of the brass eagle lectern, little evidence has been found about major fabric alterations then.

The 1930s Simplification

The trend of the whole of the twentieth century has been a continual progression towards simplification of the church fabric and the removal of ornamentation. Around the turn of the century the font was moved to stand by the door from the nave to the bottom of the tower, with a new marble plinth. At about the same time the vestry was demolished and rebuilt to an enlarged plan to include a sacristy. The gas lighting system was replaced by electric light in 1902. Screens were built dividing the north and south aisle chapels from the nave. The pews were removed from the south chancel chapel in the early 1920’s when it was converted into a memorial chapel for the dead of World War I.

In 1937-8 the ornamentation at the east wall of the chancel was removed, as were the wall tiles of the sanctuary and a new altar rail fitted up. The sanctuary pavement was lowered and the picture raised slightly, thus bringing it into much more prominence from the nave of the church, compared with the altar. A credence-table was made from a fragment of CI3 woodwork which had once been in the church and relegated to Wembdon Road Cemetery chapel. A Persian rug was placed on the pavement before the Altar. The tiling of the walls of the aisles and transepts was removed and the pale colour-washed plaster substituted. The rubble-stone wall of the Tower end of the Nave and the inside of the North Transept were all plastered and similarly colour-washed. At about the same time storage cupboards for altar frontals were built against the west wall of the north aisle. Internal doors were fitted between the north aisle and the baptistry, to stop draughts.

After the Great Simplication of St Mary’s came World War 2.

From the 1960’s liturgical changes with Series I and 2 and later Rites A and B meant radical changes to the role of the Eucharist, or Parish Communion, which in turn made the introduction of nave altars very common in churches, where the ceremonies could be more readily seen by the congregation.

In 1967 two rows of pews were removed from the front of the nave. This allowed better access around the pulpit, the reading desk and into the Memorial chapel. In 1973 a short-lived experiment was made at using a second altar on the lower step of the chancel, but this does not seem to have been properly thought through, since no altar rail was provided and the project was abandoned after about six months. In 1976 all the pews from the north transept were removed and the space fitted up for socialising, in memory of Revd. Carl Swan who had been vicar. A proper ringing chamber was made in the tower in 1980 by inserting a new floor and glazing the arch to the church. A major electrical re-wiring of the church was done. Also in 1980 a major exhibition was held in the church on its history and also to show visitors something of the life of Saint Mary’s today. An additional pair were added to the choir stalls above the double chancel step, using original pews salvaged from the North Parvise. In 1989 the vestry was remodelled with better storage and improved toilets. In 1992 the Benefice office was installed in the ground floor of the tower.

The 2016-2017 Reordering

Back in the late 1990s thinking revolved around making more space in the church by building an internal gallery at the west end, which could have seating at an upper level and offices and storage below it. There was no thought about removing all the pews.

Following a Vision Conference in 2002, attention was given to making the church more welcoming to strangers, by rebuilding the vestry to make it bigger and to make a visual impact on visitors from the Fore Street direction. Various options were considered, including a timber-frame structure with access directly into the Swan Transept. There was the disappointment of having the Diocesan Advisory Committee change its advice about what was needed, perhaps reflecting later changes in the make-up of that committee. There was hostility from the Victorian Society to the demolition of the Edwardian vestry, as well as doubts from the District Council’s planning committee and the Bridgwater and District Civic Society.

There was a change of architect and thoughts of rebuilding the vestry were abandoned around 2009. Instead, schemes for removing the pews were discussed exhaustively and adopted. At the request of English Heritage an academic study of the significance of St Mary’s woodwork had been undertaken and published internally in 2007. This formed the basis of a case-study in a book about the history of church seating. Trevor Cooper & Sarah Brown, (eds), Pews, Benches and Chairs: Church Seating in English Parish Churches from the Fourteenth Century to the Present (2011) Another study was done later for the architect about the Charnel house under the north transept.

A great deal of effort went on behind the scenes to move the project on. Much effort went into resolving the funding needed. There were a number of field-trips to inspect other re-ordered churches and to see alternative seating. Following the fuss about the significance of the Victorian pews, some blocks were retained, but with the compromise of being made mobile, so giving infinite flexibility in how they might be used, and showing visitors how they looked.

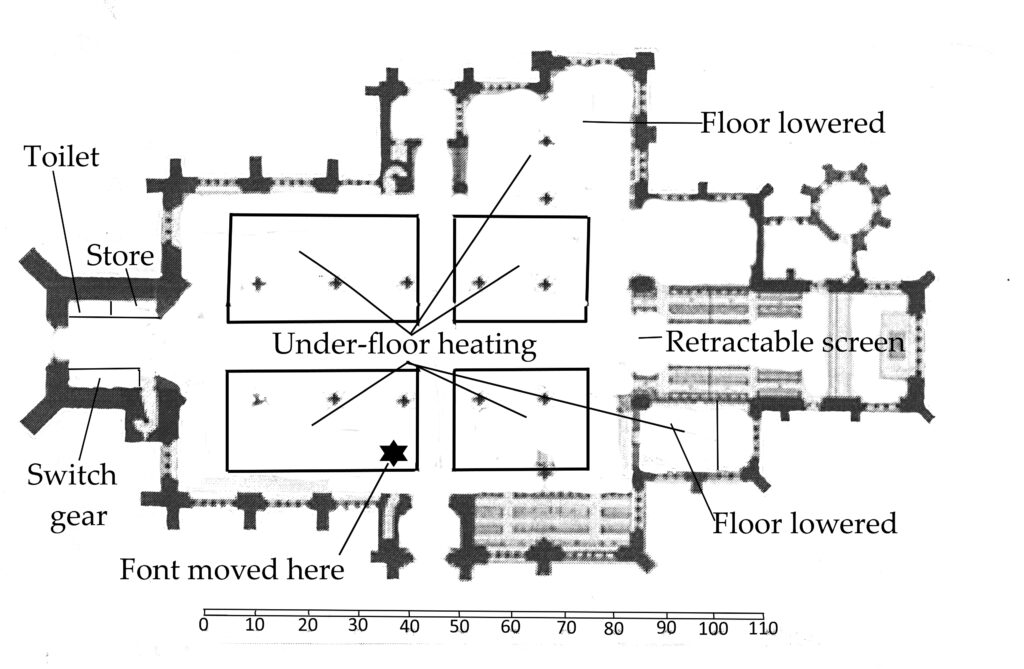

The floors of the north transept and St George’s chapel were lowered to the same level as the nave and aisles, making them readily accessible to wheelchair users. The font was moved from by the west (ceremonial) door to by the south door, which is is now the main entrance. The timbers of the nave roof were all cleaned of the black varnish of the Victorians, and looks stunningly beautiful with the new lighting. The lighting has modern energy saving LED bulbs in a series of coronas suspended from the the apices of the nave arches, which project the light both upwards and downwards.

The parish office was moved from the bottom of the tower to the vestry, and a toilet for the disabled with baby changing facilities placed there, as were the switch gear for the new electrical installation, and cupboards for the choir’s robes and music.

The sound system is state of the art. The underfloor heating is a great boon, as is the projection screen which can be readily hidden when not in use.

More can be read here at the website of Ellis & Co. contractors on the project.

How it came to be: Pictures from before the Reordering

MKP, c.2014

How it came to be: Pictures from after the Reordering

MKP 2018