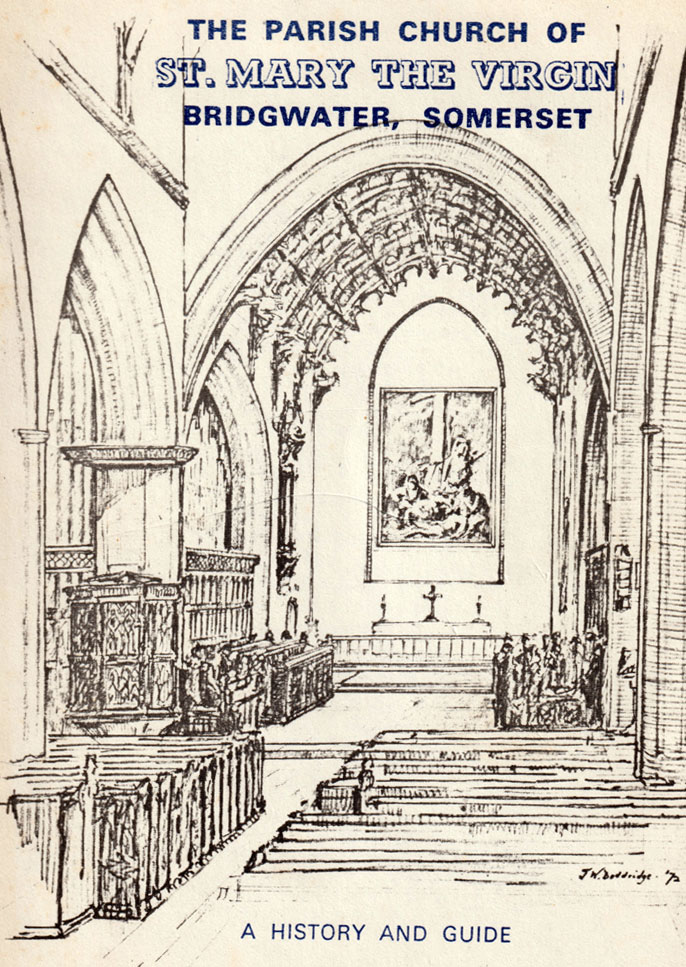

The Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin Bridgwater, Somerset: A History and Guide. By John F. Lawrence.

John ‘Jack’ Lawrence (1907-1996) moved to Bridgwater from Yorkshire in 1930 to take up a teaching post at Dr Morgan’s School. He became an expert on the history of Bridgwater, which was ultimately expressed in his posthumous History of Bridgwater (2005), completed by his son Chris. This guide to St Mary’s Church was probably completed in 1972, although the printed edition this copy was taken from dates to about 1977.

ST. MARY’S – BRIDGWATER: THE STORY OF AN HISTORIC CHURCH

By JOHN F. LAWRENCE, M.A., M.Litt.

St. Mary’s church is the most historic building in the town and its size bears witness to the importance of medieval Bridgwater.

The Spire

The spire is a notable landmark which can be seen for miles. It was added to the tower in 1367. Its construction was no mean feat for the builders of that date. It is the work of one Nicholas Waleys, i.e. the Welshman, of Bristol. We still have the accounts, meticulously kept, from which we learn that it took a year to build the spire at a cost of £143 13s. 50. Much restoration has been done in later days but the appearance of the spire is very much the same as it was in 1368. There are very few spires at all in this part of England and the great height of the Bridgwater spire compared with the height of the tower makes it all the more unusual. The tower is 60 feet high and the spire 114 feet.

The Fabric

Down to 1850 the church was covered with a rendering of plaster, as were most churches. Modern taste has required its removal in order to expose the natural surface of the stone. We now see the red sandstone of Wembdon and the blue lies which was brought down the river from Pibsbury, near Langport, as well as the golden oolite from Ham Hill which was always visible in windows and doorways.

The Tower

The oldest part of the building is the tower. Pevsner thinks it is 14th century because it has Decorated windows. But its proportions are too squat. The tower arch, inside, is much lower than the arches of the nave, so that it does not fit into the 14th century design. It must have belonged to a smaller 13th century church, traces of which can be found. Two stone corbels with carved heads have been left stranded, one inside the north aisle and the other round the corner in the north transept. The 15th century west door has a drip-stone with a fox-and-goose finial on the left-hand side. Inside the tower another narrow 15th century door gives access to the stair. It is still possible to climb out and look over the roof tops just as Monmouth did on the eve of Sedgemoor. The massive diagonal buttresses were probably added after the construction of the spire.

The Exterior

The windows of the south aisle may be straightforward replacements of 14th century ones. The south porch, however. is plainly Victorian. The Decorated window on the right of the porch may look genuine but it is a 19th century concoction replacing a 16th century square-headed window which was set in a projecting bay. Other Victorian work can be identified from the use of a very white stone, probably Bath stone, on the exterior, instead of Ham stone. This test alone condemns much work on the north side as not genuine, including the Early English window in the north transept. This does not apply to the crypt, now the boiler house, which must be 14th century, as are the two tombs on either side of the door. This crypt was the medieval charnel house.

The North Porch

The medieval porch had an upper story which was the clerk’s room (camera clericorum). Above was the sacring bell. Below, during the celebration of the eucharist, a clerk would hold the bell-rope whilst he watched the priest through an aperture in the wall. There is still an aperture there with wooden shutters to keep the draught out. Loaves of bread were distributed every week in the North Porch. The whole porch has been re-modelled in Victorian times. The church seems to have reached its present proportions in the 14th century. Since 1400 only the chancel chapels have been added.

The Chapels

The chantries of the Bless. Virgin Mary and of Holy Cross came into existence in the 13th century. The Lady Chapel was situated behind the high altar, occupying the space which is now the Sanctuary. The Holy Cross, or Rood, was suspended from the top of the chancel arch above the rood screen. The iron hook is still there. The altar associated with the Holy Cross, however, was in the north transept above the charnel house. The duties concerning the rood, which would involve the lighting of candles on the rood screen and the saying of masses in the side chapel, were probably performed by the parish clergy. But the Lady Chapel had its own chaplain who received £4 6s. 8d. a year for his services. Also in the north transept, next to the porch, was the chapel of St. Katherine. The 15th century saw the growth of religious guilds for which further chapels were created. The chapel of the Holy Trinity, now occupied by the organ, was built c1400 at a cost of £4. Early in the 15th century the chapel of St. George was built on the south side of the chancel. In 1920 it was restored in memory of the men who died in World War I. There were two more chapels in the south transept, now occupied by the corporation pews : All Saints and St. Ann’s. Only three of these seven chantries appear to have survived until 1548 when they were dissolved by Edward VI. They were the Blessed Virgin Mary, Holy Trinity and St. George.

A description of the church in 1842

In 1842 the Rev. J. J. Toogood, Rural Dean, paid an official visit to the church. If we consider some of the features which he observed, it will help us to understand the fundamental changes which have taken place since that date. He mentions a gallery in each transept as well as “a gallery which runs all across the western end of the church.” These wooden galleries have gone. The western gallery had been erected in 1832 “to the use of Morgan’s and all other Charity Schools in the Town … forever.” The organ was in this west gallery and “its situation cannot be improved,” he says.

“At the East end of the nave are the corporation seats” – In the early 17th century a screen was erected across the east end of the nave, so that the members of the corporation sat between two screens, facing the congregation. These were eventually thrust aside so that everybody in the nave could have a clear view of the altar-piece. Their removal made it necessary to dismantle the pulpit, which stood against the “2nd pillar from the chancel,” and to install it in its present position. During this operation we seem to have lost the Clerk’s desk, which Toogood described as “part of a fine old lectern.”

His description of the roof is very quaint : “the ceiling is of plaster : it is circular and slightly ornamental from it are dispended two brass chandeliers.” Evidently this was the normal type of Somerset waggon roof (cf. Isle Abbotts). During the changes which were made to the roof, we lost the two chandeliers These were undoubtedly objects of great beauty, made in Bridgwater by Bailey, the bell-founder. Some of our village churches still have Bailey chandeliers. The nearest is at Kingston St. Mary.

Victorian Rebuilding

In 1850 the Parish Vestry embarked on an astonishing scheme of alterations which has given us the church as we see it today. They began by offering a prize for the best plans. They chose W. H. Brakspeare as their architect and employed Hutchings, a well-known local builder to do most of the work. In 1852 they completely re-built the roof of the chancel, changing it from a waggon roof into a pointed-arched roof. Only the bosses of the medieval roof were retained. These were carved c 1420, for one of them is inscribed with the name of William Patehull who was Master of the Hospital of St. John from 1416 to 1422. The Hospital held the patronage of the church during the pre-Reformation period. All other features of the roof—pierced stone corbels, elaborate wooden tracery, smiling angels—are Victorian. Two entirely new windows were inserted in the walls, north and south, on each side of the Sanctuary. These were obviously intended to light the altar-piece. Indeed, the Town Council had offered a grant of £200 “in aid of the chancel repair, on the express understanding that the Painting should be replaced at the East End of the church over the communion table.” Both these windows are in the true Gothic tradition but the east window was replaced by something much more ambitious which is a complete travesty of Gothic. The total cost of these elaborate changes was £600. In the nave the old roof was removed, a new clerestory constructed, and a new Victorian hammer-beam roof created. The design of this roof has a touch of genius. The Victorians also constructed the two curious balconies above the two porches and added some very peculiar cusps to the 14th century tomb recesses. However, the slender pillars of the nave with their 14th century mouldings, create a genuine medieval atmosphere which pervades the whole building.

The Bells

The Borough Archives contain an interesting account of the founding of a bell at an early date c 1314. The effort was begun with a salvage drive to collect scrap metal. No medieval bell has survived. The oldest bells in the peal were made by a local firm, Bailey of Bridgwater, in the 18th century. The heaviest bell has an inscription : “From lightning and tempest good Lord deliver us.” Church bells were rung at the height of a storm in the belief that this would protect the surrounding houses from being struck by lightning.

Woodwork

St. Mary’s is famous for the excellence of its woodwork. The original 15th century roof can be seen in the south transept where there is it huge boss carved with a figure of a king, crowned and seated on his throne. Although it has been restored, the pulpit is late 15th century work. In the chancel there are three misericord seats carved c 1500, obviously by the same carver who made the medieval parclose screens for the Trinity chapel. Parts of the original work can be found round the organ. The most delightful example of the woodcarver’s art is the Jacobean screen which now graces the corporation pews in the south transept. It consists of a series of classical arches supported by slender pillars, each of which displays a wealth of detail. The communion table is of somewhat earlier date, probably Elizabethan.

The Altar-Piece

We have seen how the church was practically re-designed after 1850 so that the huge painting, Descent from the Cross, which covers the east window, should dominate the church. We know that this picture was bought in Plymouth by the Hon. Anne Poulett at a sale of naval prizes. Presumably it had been taken from a French or a Spanish privateer during the American War of Independence. The capture might well have been made in the Mediterranean. It is a minor master-piece by an unknown artist. The latest theory is that it was the work of Ludovico Stern, a German artist who worked in Rome in the late 18th century. Before he died in 1785, Mr. Poulett presented the painting to the town. From 1768 until his death he had been a Member of Parliament for Bridgwater.

Miscellaneous Church Furnishings

A pyx cover, a very fine piece of 14th century woodcarving, stands in the chancel. The pyx was a vessel in which the consecrated bread was kept. The octagonal font has quatrefoil panels of c 1500. It is still in use and is the same in which Robert Blake was baptised. A broken font of earlier date was recovered from the churchyard and is now preserved in the north porch. A royal achievement of Queen Anne’s reign hangs on the west wall. On the north wall of the chancel is a memorial to Francis Kingsmill who died in 1620. He is shown wearing armour and reclining on one elbow.

In the Churchyard

The circular stone which lies on the grass near the east gate, is a portion of the base of Pig Cross, a simple market cross which stood in Penel Orlieu. The table-tomb of late 17th century date is the tomb of the Oldmixon family. However, John Oldmixon the historian, who lived here in the early 18th century, died in London and was buried there.

The Organs

The earliest mention of an organ in the church was in 1448, when it was recorded that the churchwardens paid 18s. 3d. for “ij bilewes pro les organes.” [2 bellows for the organes]. It is known that Richard Chappington of Exeter did some work on an organ in the late 16th century. The Chappington family were important organ builders in the 16th century, and did work at Exeter, Bristol and Salisbury. Richard died in 1619. Apart from this, and the fact that the instrument preceding the present one stood on a gallery across the west end of the nave, there is no information available about any organ prior to 1871.

On August 17th 1869 there was a meeting of all those that held sittings in the church, at which it was unanimously decided to start a fund for the Provision of a new organ. A committee, which included amongst its members, Charles Lavington the organist, was formed to raise the necessary money. It was just at the time when Henry Willis was at the height of his fame, through his reputation as builder of the organ in the Royal Albert Hall. A few years earlier he had completed the organ in Wells Cathedral. It was to Henry Willis that the committee entrusted the building of their new organ, which was completed at a cost of £800, and formally opened on Thursday, 21st September, 1871. The day was one of great festivity, for, in addition to two choral Services there was a public luncheon and a recital by the famous George Riseley. Unfortunately the records of the firm of Willis. which included the original specification, were destroyed in 1942, so it is only by conjecture that we can reach a conclusion as to its composition. It is known that in 1879 Willis was paid to add a Vox Humana stop and a tremulant. After what seems to have been some disagreement between Willis and the church authorities over this, the care of the organ passed into the hands of Vowles of Bristol. The organ was completely rebuilt by Vowles in 1922 and the opening recital was given by Ralph Morgan on Thursday, February 8th 1923. The whole organ was thoroughly cleaned and overhauled, and the old mechanical action was replaced by what was then the latest type of pressure pneumatic action. The choir organ was enclosed in a box, and the stops placed at an angle of 45 degrees to the keyboards. An electric blowing plant was installed and the total cost was just over £1,000.

The work done by Vowles in 1922 was always considered unsatisfactory, as only 16 years later, it was found necessary to overhaul the instrument once again. On this occasion, the work was entrusted once more to Willis but owing to finance this could only have been in the nature of ‘first aid’, but a new pedal board and two new balanced swell pedals were installed. Since 1938 the mechanism of the organ had been steadily deteriorating until, in the early 1960s, it was at times almost impossible to play upon it during prolonged periods of very dry weather. By this time a fund had been started for a further restoration which in 1964 received a generous legacy from the late W. R. Thomas. The rebuilding was entrusted to the firm of Percy Daniel Et Co. and was re-dedicated by the Lord Bishop of Bath and Wells on Sunday, 20th March 1966. The opening recital was given by Dr. Herbert Sumsion on Saturday, 18th June. At this restoration, which was in many ways the most comprehensive in the history of this fine instrument, the builders and church authorities agreed that, as far as possible, the original Willis characteristics should be faithfully preserved. The old organ contained two double rise wind reservoirs, one each for high and low pressure reeds. Now, the Great, Swell, Choir and Pedal Organs, together with the high pressure reeds and action are each provided with Separate single rise sprung chests. New electro-pneumatic action has been installed throughout, with a modern drawstop console complete with piston setter board. All pipes have been fitted with new tinned steel tuning slides where required, and the tonal changes that have been made are such as will allow the instrument to be much more resourceful than it ever was before. The scheme of the organ was drawn up by Mr. W. Gulvin, the managing director of Percy Daniel & Co in consultation with the then organist of the church.

The Church Needlework.

The attention of visitors is drawn to the many beautiful examples of needlework which have been presented to the church during the past few years. These have been designed and executed by past and present members of the congregation of St. Mary’s, and are the product of hundreds of hours of patient effort. The principal works are: The five-sectioned Communion Rail kneeler with its central design of the chalice and symbols of bread and wine, with, on either side. emblems and designs signifying the saints; the seat-runners in the choir stalls, extolling the place of music in worship, together with the individual choir stall cushions, and the Communion Rail kneeler in the Lady Chapel, which is the result of three years. devoted work and contains almost half a million stitches. There are also individual seat cushions and kneelers in the Vicar’s and Curates’ stalls, and through the main body of the church there are already more than seventy new pew-runners of different designs. Other work can be seen in various footstools in the sanctuary and at the lectern, etc.